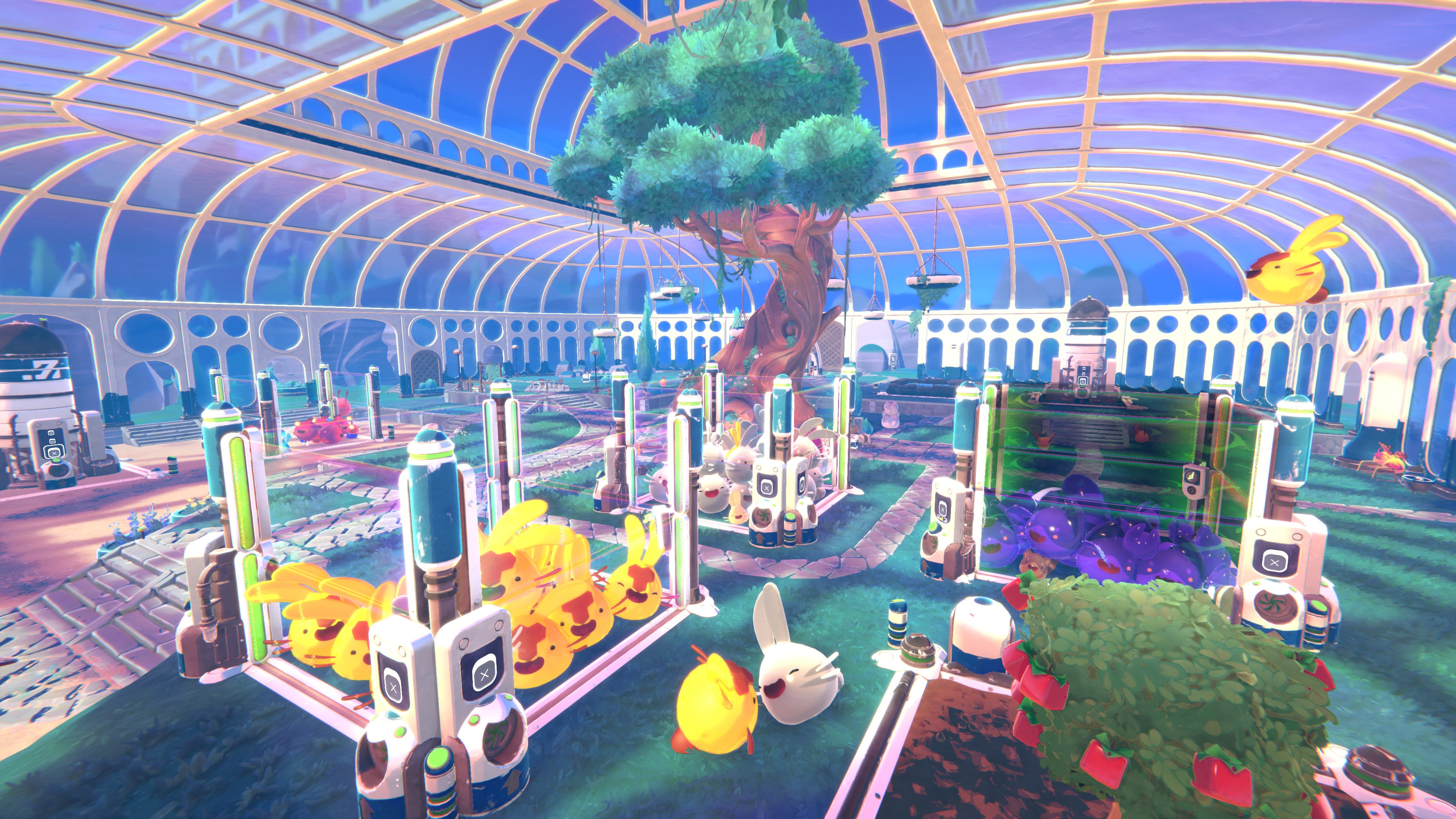

Crary takes this argument in a number of fascinating, alarming ways. What he doesn’t mention - and I understand this, I guess - is a great-uncle of mine who used to own a turkey farm, and had heard that turkeys were so stupid that when the lights went off they thought the day was over. He rigged up a system in his turkey farm, a farm which clearly should have been shut down by the authorities, in which the lights continually went on and off, the theory being that the turkeys would age by a day each time this happened, and would be ready for market sooner. I don’t need to add anything at this point, but I will: my great uncle was not a very nice man and should not be interpreted as the hero of this story. Both of these things - Crary’s illuminating book and the involuntary memory about a family member that it prompted - created what is basically the single least ideal mindset in which to experience Slime Rancher 2, which is out in early access at the moment and is taking over the world. Slime Rancher 2 is a thing of joy: exploration and curiosity delivered in thick, buttery pastels. But it is also the kind of horror that Crary would potentially identify as pure capitalist indoctrination - a game that people are exposed to rather than asked to play. I don’t think that would be entirely fair, but everything about this game is contradictory and challenging. Here’s the basis of Slime Rancher 2. Like the first game you are dropped into a colourful world with a gadget that allows you to vacuum up colourful slime creatures and deposit them elsewhere. Quickly you start putting them in pens, and feeding them, and harvesting their waste to spend elsewhere and create various game loops that are undeniably pretty compelling. This is not the subtext, incidentally: this is the text of the game, as it were. Slime Rancher 2 is not trying to hide you from the fact that you’re basically a cheery battery farmer - at least at the start. The difference between the first game, which I have not played very much of, and the second game, which at the time of writing I have only played for a lazy morning, is that the world has changed so much. Slime Rancher 2 is absolutely gorgeous, a kind of duvet-soft archipelago filled with thick waving grass, sun-warmed rocks, and dreamy coastal vistas. It is such a pleasure to explore, I would be out there wandering even if I wasn’t lured through it with the promise of slimes to capture. And maybe this is the point. The danger, I think, of seeing capitalism everywhere, as I am in the weeks after reading that Crary book, is that I also lack the insight to see what is being said about capitalism - or what might be being said about capitalism. To put it another way, perhaps what’s interesting about Slime Rancher 2 is not what it makes you do, but what it allows you to make yourself do. As a good example of this, there’s the process of harvesting waste. Once fed, slimes will produce little jewels of waste which you want to collect because they power the economy. But the pens I put everyone in at first are small and busy with slimes, and the waste is scattered in amongst the moving bodies. What I instinctively do in this situation is just vacuum everything up and let the vacuum sort it - into waste and into slimes - and I then reinject the slimes alone into the pen. Neat. And efficient! But think about this: the vacuum you’re given in Slime Rancher 2 is cute, but it’s also absolutely gun-like, which makes me think that the experience of being vacuumed up in the first place might not be completely delightful. So to be vacuumed, expelled, and then re-vacuumed and re-expelled just because I am too lazy to sort creature from waste in the real world - might it be that the game is encouraging me to interrogate my own behaviour? I was thoroughly confused by all of this for a long while. I have continued to play, and watched the game open up in the familiar ways that games open up. I can buy new gadgets and work towards opening up new areas. The slimes have natural enemies that I can learn to defeat - so maybe, really, I’m protecting slimes rather than purely exploiting them? Maybe? On top of that, when I return home after resource gathering, my battery farm increasingly looks like a chaotic frat-house. The slimes have bounded from their pens to the extent that I won’t bother building many more of them. They’re breeding and creating new variants. They’re knocking about and escaping and finding food and all that jazz that makes me feel just a little less terrible about my role in their lives. So what is it? Is Slime Rancher a cute series that happens to accidentally be about doing something awful? Or is it an ingenious series that often uses its cuteness to explain the potential for awfulness already present in the player and their world? Luckily, to the rescue - as is often the case - came Kirk McKeand, with this fascinating interview with Slime Rancher 2’s game director, Nick Popovich. And the answer - as I read it, and this might be just me - is that it’s a muddle. The whole series started as a much more open satire of capitalism, but then it softened. It softened because plan met implementation and it all got a lot more complicated. It’s worth quoting this bit in full: “There were a lot more dark things in the original design,” Popovich says [talking about the first Slime Rancher]. “If you remember the movie Moon – where that person’s out there and it’s actually a horrible cloning replacement program – it had a little more like that in it, but not for very long. There was a whole bunch of stuff I wanted to say, and I think part of that was like, ‘Oh, you’re in indie games now, you get to do these things and no one’s gonna tell you not to.’ Then as soon as we had slimes smiling back at us, I realized I could say some of these things, and I can have a personal love story in this game and everything, and some people won’t even notice, or they’ll realize it later. “I still think one of the greatest magic tricks you can do in entertainment is have something that kids watch and love, and then they either grow up, or they’re watching with their parents who get something different out of it. I think that’s the masterstroke. I know there’s a bunch of kids out there who play through Slime Rancher and they never read the Slimepedia, they never read the love story that’s in there, or little bits of philosophy or see what the game is even about – you need to take care of these creatures, there’s a relationship you have with them. They’re not just cattle.” My take is that when you bring a bit of life into a game, things start to slip from your control. If you make games the right way, they get a bit of wildness to them: the neat satires you plan don’t fit, but the mocking ghosts of those satires make cheerier interpretations quietly fraught too. So Slime Rancher’s cute, and it’s horrible, and it’s both of these things even when they contradict one another. And why should it make sense in any easier kind of way? So where do I end up on this? If I had to sum up what I suspect at the moment, then, it’s that Slime Ranger 2, with its grinny, pooping slimes and unicorn ice cream vibes, both exploits and explores our dangerous ability to live with serious contradictions. And maybe it’s a bit about the way that the warm familiarity of good game systems and loops encourages you to justify what you’re doing when everything just feels so nice. But it’s the idea of ending up on a single interpretation which is probably the problem here. What I love about this game is that it’s clearly born of ambivalence, of ideas that could only ever get slightly away from everyone and refuse to settle down. This game isn’t solvable, I reckon, and in 2022 that’s about the highest compliment I can offer.