In this edition, it’s time to get wild for peripherals that cross over the traditional boundaries. We go racing with the Wooting Two HE analogue keyboard, add RGB to our ears with the Razer Hammerhead True Wireless earbuds, and take a flight with two Lexip joystick-equipped mice. Here, nothing is as it seems…

Racing keyboards: Wooting Two HE review Mobile RGB in-ears: Razer Hammerhead True Wireless (2021) review Mice you can fly with: Lexip PU94 and NP93 Alpha review Next time on Will vs Weird Tech…

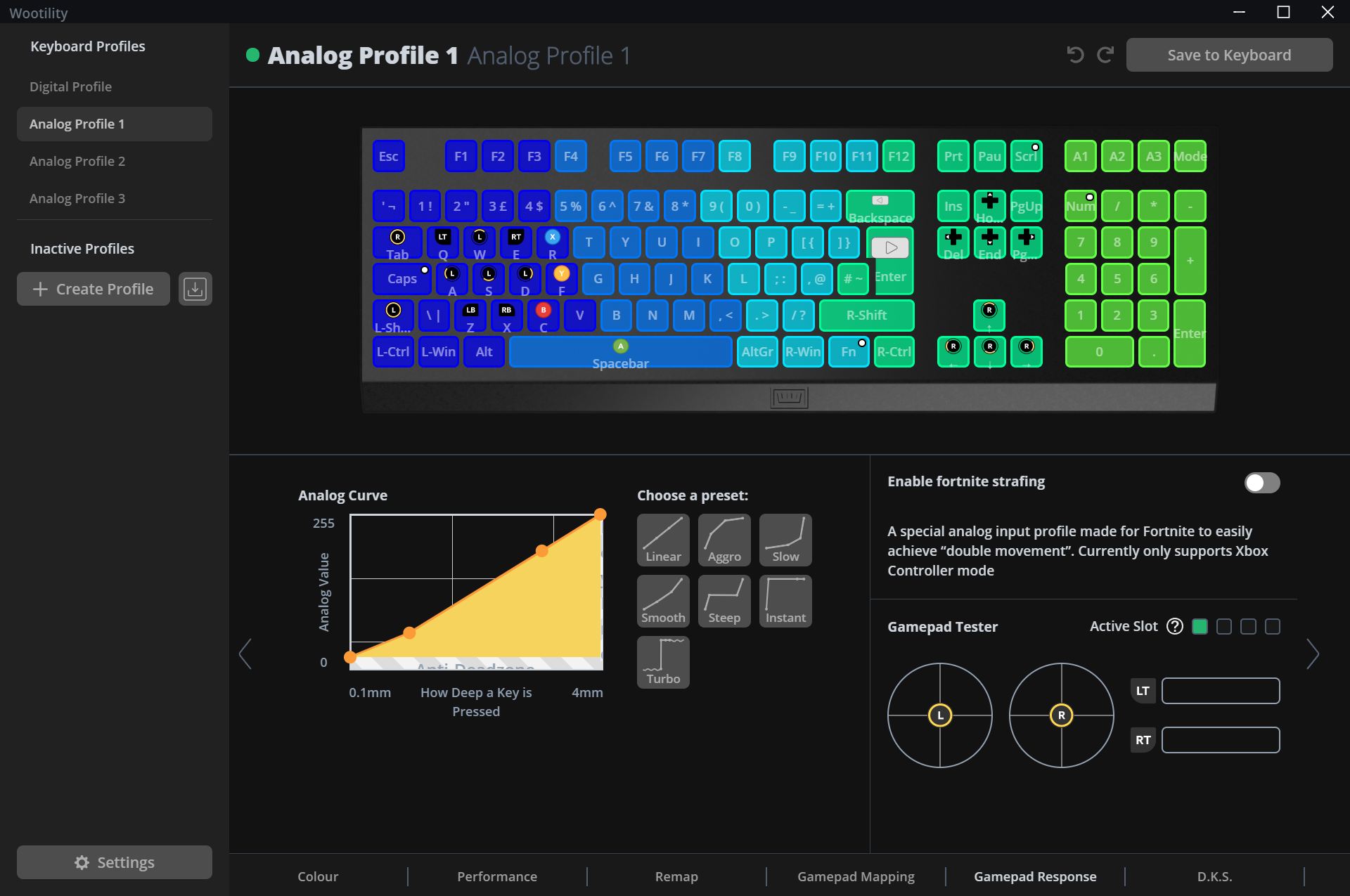

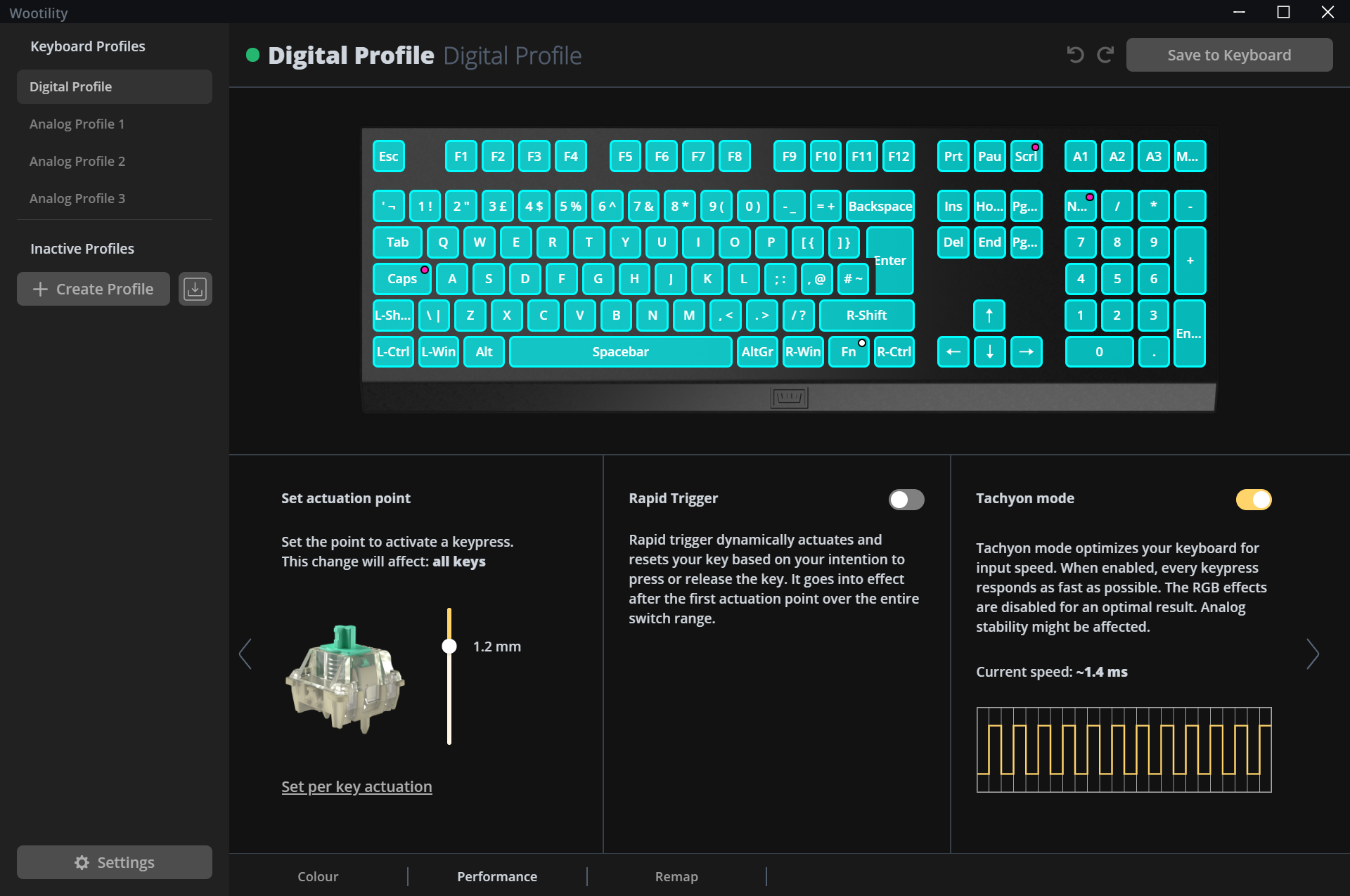

Instead of recognising a key press through a collapsing spring that causes two metal contacts to touch, these switches make use of a Hall effect sensor, which can detect the strength of a magnetic field. These sensors are placed on the keyboard’s circuit board, below each switch, and magnets are placed within the stem of each switch. As a key is pressed down, the Hall sensor gets a stronger reading, so you can detect with sub-millimetre precision just how far the key has travelled. This means you can detect a key press much earlier - after it’s travelled just 0.1mm, if you want - but it also unlocks totally new options that you simply won’t find on other keyboards. For example, each key could become an analogue input, like a trigger on a gamepad. Press it down a little, and your car in a racing game can accelerate slowly - but press it down further, and the acceleration will also be quicker. You could do the same with breaking and steering, giving you the fine-grained control of a joystick, wheel or trigger, while the other keys on the keyboard can remain as traditional digital inputs. You could also map multiple functions to a single key - you can activate one function at a certain depth, a different one further down, then two further different functions on the way up. For example, in Counter-Strike you might pull out a grenade (4) at the start of your key press, throw it once you press the key all the way down (left click), then switch to your pistol (2) and then your primary (3) as the key returns to its original position. Even if you’re using the Wooting Two HE as a traditional keyboard, you can change the point at which a key press is recognised - the actuation point. An early actuation point means your input is recognised faster, while a later actuation point makes it harder to lean on a key and make a typo. Normally, you can only change this by buying a keyboard with different switches, so to change it in software or by pressing a key is great. The software provided here is called Wootility, and contains all the standard keyboard settings - rebinding keys, changing lighting effects - as well as all the cool functions enabled by the analogue sensing. I tested the Two HE for around a month, trying to use its extra features as much as I could. The Ascent, a twin-stick shooter, was one early experiment - and here, the experience wasn’t great, as aiming accurately was simply easier with a mouse or gamepad - but if I didn’t have a gamepad and the game lacked mouse support, then the keyboard at least makes it comfortably playable. Need for Speed Heat, a racing game, worked far better - I set the usual WASD steering inputs as analogue inputs, while keeping the other keys for nitrous, hand brake and so on as digital inputs. This made it a lot easier to control the car through annoying drift challenges, keeping it from sliding when you’re trying to accelerate and from crashing into obstacles when you’re drifting. Counter-Strike was the final big challenge, and here the Two HE proved a surprising success. Normally, in the game, you have a choice of two movement speeds - silent walking (125 units per second) and faster but audible running (150-250 units/second, depending on weapon). With an analogue input, like the Two HE, you can actually set it up such that you walk faster than is normally allowed while still retaining your silence (134 units/second) - a genuine competitive advantage. Similarly, you can actually move at one third normal walking speed while retaining the same accuracy as if you were standing still - another genuine leg-up over the immobile competition! (Counter-Strike YouTuber 3kliksphilip demonstrates this adroitly here.) Of course, actually retraining your brain to half-press a key is a challenge, but after a few days it is something you can get used to. I wonder if we’ll eventually see Wooting sponsor a Counter-Strike team, train them in the ways of analogue input, and make the Two HE the must-have keyboard for eports pros… So is the Wooting Two HE worth buying? I think in general, the issue with an analogue keyboard is that you might not use its analogue functions in every game you play - unless you only play racing or gamepad-focused cross-platform titles. Thankfully, the Wooting Two HE gets around this by costing about the same as a high-end mechanical keyboard (£158), with a clean design, four extra keys, pretty RGB backlighting and high build quality throughout. (The only possible exception here are the default ABS keycaps, which I swapped for SteelSeries’ fancier-looking PBT PrismCaps, but most £100+ gaming keyboards use ABS keycaps as well so it’s hardly a drawback for the Two HE.) If you’d normally consider a £120 mechanical keyboard, then paying £40 extra for all this extra functionality - some of which provides a genuine competitive advantage - is a pretty good deal in my eyes. Compared to the earlier model, these in-ears have better battery life, but be aware that the RGB lighting and ANC do reduce their expected use time. Both features disabled gets you the maximum 32.5 hours (earbuds plus case recharges), RGB enabled and ANC off nets you 27.5 hours, RGB disabled and ANC enabled is 22.5 hours and both enabled is 20 hours. Even with both features turned on, I still went a week without recharges, with a few hours of use each day, which is more than sufficient for my needs, and the case recharges quickly using USB-C. The ANC function isn’t the strongest I’ve seen - something like the on-ear Sony 1000XM4s are significantly better at blocking out noise at different frequencies - but it’s still well worth using despite the battery life hit and pushes these beyond standard in-ears in my estimation. Whether they’re worth the £130 asking price is up to you, but I now rarely leave the house without these in my pocket, and my bus and train journeys have become much more blissful as a result. Well, the first of the two mice, the NP93 Alpha, is in other respects fairly ordinary, although it does have a surfeit of circular, extremely low friction feet to help offset its relatively high weight - it positively skims the surface of the mouse pad. The second mouse, the PU94, is more radical: it has a second joystick to complement the first. Basically, the shell of the mouse and the base can move independently, allowing you to tilt the mouse left, right, forwards or back without moving it on your desk. This gives you six axes of movement - both vertical and horizontal values from each of the optical sensor, joystick and tilting shell. Actually using the PU94 in games like Flight Simulator 2020 is interesting. It all works as described, but getting your head around what each axis does is not a simple process - and neither is binding each function in the game settings. The normal mouse and joystick are fairly natural, but it becomes a bit challenging tilting the mouse from side to side or back and forth without actually moving it on the desk. In flight sim, I had normal mouse movement controlling the camera, the joystick controlling pitch and roll and the shell tilt controlling the rudder. There were a few… unfortunate… accidents, but when I was focused enough to do everything properly, you could legitimately control the aircraft with one hand, which is pretty spectacular. Using the mice in faster-paced games was more challenging. The heavy weight of the mouse (141g) makes it a challenge to move quickly and accurately, despite the feet, and trying to combine tilting with mouse movement was liable to end in disaster. I think this unusual rodent is best suited for creative applications - say, controlling the viewport in a 3D modelling application - or flight simulators, rather than most other games. That’s not to say that Lexip’s marketing is without merit, but I think you would need to spend a lot of time practicing with the mouse in order to use it smoothly - and simply using a keyboard and mouse, or a regular gamepad with two joysticks, is likely to be a better and certainly more widely accepted use case. Still, if you have only one hand free, or you do use any kind of creative software that involves moving in 3D space, then I think the PU94 is well worth trying out at £69. The NP93 Alpha is an easier recommendation. Having a joystick under the thumb makes a lot of sense, and there’s a less heavy cognitive demand on integrating this into your play. Likewise, the joystick may be useful as an extra axis in 3D applications, while the lighter and more traditional body is easier to use for regular office and gaming tasks. It’s also a lot cheaper, at £43, and serves as a great value alternative to the £115 Asus ROG Chakram - which admittedly does have superior gaming credentials, wired and wireless connectivity, swappable switches and so on. Ultimately, the basic idea of a gaming mouse with a joystick is a sensible one, and one that deserves further exploration by users and mice makers alike.