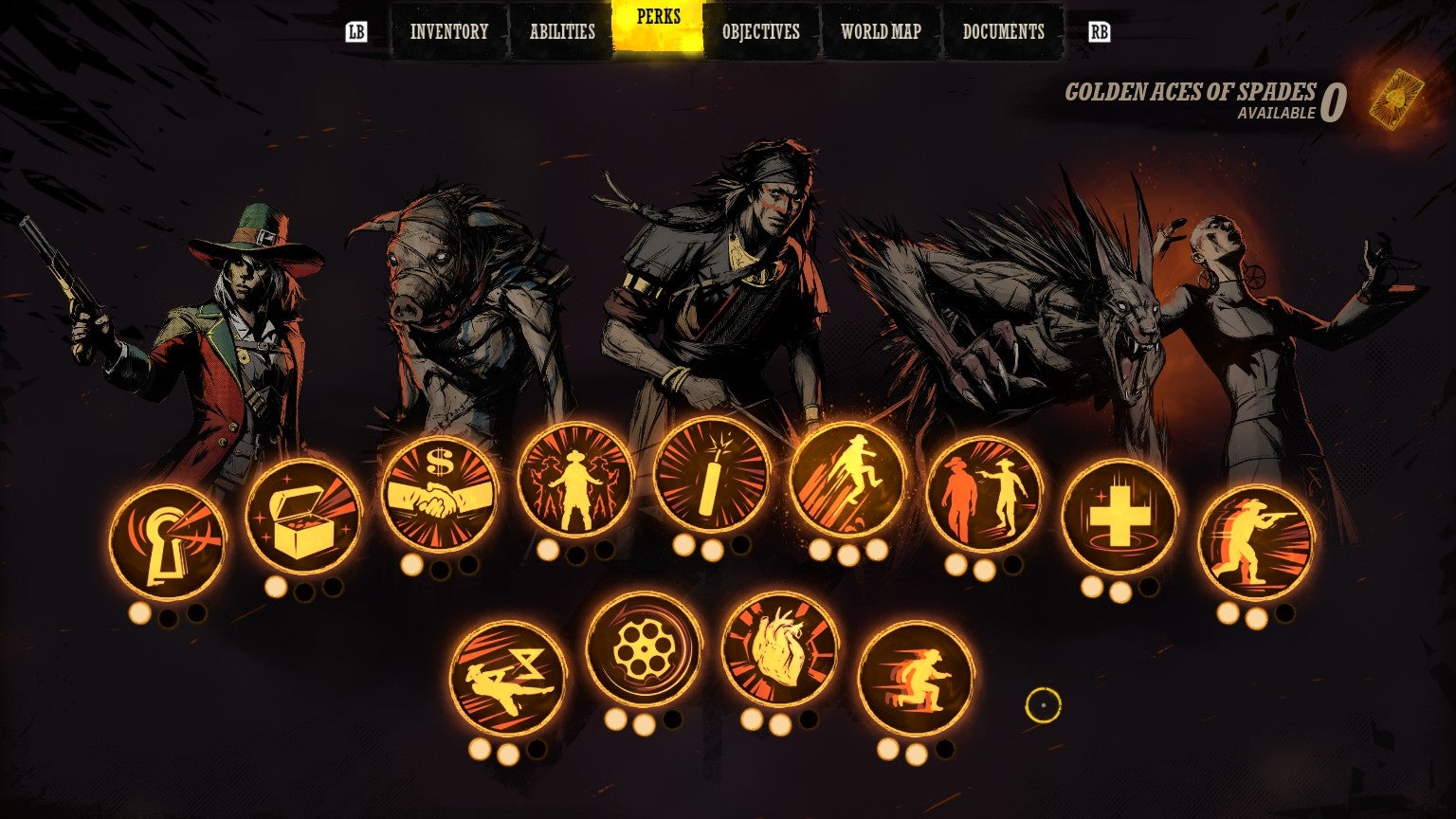

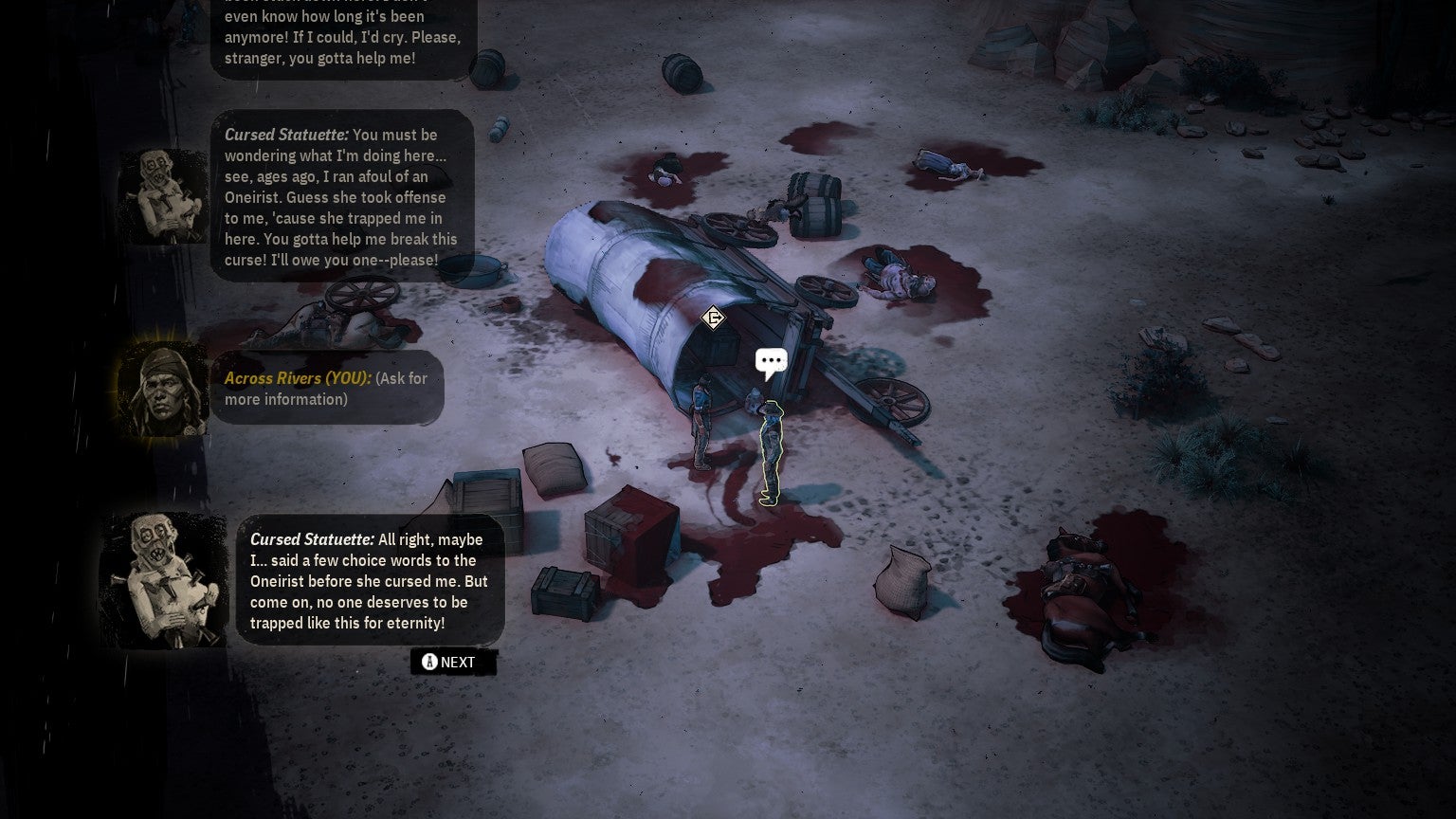

WolfEye’s Weird West mixes this vast, rancid legacy with outright fantasy elements sourced partly from the likes of Lovecraft and partly from the studio founders’ previous Dishonored games. This very much isn’t your classic rootin’ tootin’ cowboy yarn. Head out into the wilds and you’ll find raucous villages of pigmen and ghost towns that absent-mindedly manifest from the foundations up. Dip into the caves and you’ll encounter ravenous mutants and blue-stone temples where cultists debate visions of the apocalypse. Magic is an everyday concern: town deputies sling lightning and fireballs alongside bullets. Stores are happy to trade in ectoplasm and cursed goblets alongside deerskin and copper. Quests alternate gritty pulp novel conceits with otherworldly enigmas: one moment you’re squeezing a barkeep for information on a posse of kidnappers, against a backdrop of tinkling piano; the next, you’re trying to make sense of a captive meteor. The realm is divided not just between settler communities and indigenous Americans, but factions of cannibals, werewolves and witches, all of them being manipulated by an off-screen illuminati of cowled figures who might as well call themselves game designers. There’s a lot going on here, but in practice, Weird West’s weirdness is… hit-and-miss, much as its efforts to miniaturise the knock-on immersive chaos of the WolfEye founders’ previous Dishonored games are more admirable than satisfying. It’s a valiant attempt at recreating the protean intricacies of the best immersive sims with a smaller team and budget, packed with great ideas that don’t quite mesh. The best of these is body-switching. You play a member of the aforesaid cowled illuminati, who in turn plays many other characters - possessing a different person chapter by chapter care of a magical brand, in a grand, sorcerous experiment of unknown purpose. Beginning in different corners of the world map, a grimdark themepark of archetypal North American geography, each character offers not just a different playstyle but, in theory, a different perspective and set of dramatic constraints. You start off as Jane Bell, an ageing bounty hunter forced to saddle up for One Last Job after her partner is abducted by cannibals. Her story teaches you the basics of stealth - think viewcones and hiding in bushes - and gunplay - think crouch behind cover, plus a huge emphasis on AOE abilities and terrain traps - together with the bone relics and glittering golden cards you’ll use to unlock abilities and boost your stats. She also shows you the ropes of various map mechanics, like pop-up random encounters and the game’s morality system, with crimes only affecting your reputation if witnesses live to tell the tale. It all seems comprehensible enough - an Old Western Fallout-style CRPG with a touch of the Arkane. But then you’re plunged into the body of Cl’erns Qui’g, a recently transformed pigman. Qui’g has no idea who he is or rather, used to be. He’s also, to say the least, unwelcome in human towns, so selling your surplus inventory can be tricky. On the upside, he can devour corpses to replenish his health. After Qui’g comes Across Rivers, a member of the Lost Fire Nation, which are based on real-life Anishinaabe indigenous groups and written by Elizabeth LaPensée, who is of Anishinaabe descent. Across Rivers and his folk appear as protectors of the West, here to track down and purge the literal spirit of greed behind settler expansionism. Supernatural threats (and allies) aside, he has to worry about rifts with neighbouring non-indigenous trapper communities, which you might choose to heal. Fourth in line is Desidério Ríos, sharp-shooting werewolf and messiah of a quasi-evangelical religion who are searching for something called the Blood Moon. In theory, he’s the mortal adversary of the final playable character, a witch initiate called upon to suture together the pieces of the grand conspiracy fleshed out by previous episodes. The idea of seeing the same world through different eyes describes many class-based RPGs, of course. The chaser in Weird West is that characters shape the odds for their successors, each required to deal with the consequences of the previous chapter. This is most conspicuous, of course, when it comes to major narrative choices - as Jane the bounty hunter, you can erase one particular gang of outlaws from the game, making life easier but perhaps, less exciting for the rest of the cast. But it also applies to smaller stuff, like towns rinsed of life eventually refilling with stranger threats, or side objectives carrying over between characters. Previous protagonists can also join your posse as NPCs, letting you access your previous inventory. Depending on your choices and reputation, others may become your foes. It’s a fantastic ensemble premise I’d love other games to learn from. The same sense of bubbling potential applies to the level maps, each a moody Petri dish about a minute across, curling up into parchment at the edges. These range from relatively vibrant trading hubs through isolated farms and churches to festering swamp and boneyard. Beneath the surface lie mineshafts, ice-locked treasure troves and forests of glowing cave fungus. Bigger settlements harbour shops, banks, doctors, general stores, blacksmiths and tanneries, plus a story-specific building or two. Coyote and deer roam the fringes, to be hunted for life-restoring food or pelts to craft into vests, the game’s one armour item. While hardly as intricate as, say, a Hitman level, these maps reward a bit of contemplation. Their occupants follow daily cycles, locking up after dark and visiting the saloon: if you aim to rob the bank, it’s advisable to do so at night. Most maps are also primed to explode, with barrels of TNT, flammable oil or poison dumped all over, tempting your trigger finger as you crawl through the undergrowth. If Dishonored is the topline aesthetic influence on Weird West, colouring everything from the slashing inks of the character art to the singsong wispiness of the music, the game’s love of self-propagating terrain hazards recalls Divinity: Original Sin 2. Rainwater conducts electricity and extinguishes dynamite fuses. Wildfire spreads in the direction of the wind; you can lay paths for it by shooting out oil barrels and lamps. The dead are terrain variables, too. Weird West has an unabashed interest in the many applications of corpses, going beyond garden-variety tactics like hiding them from view. Each area has an entourage of vultures, descending swiftly on the fallen and sometimes blocking your shots. Most settlements have an actual, functioning graveyard: return to the scene after a gunfight and you’ll find your victims freshly interred, together with any items they were carrying. You can bury the dead yourself, which I often did while playing as the comparatively reverential Across Rivers, and the game tantalises with the thought that exposed bodies might return as zombies or something worse, though I’m not sure this ever happened during my playthrough. Bags of potential! But while there are some nice setpieces, like the aforesaid ghost town, Weird West struggles to make the most of all these possibilities. The first warning sign, perhaps, is the top-down view, which, together with the dense graphic novel art direction, often squashes and obscures the cleverness of terrain setups, while making the collection of objects an absolute nuisance. The cast feel a bit squashed too, beyond their narrative framing - each distinguished in the hands by four abilities that are both unremarkable individually and a poor basis for a playstyle, with no modifiers to unlock and a sparse selection of combo opportunities. The pigman and the witch are clearest cut: he’s a brawler with rushdown moves and an AOE stomp; she’s a kind of hacker duellist, able to teleport, absorb bullets as health, and conjure spectral clones as distractions. The others resemble everybody’s awkward first stab at a Skyrim build. Jane Bell is good at forcing people to like her for 10 seconds, or kicking them into her makeshift traps. Across Rivers can’t work out whether he’s a sniper speed-walking through the bushes or a D&D shaman conjuring up spirit bears and (enjoyably unpredictable) tornadoes. Most disappointing of all is Desidério the werewolf, who is in practice a befuddled cleric equipped with heals, buffs and team-wide invisibility spells - the actual werewolfing is a glorified melee power-up. You’ll spend more time thinking about the weapon abilities, like silenced rifleshots or electrical pistol rounds, and to a lesser extent, passive perks such as increased jump height or faster reloading. These latter options are shared across the cast, which means that characters ultimately blur into one, though you do need to unlock weapon abilities afresh in each chapter, which is an incentive to try out different tactics. I could live with some underwhelming special moves. More seriously, Weird West is unable to make the most of the different and differently constrained vantage points each character gives on the game’s landscape and society. The pigman gets a quest early on that makes you acceptable to human townsfolk, nipping the most intriguing element of his story in the bud. You can play out the whole werewolf arc without ever turning into a wolf; there’s no lunar cycle, and thus no need to worry about things getting hairy when you’re trying to (e.g.) sweet-talk the sheriff. Across Rivers eventually gains the ability to talk to roaming ghosts, but in my 30 hours with the game this was mostly the basis for additional fetchquests of the “find my favourite hat so that my soul may know peace” variety. The maps, meanwhile, are lovely dioramas, but their dinkiness means that you seldom need to seriously search for different methods of completing objectives. There’s the usual imsim spread of high or low-profile tactics - sneak through the long grass! Climb through a window or drainage vent! Set up an elaborate multikill by kicking over oil barrels! But everything feels too available, with too many options per inch of screen estate, and none of them very complex or imaginative. The game seems positively paranoid about people losing their way, at times: if there’s a locked door, it’s likely that most guards will have a key. You’ll occasionally have the option of talking your way through a situation, but this is seldom more adventurous than a single dialogue choice, which is a shame given the period swagger and compactness of Weird West’s writing. Gunplay is usually the most satisfying approach, but this is damning with faint praise, because the gunplay is 50 percent circle-strafing while spamming the game’s incongruous but dependable bullet-time dodge, and 50 percent aimless blasting in hopes that exploding oil barrels will take care of the rest. Weird West is generally a more entertaining spectacle when you hurl things at it indiscriminately, not least because the background systems have the usual immersive sim propensity for going slightly haywire. Here’s an obligatory “grenade rolled down the hill” anecdote: enemies who escape your rampage may form vendettas, in faint echo of Shadow of Mordor’s Nemesis system. At one point I was ambushed by bandits and killed the leader. One man ran away, promising a terrible vengeance… which he showed up to carry out about 30 seconds later. I killed him and somebody else ran off, promising a terrible vengeance, which they showed up to carry out - etcetera, etcetera. I realise vengeance doesn’t have a minimum cooking time but I do like a bit of suspense with my vendettas. This conga line of grudge matches ended when I ran into somebody robbing somebody else. I blind-sided the bandits, managing to murder the lot this time and stave off further reprisals. The victim engaged dialogue and thanked me profusely - all the while firing arrows into my head. Life is complicated on the frontier. The AI in general is that familiar balance of vigilant to the point of smelling you through ceilings, and charmingly unaware, reacting to things like knocked-over buckets as though the circus is in town, then forgetting all about it. Later on, I fled a basement after killing a whole brace of characters by essentially dumping my entire supply of dynamite on the floor. I crept back down later to collect the spoils, and found that the sole survivor had made herself at home in an adjoining bedroom, living out a blissful endstate punctured by moments of acute trauma whenever she sauntered through and re-discovered a heap of incinerated corpses. I didn’t have the heart to interfere. Weird West is a game of loose ends. As regards its unscripted narrative and world elements, that’s to its advantage. Take that woman in the basement - on sneaking closer I realised that she was, in fact, a named character with a backstory. A few hours before, I’d helped reunite her with a lost friend, after stumbling on the latter’s kidnapper in another town, way across the map. There’s something poignant and invigorating about how the pieces of this game come back to haunt you - given a decent interval, anyway. Other elements, however, feel like they’re still searching for their place in the puzzle, their potential fizzling out like dynamite in the rain. I suspect that, above all, what this eldritch vision of North America’s settlement could have done with is a bit more time.