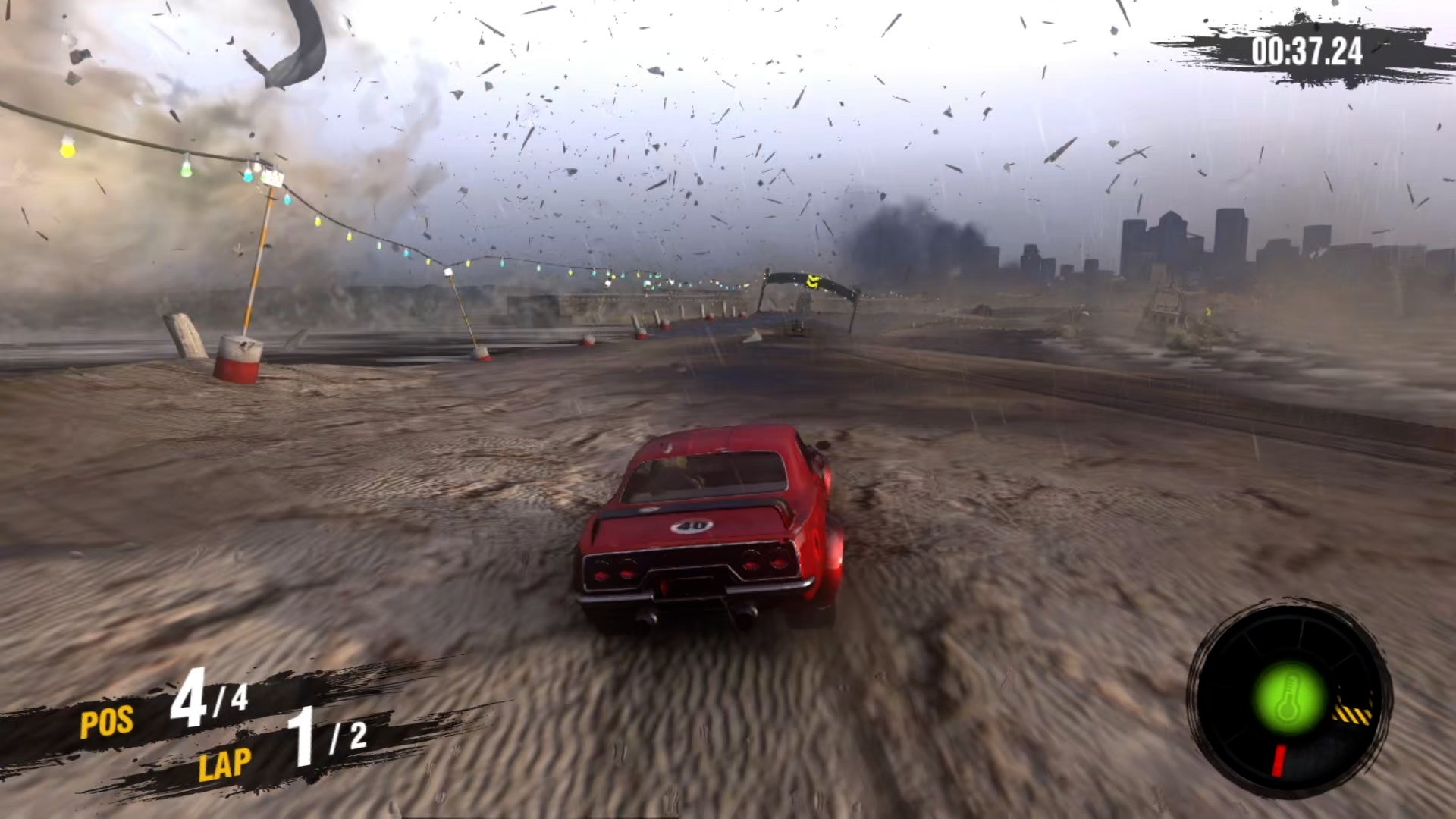

Originally known as ‘Stampede’, Motorstorm was originally envisioned as a celebration of dirt racing featuring asymmetric vehicle battles, massive tracks and complex physics simulation with up to 48 vehicles in a single race. The goal was to create something worthy of the ’next-generation’ label but there was just one problem - the next-generation platform it was being designed for was nowhere near ready and things would get a whole lot worse before they got better, and that’s where the infamous ’target render’ from Sony’s E3 2005 press conference comes into view. This now infamous showing blew people away at the time, promising a level of fidelity that seemed impossible - and that’s because it was. Phil Harrison famously took the stage during the show presenting games that were in-development via the use of bombastic trailers. Motostorm’s short trailer featured unbelievable chaos, physics and destruction as a herd of vehicles storm their way across the landscape. For the Evolution Studios crew back in Runcorn, England, however, what should have been an exciting moment for the team with the announcement of their next game, turned into a moment of panic when Phil Harrison himself suggested to the press that this Motorstorm trailer represented actual gameplay. It didn’t. The trailer had been created by VFX and CGI specialists known as Realtime UK - it was just a rendered flavour piece never intended to publicly showcase the game, but its misrepresentation at E3 put a lot of extra pressure on Evolution - a team that didn’t even have access to PlayStation 3 hardware yet; it was still being prototyped on PCs that supposedly matched the specs of the real deal. The studio wouldn’t receive actual PlayStation 3 development hardware until months later - leaving them with just one year to build the game. I’m told it was a difficult time - the hardware did not meet expectations and the super-tight deadline was always looming. Plus, even adjusting things such as the handling characteristics of each vehicle required tweaking values in a text file then recompiling the game resulting in lots of waiting. Beyond this, the programming team found themselves implementing all sorts of new techniques that none of them had used before all while dealing with early, unfinished SDKs. The game’s creative director later revealed that, after seeing an early demo of Motorstorm, Phil Harrison took them aside to berate them calling the team at Evolution the ‘worst in the world’ in the context of Sony’s range of internal development teams. However, it’s clear in hindsight that, even in the face of adversity and technical challenges, the crew at Evolution Studios were driven to deliver something as close to its original vision as possible and as its 2006 demo confirmed - this was the real deal. The final game was first released later that year in Japan, before arriving in a more complete form a few months later in the US and Europe. It also received a later re-issue known as Motorstorm Complete featuring all of the DLC tracks and updates on disc. As the initial concepts suggested, Motorstorm is all about asymmetric racing - that is, races take place with a variety of completely different vehicles with unique handling characteristics ranging from dirt bikes, buggies and even semi-trucks. This concept is unique even today but it’s the marriage of this idea with several key design elements that allows it to work. So, firstly, there’s the track make-up itself - Motorstorm features wide tracks with each track offering drivers multiple routes that often criss-cross one another. The tracks themselves aren’t simply tubes like many racing games before - they’re proper open spaces with carefully crafted routes running throughout. You always have your central route, filled with mud and debris, but there’s also higher routes or two running along the edges of the track as well as a wildcard route that can send you off in all sorts of directions. All these routes intersect regularly or simply pass above or below one another leading to a real sense of chaos. As you drive through a valley, for instance, you’ll see other racers launching just above your head, crashing down on the ridge on your upper right. This sense of busyness specifically lends the game an energy quite unlike other racing games of that era. It’s immersive and impressive - you get the benefits of a track-based design with some of the freedom people love about modern open world racing games. It perfectly straddles that line. Then there’s the driving model and simulation itself - Motorstorm comes from that beautiful era between 2005 and 2007 when developers seemed as interested in pushing complex simulations as they were high-end visuals. To that end, Motorstorm is one of the first games on PlayStation 3 to utilise Havoc physics. In fact, the development team worked closely with Havoc specifically to get this middleware up and running well on the hardware. Motorstorm takes advantage of this is three key areas - firstly, with rigid body physics. This is applied to vehicles and trackside objects alike, reacting realistically to forces exerted upon them, in addition to larger structures built from a collection of objects that disintegrated when colliding with them - the closest we got to the mayhem in the target render. The third major area where physics comes into play involves the vehicles themselves - specifically the progressive damage system. As you race and slam your car into other vehicles or objects, you’ll see that metal bends, body panels are lost and your car is eventually reduced to little more than a driver, frame and engine. It’s fully locational - so you can lose a door or a bonnet or any other piece independently of the rest of the vehicle. The combination of physics simulation along with very carefully tuned vehicle handling results in something that feels remarkably visceral and substantial to play. There’s this physicality to it that, honestly, I’m not sure any game before or since has quite matched. The way the tyres, suspension and frames bounce around and react to the terrain is so satisfying. The simple act of driving feels good in Motorstorm. That ties into the intersection between driving and track design. Asymmetric racing is a nuanced topic as such a variety in vehicle classes necessitates careful balance and design. Basically, if you’re driving a dirt bike and your opponent is driving a giant semi-truck, the relationship between the two needs to be simulated, right? And that’s what makes it so exciting. Lighter vehicles can often move faster but they’re basically moving targets for larger trucks and buggies. Handling is also influenced by the terrain itself - dry rock behaves differently from thick mud. The higher routes favour faster, lighter vehicles like bikes while larger trucks are better suited to racing right down the middle. Events are designed to take this into account as well - you’ll have races with mixed vehicles but also events like this where you have a pack full of bikes with one semi-truck terrorising the middle. It’s a blast. This is enhanced by pseudo-track deformation as well. Motorstorm uses normal maps to generate tire tracks in mud and dirt - these are persistent and have an impact on the actual handling. This means, on laps 2 or 3, that centre route will have become muddier and more difficult to drive through especially in smaller vehicles. The original Motorstorm, as with the games that follow, remains an exclusive to PlayStation 3, with no ports or remasters for more modern platforms, meaning emulation via RPCS3 is the only way forward. This emulator is genuinely amazing at this point (assuming you have a top-tier CPU!) and I’m happy to report that the two sequels to Motorstorm run very well in RPCS3 but the original Motorstorm is, unfortunately, not quite there, with vehicles lurching back and forth while driving. However, it does give us a taste of what’s possible - you can massively boost the resolution to 4K or even higher, while the game’s overlong load times are nearly eliminated. And when it works, wow, seeing this game in 4K at 60 fps really demonstrates just how beautifully designed the presentation in Motorstorm really is. So, yes, Motorstorm still holds up today, but Evolution one-upped themselves with Motorstorm: Pacific Rift - the idea being to move the racing festival concept to a deserted island full of ruins, tropical rain forests and volcanos. In many ways, it’s what one might describe as the perfect sequel - a game that builds upon the strengths of the original concept while pushing new ideas in all directions. It’s more refined, features more content and is beautifully paced - a brilliant game that led to Evolution Studios and its smaller satellite studio Big Big being acquired by Sony. In Pacific Rift, the main events are divided up into four elements: Earth, Air, Fire and Water. Each category represents a unique style of environment to race in. It’s not just racing, however - new event types are introduced, such as elimination or checkpoint events, to add some variety to the mix. Evolution also added a new vehicle class, the Monster Truck, as well as more flexible single-player options, online play and even split-screen. There’s just so much more content and variety here compared to the original. Once you start playing, however, it’s clear that the game is a different beast - the vehicle handling feels completely different compared to the first game. Handling is faster and less floaty than the original, but it manages to strike a nice balance between responsiveness and bombast. It works well. One of the key new features here involves the boost system - in the original, you would hold boost to gain speed and a meter would fill - when it reaches the top, you explode due to overheated. With the sequel, however, it uses water and fire to influence your temperature. Basically, if you drive through water, your accumulated heat is reduced immediately allowing for more strategic boosting opportunities. Conversely, if you drive through fire or near the edge of a volcano opening, your engine overheats more quickly making it difficult to boost. The tracks feature significantly more variety this time around too. While I love Monument Valley’s aesthetic, Pacific Rift takes the players to so many different locales and those new environments have an impact on your driving. Wide-open mountains and volcanos allow you to run wild but there’s also sections with tight, man-made structures as well as thick jungles which demand more precision in your driving. The criss-crossing nature of the tracks remains intact as well, which is always good fun. In building Pacific Rift, the team went back to the drawing board, completely re-engineering the entire engine rather than simply building upon work from the original game - no doubt the result of technical debt incurred by shipping a game so close to the launch of PS3. The new iteration of the Evolution engine brings some nice improvements to the table allowing for even larger, more varied tracks. One of the key new features is a robust vegetation system - a requirement for the thick, jungle environments present in many of its tracks. Trees, bushes, grass and more are all rendered beautifully but what really sells the effect is full touch bending. That’s right - when you drive your vehicle into the vegetation, it snaps and bends realistically. It’s similar to what we saw in something like Crysis, though at a smaller scale of course, and it stands out as a feature that we really don’t see that often even today. Pacific Rift also introduces screen space crepuscular rays for the sun allowing streams of light to pierce darkened areas provided the source of the light is on-screen. Another forward-looking feature for the era. For water, the developers primarily use a form of planar reflections while indirect lighting is handled using global ambient cube maps. Keep in mind, however, that this was still very much a game of its generation - it uses forward rendering and lacks many of the more advanced features that would begin to arrive in the next few years. However, this approach has benefits allowing things like particle shadows with ease not to mention performance efficiency and relatively low input latency. Like the rest of the series, of course, Pacific Rift is designed to run at 30 frames per second. Evolution had originally wanted to target 60 for the first game but it’s clear in retrospect that it wouldn’t have been possible and it’s not possible here either - at least on a real PS3. Between its features, visual fidelity and the thrilling gameplay then, Pacific Rift is a must play for arcade racing fans but, of course, it remains constrained to a single console - the PlayStation 3. However, unlike the first Motostorm, Pacific Rift runs beautifully at 4K60 via RPCS3 - again, assuming you have a top-end CPU to hand. With Evolution at the top of its game, spin-offs followed, spearheaded by Big Big’s Motorstorm: Arctic Edge for PSP, a carefully pared back rendition of the game, which eventually ended up on PlayStation 2, produced by Virtuos, no less - a studio still around today and known for its porting prowess. Remarkably, nine years after the system’s Japanese debut, PlayStation 2 enjoyed its own take on Motorstorm. However, only one further series entry would arrive - Motorstorm Apocalypse, the final mainline entry in the series, and a game beset by calamity and literal disaster. In the last game, players are dropped into a city under siege from a range of natural disasters - storms, earthquakes and other natural events rip apart the tracks as you race. It’s a game that has big ideas that fall short in key areas but also, it was victim to unforeseen circumstances that had a real human cost outside the world of video games. On March 11, 2011, a magnitude 9.1 earthquake occurred just off the coast of Japan. This powerful quake resulted in a devastating tsunami which slammed the island nation, leaving destruction in its wake. It also resulted in disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. It was a terrible tragedy that impacted so many people. Some of the content may have hit too close to home, but the timing didn’t help either. The original release date for Motorstorm Apocalypse was March 16 - just five days after this disaster hit - and so, the decision was made to delay the game and cancel all marketing. It did still arrive in Australia as planned and its European date was only pushed back a couple weeks, but it was completely cancelled in Japan, while the US release date was moved to early May. And then, further misfortune befell Sony. In mid-April, less than a month before the release of Motorstorm Apocalypse in the US, the PlayStation Network was hacked and personal information compromised. This attack resulted in a service outage that would last nearly one month. Motorstorm Apocalypse launched during this period with no marketing and no online multiplayer. The circumstances around its release could not have been worse - but the game itself is absolutely fascinating. Motorstorm Apocalypse represents a dramatic shift in the tone and design of the series. At its core it’s still about driving one of many vehicle types around large tracks but the themes are completely different. The main single-player portion is now driven by a story told using video sequences. The writing and animation work was all outsourced to another company and, while I like the concept in theory, it never manages to gel with the action itself. The game itself features the kind of shift in design we don’t see too often these days - it feels like Evolution really wanted to try building something fresh and new while still delivering the classic Motorstorm DNA. In the first two games, it was the battle between you and your opponents that served as the primary focus - this is what led to so many interesting, dynamic moments. For Motorstorm Apocalypse, however, it’s less about racing and more about surviving as the tracks themselves constantly change. Delivering this required some major changes to the underlying technology - for the vision to work, Evolution would need to be able to drastically alter the track itself including the ability for players and AI to drive on top of collapsing structures. It needed to support more dynamic lights, advanced weather effects, a wealth of particles and more. So, firstly, the decision was made to evolve from a forward renderer, as seen in the first two games, to a semi-deferred light pre-pass renderer. This allows increased flexibility in terms of dynamic lights and other features which were necessary to deliver on the concept. Furthermore, the team implemented a wide range of new features on the back-end to enable faster iteration. The shader pipeline was now far more agile enabling artists to produce their best work without leaning on the programming team. Evolution also tapped further into the SPUs of the Cell processor - Pacific Rift already made this jump but it’s pushed even further this time even going so far as to implementing MLAA - an SPU-based post-processing anti-aliasing solution. Perhaps more impressively, the game’s rendering resolution was increased from 1280x720 of the first two games to 1280x1080 using the PS3’s 1080p mode for output. The initial goal here was to support a resolution more conducive to stereoscopic 3D but it had the side-effect of also improving the experience on a normal TV. The biggest challenge Evolution faced, however, was making the events work - at any point during a race, it’s possible to trigger massive, track-changing sequences that not only kick up expensive special effects and particles but actually alter where the player and AI can drive. Driving feels tighter and less floaty than the first two games, a change I don’t love necessarily, but this was the result of these dynamic tracks - Evolution had to massively increase downforce so that when a building starts to tumble, your car doesn’t go flying off into oblivion. Evolution also spent a lot of time working on the AI - the studio needed it to react to events, such as track destruction, but if it were keyed in too early, the player might see the AI dodge an obstacle that isn’t there yet, alerting them to the upcoming sequence. To that end, the team managed to craft a system that allows the AI to react at the same time as the player enhancing the realism. So there’s a lot going on under the hood but the point is that Apocalypse stands as one of the more impressive games released for the PS3. That said, there’s something about the camera FOV and the vehicle handling that doesn’t quite match the prior two games. It’s veering a little too close to a different style of racing game and loses something in the process. The nature of these environments also means there’s more debris to get stuck on - you’ll find yourself slamming into structures more often than the original games which can be frustrating initially. As far as performance then, the PS3 does a good job here and most races deliver a stable 30 frames per second - it can dip and dynamic resolution scaling is used, but it’s generally solid. Ultimately, Motorstorm Apocalypse is a good game but I feel it strayed a little too far from the festival vibe of the original and lacks the chaotic fun the series was known for. At the same time, once you accept that it’s a different style of Motorstorm, it’s easy to love. The tracks are extremely impressive to behold - going beyond similar games of this era such as Split-Second. It’s pretty clear that the release situation had a negative impact on overall sales and support for this game leaving it to fall short of expectations, most likely. The series did persist, however, thanks to a PS3/Vita top-down racer: Motorstorm RC - a radio-controlled vehicle take on the main games. Basically, this little racing game takes the themes from all prior Motorstorm games and shoves them into a slick little package. While you have multiple camera angles the game is viewed from above and the cars handle much like you’d expect from actual RC cars but it’s so much fun to play. All of this was made in just 10 months to boot making this a perfect side project for the team. It’s just a shame we never received a proper physical version - the retail Vita copy sold in Europe is just a code in a box. Technically, it appears to have been built on the engine powering Motorstorm Apocalypse as it shares many of the same rendering characteristics. The one downside to this, however, is the frame-rate - RC is capped at 30fps on both platforms which feels sluggish for a game with this much lateral motion. With the release of Motorstorm RC, however, the series ended and Evolution shifted its efforts entirely over to DriveClub - and this is where things basically went off the rails. DriveClub is an amazing game - one of the best racers of that generation - but it had a difficult time making it to market. It was delayed a full year, for starters, and then its servers were down for weeks when it finally did launch. Despite that, DriveClub is brilliant. In fact, the whole online aspect on which it was sold, while neat, is honestly not needed to enjoy this one - it has a robust single-player mode packed with content. And even today, it looks simply stunning: DriveClub makes the leap to physically based rendering in style with some of the finest vehicle rendering of its day. What really impresses is how dynamic every element is - every track has fully dynamic time of day alongside a volumetric cloud simulation and dynamic weather. The weather was added in a later patch, of course, and for my money, it’s still one of the best implementations in the business. Honestly, when I look at where we are today in terms of driving games, I feel DriveClub demonstrates just how ahead of the curve Evolution truly was. Release it today at 4K60 and it would stand toe to toe with the best. It’s that good. If you play DriveClub these days, the servers are long gone, but at least when enjoyed on a PlayStation 5, the load times are reduced to nearly nothing. It’s basically instant. Evolution also released a VR version of DriveClub, a Bikes focused add-on and more - the game was well supported and beloved but, alas, the release situation and the changing market ultimately resulted in the closure of Evolution Studios. Sony could have had its very own Forza Horizon competitor or a chance to return to Motorstorm but they tossed it aside in favour of zombies and Hollywood. It’s difficult not to feel a sense of loss. But rather than lamenting the untimely, unfair demise of a genuinely brilliant studio, let’s instead look back fondly on the good times. Motorstorm had a strong run: each of its three main entries offered something unique in the arcade racing space and love for the series remains strong to this day. It is, I believe, one of the high points of the PS3’s legacy - a brilliant series created by a legendary studio. In fact, I believe the legacy of Motorstorm is strong enough to warrant a proper return. Forza Horizon has shown the way, but the RPCS3 emulation demonstrates that even a remaster would do the trick. For now, though, the legacy of Motorstorm will never be forgotten. Long live the festival!