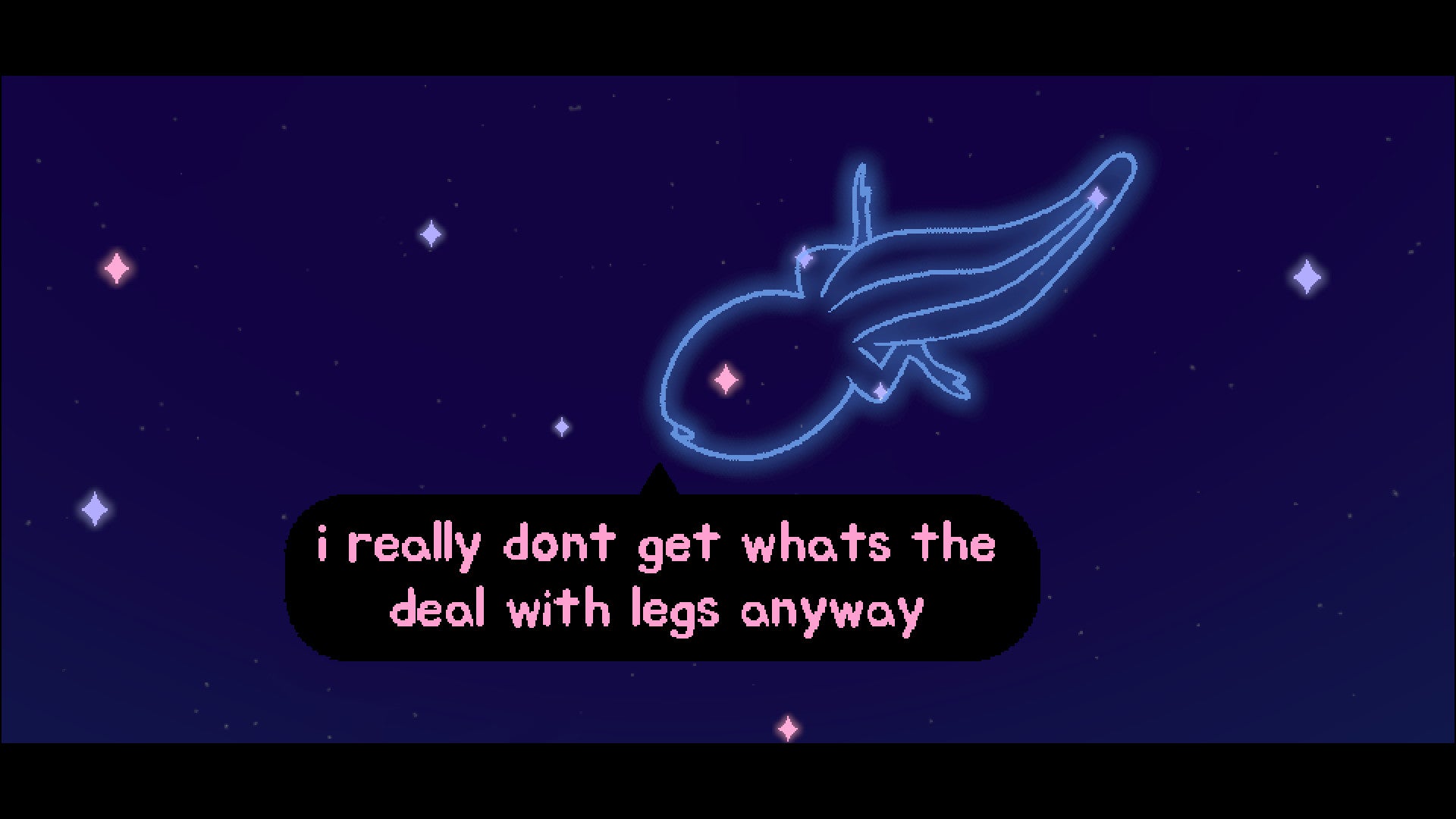

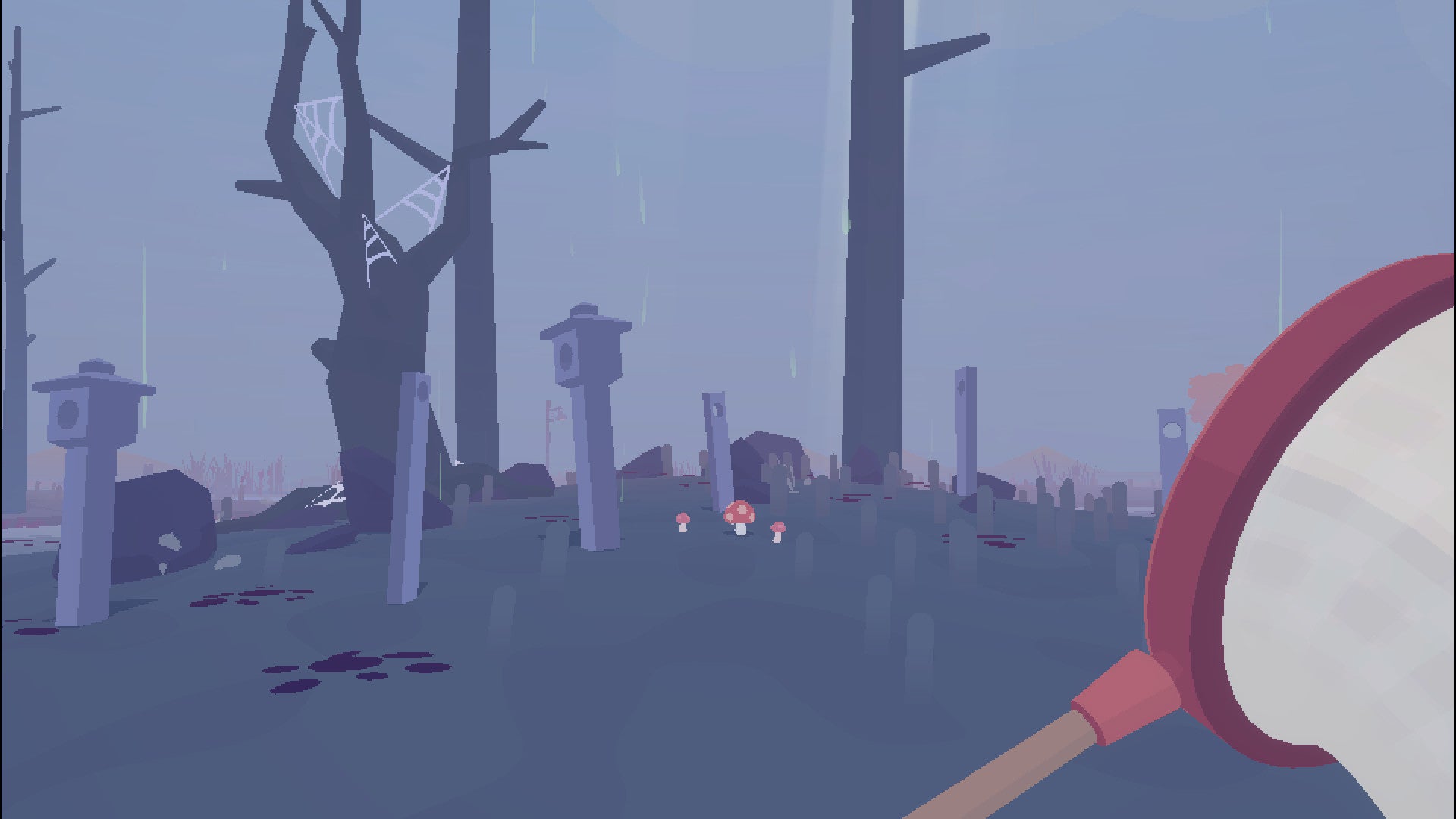

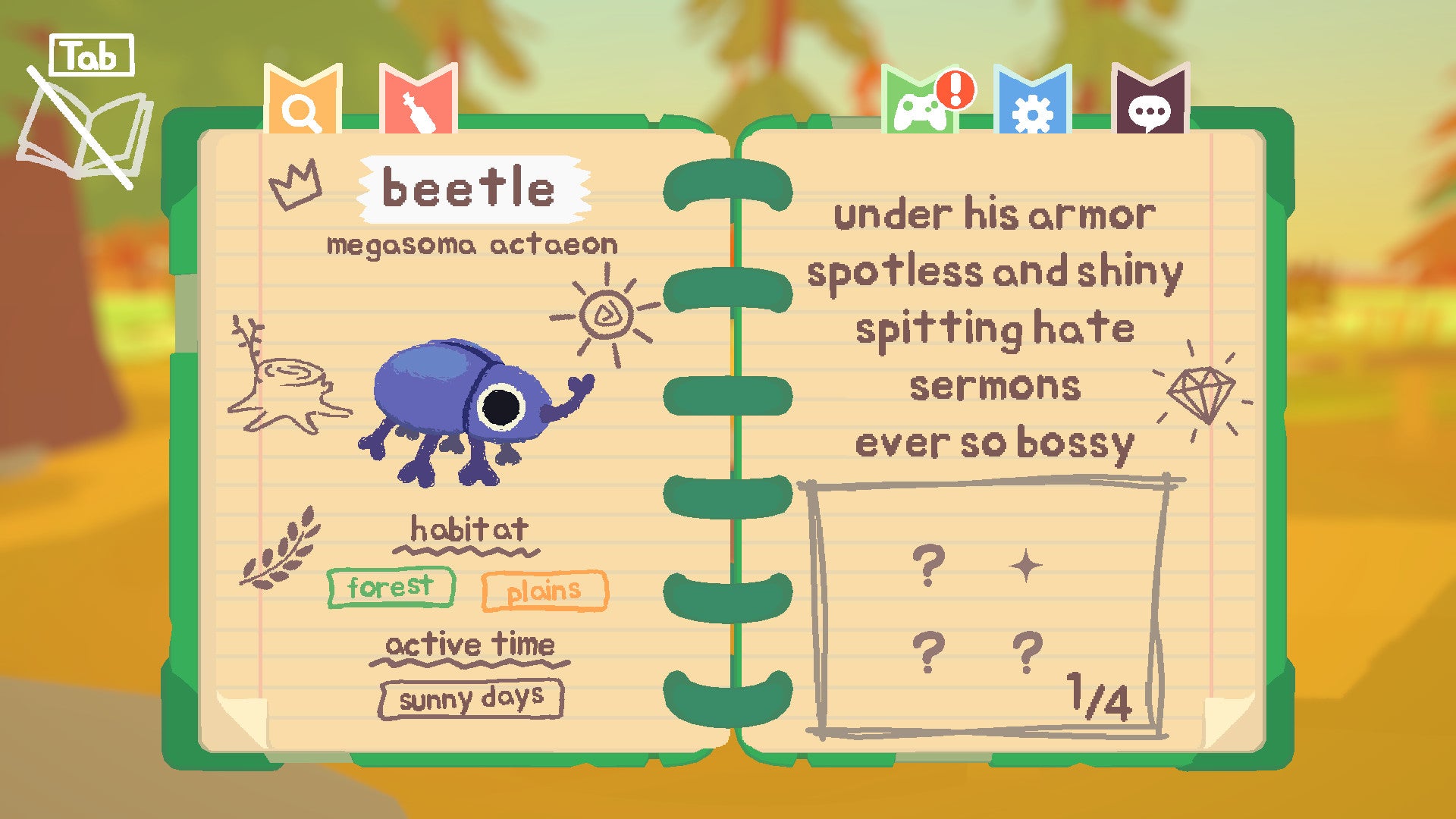

Star Maker is all about a journey through the cosmos - deep into space and out the other side, really. But that day its wild intergalactic journey actually served to root me more deeply in the landscape I was exploring. I remember the broken chalky earth where the badgers make their sets, the dew pond with its looping swallows, a lonely bench pointed at nothing where I sat in silence for a space of time that was maybe twenty minutes, maybe an hour. I was learning, all the time. Over the course of that morning ramble I learned afresh how to be in nature. And this is exactly what Paradise Marsh teaches. It’s a small game, but also a gigantic one: truly a Stapledonian trick of time and space. I load it up and explore a colourful endless wetlands, cycling through day and night, spring, summer, autumn and winter. There’s an objective of sorts - I’m armed with a net as I plod around and I have a book of creatures to capture - but it’s an objective I have not really focused on for the most part. Instead I wander. I watch and listen, I see the different shades of the sky as it moves from peach to strawberry yogurt to dark bubbling storm clouds. I enjoy the rain one moment and the snow the next. I enjoy the silence - my silence. This gets to the heart of it, actually. Normally when I play a game, I am filled with words: I am pondering how to write about it, how to get into it, what I might say about it. The gift of Paradise Marsh, I reckon, is the silence it brings. I played in a kind of cheery fugue, if such a thing is possible. The room had disappeared along with the noise of the road and my cat asking for dinner. Then I loaded up Google Docs a few minutes back and realised I was still wordless and empty headed, and that this space and silence in the head is what the game had given me. So now I have to construct the experience from memory - I get to play Paradise Marsh twice. I can tell you that in the game I walk around this fuzzy landscape - at times, the entire thing looks like it’s been rendered with those huge wet markers you get at Bingo - and the game reveals itself as a series of happy discoveries. The trees change from oak to pine. The sky darkens or the sun rises and stains the world a lurid Tango orange. I pick a direction and move from water to earth, water to earth, and come across a pile of stones I might skip over the surface of a river, or a bottle filled with a poem. The landscape repeats and jumbles. I can never get to the end of it, but like one of those old Tom and Jerry cartoons I move past familiar things quite regularly. The landmarks cycle: a tyre swing, a moss-speckled windmill, an old tractor half eaten up by grass. There is always a touch of dereliction, human stuff giving way to the inevitable. An overhead light will flicker and I’ll only see the flicker when I compare it to the clear beam of the god rays lancing through clouds. A bin will be surrounded by rings of scattered trash, pulled out and discarded by birds perhaps. The game’s distinct spaces play into the animal catching stuff: moths appear at night but like a light source. Tadpoles stick to shallow water. The animals make noises and shapes too: I have been lured to them by a sparkle on the horizon and a chirp or chime. When I catch them, the thrashing connection of the net is almost jarring in such a quiet space. And we’re back to Stapledon, I think: the animals I collect eventually become stars and constellations that hover over me as I continue to explore. A nice distraction, but the game’s appeal lies elsewhere. The more I play the more I realise that I would dearly love to visit Paradise Marsh in real life. In the game, at least, I can linger for days and weeks due to the accelerated passage of day and night. This is a game about nature and about us. It’s about what nature gives us and what it asks of us - about what it draws out of us while we are present, and leaves us with when we have gone away.