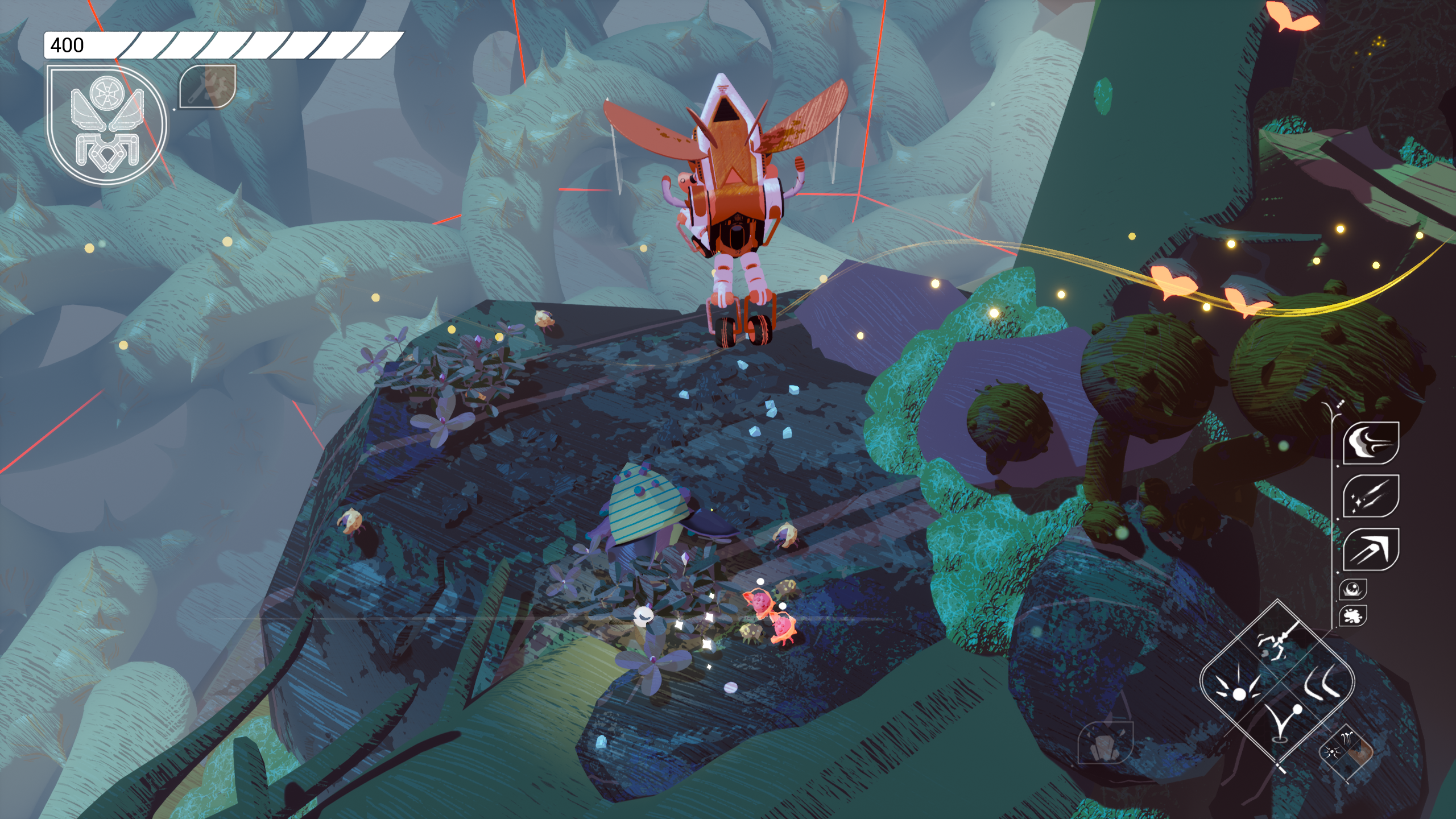

Like Robert Hooke’s flea! There it is in Micrographia, 1665 or whatever. Fleas are so small, aren’t they, but this one is a giant. It seems to hover on the page. And the body! Armour plating, those dangling legs, concertinaed for action. Those tiny eyes, and is that a moustache? No, not a moustache - this flea looks more like a machine than a living thing. Something a tiny operator might climb aboard before setting off to scorch the earth somewhere. Horrors. It’s not just the flea. A few years back, an insect with leg gears was discovered! Gears, naturally occurring in nature, the first proof of its kind. Again, this hopping charmer is both animal and machine, toothed sections meshing, controlling the hopping action. Insects, nature, pinecones: these things are astonishing up close. And here we are with Stonefly, then, an action-adventure game that plays out high up in the trees, and simultaneously right down there on the Micrographia scale, the Robert Hooke scale. Branches are highways here, hollow trunks look like canyons and river beds. Scattered leaves are little arenas. And you control a tiny inventor named Annika who pilots a little insectoid mech. You know, armour plating, dangling legs, concertinaed for action. Gears meshing. Stonefly is the new game from Flight School Studio, whose previous work includes Creature in the Well, which played out as a post-apocalyptic hack-and-slash powered by pinball and alive to the horrors of sudden shifts in scale. A huge arm descending from below, the sudden realisation that there are worlds stacked beyond this one, inhabitants with their own agendas. Stonefly is very different. It’s inspired by the natural world rather than the penny victories of mechanical arcades, and it’s inspired by those who have in turn taken inspiration from the natural world. Artists like Charley Harper, the mid-century wonder, who can conjure Northern Cardinals from a teardrop of red paint and a few dots and lines, whose minimalist birds and bugs seem not so much still on the page but frozen briefly between one swift movement and the next. The challenge here, before you get to a game, is to take the brilliant flatness of an artist like Harper and turn it into 3D. Stonefly is 3D, but it uses a lot of illustrated textures on the grass, the branches, the shells of its bugs, to make the world feel hand drawn. It’s a beautiful game in screenshots and in movement it’s even better - endearing and alarming by turn. Leaves! Bugs! Annika has taken her father’s mech out for a drive and it’s gone missing. Now she has to get it back. That’s the plot. The game itself is a fascinating blend of ideas, criss-crossing genres as if the boundaries simply aren’t there, which they shouldn’t be really. How nice. This is an exploration game as Annika searched the branches and tangles of her arboreal world on the trail of that cherished mech. Knocked back to a bit of a junker, though, Annika must also be on the lookout for the material she’ll need to harvest for upgrades. Upgrades mean better parts for the mech, and customisation options for how it looks. And then there’s the fact that Annika’s an inventor, a lovely shortcut that means that at certain moments ideas for parts just come to her. This system already appears to be gloriously deep. In a demo I watched over Discord earlier this week, Annika started by fixing the legs on her junker, a kind of metal hermit crab with a bleached post box instead of a shell. To fix the legs she needed to create a tool. Resources and trade-offs. And then onto the choices of what do next: do you want to jump higher and move faster? Do you want new abilities, like decoys or a more powerful push attack? This ties into the other part of the game. Stonefly is a combat game, but with a non-fatal twist. You fight bugs, but you’re really only trying to stun them and push them off branches. The developers say it’s a bit like King of the Hill. Here’s how it works. You’re after resources, which grow in the world in little nodes. But the resources attract other bugs, so you have to fend them off and steer them out of the way while you take the resources for yourself. Some bugs are pretty harmless. Others are big and mean - pretty much bosses, with beetle antlers and special moves. Some have a trick to them - maybe they can only be stunned and pushed once you’ve flipped them onto their backs. Got all that? Then picture a lot of bugs, scattered about this spindly, leafy world. Do you want combat or stealth? How do you want to approach each encounter? What is your mech currently rigged up for? This is Stonefly. The key to combat from what I’ve seen is mastering your mech’s ability to take to the air. It’s a limited thing, but a mech is far more maneuverable in the air than on the ground. Which means, in turn, that some of the enemies will exploit that by bringing you down to their level. Played by a developer who knows what he’s doing, the whole thing is a dance of action - a Flamenco, with lots of dodging and stomping. But it’s hard to get that fluent. Fluency, I gather, is a sign of experience here. Make the bug Flamenco look effortless. Stonefly is a lovely game to watch. Dialogue scenes play out with lovely pictures of the main characters next to their text, while the trees are alive with gusts of wind and updrafts that can be used as fresh routes. Every few minutes a new bug machine toddles out of the darkness, horrifying and fascinating, a challenge but also a gift. The world is violent and has a touch of destructibility, but I believe the developers when they say the tone is also one of contemplation - long stretches out in the branches searching for the next step in the trail to getting that mech back. In between exploring you return to base and upgrade your mech, or you track down special high risk levels where the mineral reward is great but the bugs you’re up against are more fearsome and numerous, the whole thing playing out on the surface of a truly monstrous insect, a moveable feast. And why do all this? Because of Dad’s mech. I get a glimpse of it in the presentation, and guess what? It looks like a pinecone, a tight, waddled knot of silver-grey primes, wobbling around on the ground and then opening out, catching the breeze and taking to the skies.