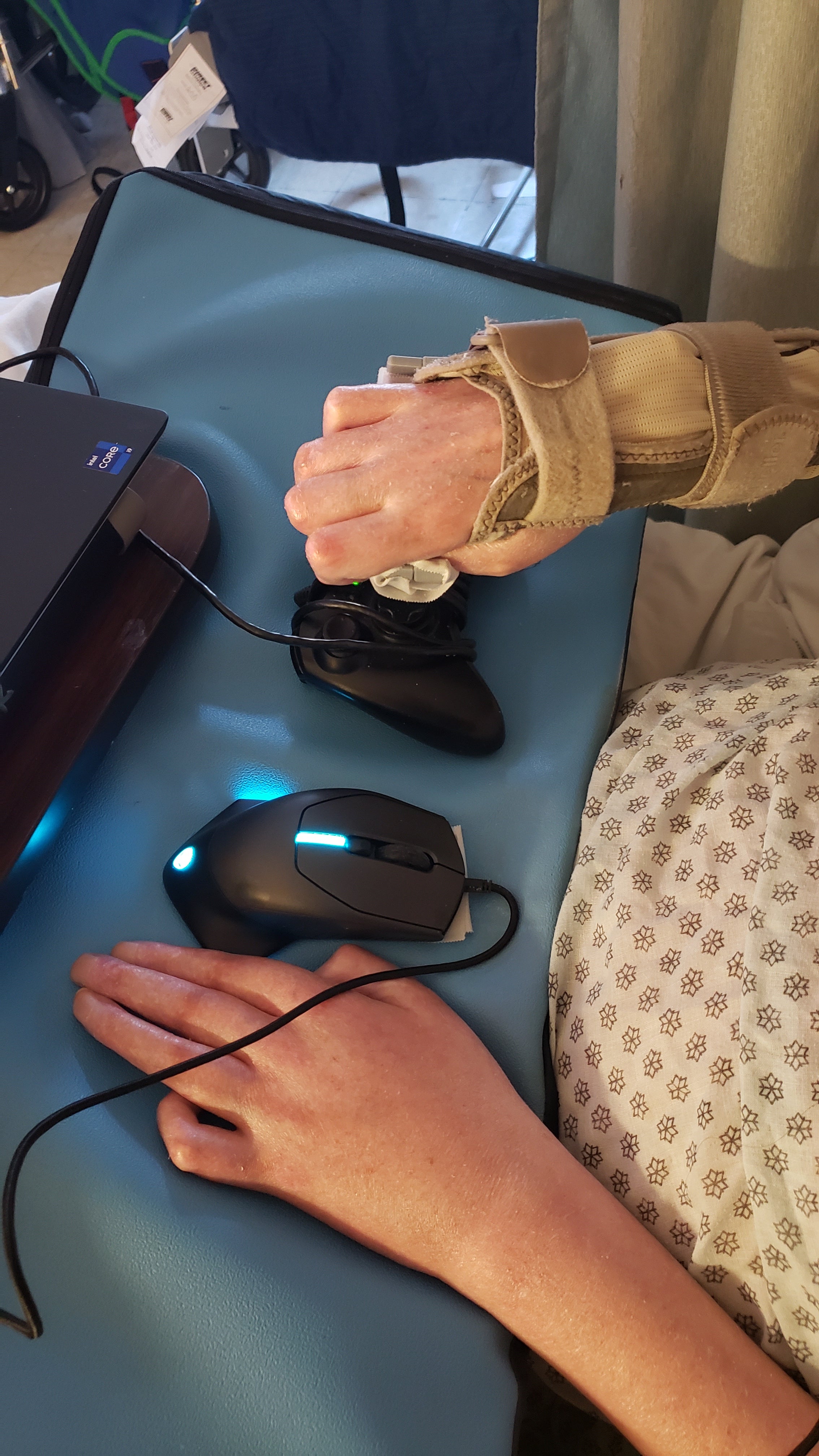

Kraft’s charity, The Controller Project, creates free downloadable blueprints to modify established controllers such as the PlayStation 5’s DualSense or the Nintendo Switch’s Joy Cons for players with disabilities or limb differences. In addition to this, it also uses 3D printing to craft these modifications and send them out to those who need them. Talk about nominative determinism. The Controller Project all started 10 years ago with a young boy named Thomas. “I first heard about Thomas through my wife, who is a teacher,” Kraft tells me. “He has muscular dystrophy, and this was impacting his ability to play Minecraft - something he loved.” At this point in time, Kraft was looking to generate interest for a site named Hackaday, which focused primarily on electronic projects. Kraft saw Thomas’ story as a good opportunity to pull in some traffic. He was already tinkering and building things as a hobby anyway, so if he could make this boy a custom controller, this would be an easy way to get some eyes on the site. “Now I know that is an incredibly insensitive and horrible thing to do,” Kraft admits, “but at the time, I just thought ‘hey, you know, it tugs on the heartstrings, it’s a good project, and it helps us get out there - I’ll make a video of this’.” However, when Kraft went to visit Thomas in his home, his attitude changed. “I saw the reality of the situation [and] it really impacted me,” Kraft recalls. “I felt a huge need to help in any way that I could.” Following his visit to Thomas’, Kraft began making his first custom controller, and he has been doing it ever since. “I kind of consider Thomas to be a successful failure,” Kraft tells me, smiling, noting that his first attempt at a modified controller certainly wasn’t his best. “I don’t think I really helped Thomas… but [the experience] launched the whole core concept of what The Controller Project is, and what was needed.” “Typically the accessories or custom stuff that [people] need are prohibitively expensive, and not covered by things such as insurance in any way,” Kraft continues. “And these are people who, typically, are struggling to have earned income [and] spending most of their money on things for other aspects of their disability. “They don’t have the money to spend thousands on a custom input device to be able to play games, even though it could be psychologically impactful.” In the 10 years since its conception, The Controller Project has recruited over 100 volunteers across the world who use their time and skills to come up with new customisations and, when required, print off the necessary pieces needed to modify a controller. For those already with access to a 3D printer, there is a whole catalogue of these modification designs available to download through The Controller Project, many of which actually offer very minor adjustments that just tweak a controller slightly. I am talking about simple, perhaps easily overlooked, modifications like a clip on attachment to extend a controller’s bumper triggers. However, even the slightest of adjustments can make a big difference to a player’s experience. Kraft says it is these types of designs, where the small customisations help make gameplay more comfortable for users, that have the widest user demand. “Even I have pain from holding a controller too long, because my hands are big and the controller is small,” Kraft says. “Just simple things such as a bigger grip to fit my hands properly would make me, as an able-bodied person, better able to play games.” The most basic (but by no means least important) designs in The Controller Project’s library are simple stands that hold a controller in place for the user at a specific height and location. This can be on a chair back, or even across a player’s leg. Then, at the other end of the scale, there are the modifications that completely remap a controller. Here, Kraft draws my attention to a design by engineer Akaki Kuumeri. Kuumeri has designed a modification kit that allows a controller to be used with a single hand. It straps to a player’s leg, with the motion from their leg then used to control the thumb stick. Meanwhile, thanks to an extension that gets clipped on across the top, this kit allows all of the buttons to be accessed on one side of the controller. This, Kraft tells me, is one of The Controller Project’s most requested kits. As well as Kraft, I also spoke to one of The Controller Project’s clients, Nate Passwaters. Passwaters only has use of his left hand, and previously played games using a modified PlayStation 4 controller. However, when he decided it was time to upgrade to a PS5, his previous modder was unable to provide him with the right kit for the DualSense. In a bid to find a new controller, Passwaters took to the disabled gamers subreddit, where he came across Kraft and The Controller Project. “[Kraft] took down my address, and a couple of weeks later I received the adapters,” Passwaters tells me, before expressing how much these adapters have helped him. Thanks to his new controller modifications, Passwaters says he can basically “play everything but FPS and games that have real difficult/complex button combinations.” Tyler Sandefur, meanwhile, is an occupational therapist who contacted Kraft after one of their clients shared their love of gaming with them. Several years ago, Sandefur’s client experienced a spinal cord injury that left him paralysed, a result of which means he is unable to use his previous gaming setup. “[My client] has the ability to turn his head up/down/left/right and has some use of his shoulder and elbow but no use of his hand or fingers,” Sandefur tells me. “We [started] hunting online for various adapted technologies that can be used for gaming. My client [told] me he used to use a joystick with a goal-post attachment to move a powered wheelchair [and] I instantly knew we could use an adaptive joystick to give him controller use for gaming.” After collaborating with UK based company OneSwitch, Tyler and his client were referred to The Controller Project. When they told Kraft what they wanted to do, Kraft immediately “jumped on board” to help. Kraft made Tyler’s client three 3D printed joysticks (two for a regular controller and one for an Xbox Adaptive Controller), which he sent to them for free. “Now my client is able to control a mouse cursor on his gaming laptop thanks to Caleb,” Sandefur tells me. In addition to these controllers, Sandefur’s client is also using head-tracking software that allows them to use head movements for keyboard controls. “We have a long way to go but I plan on setting up a custom configuration using the Xbox Adaptive Controller so that my client can have the ability to reach any button he needs so he can play any game he wants, at an elite/competitive level,” Sandefur says. “This is just the beginning.” It is evident that The Controller Project’s work is of huge importance to the gaming community. However, despite his clear passion for what he does, Kraft’s charity is confined by time constraints and finite financial resources. “A big holdup is time, either time for me to 3D print these things [some modifications can take up to eight hours to print] and ship them, or time to manage volunteers. I have volunteers all over the world. But emailing back and forth with these volunteers and trying to maintain quality and stuff takes time. And again, with my full time job and my family, I don’t have enough time to increase this,” Kraft says. “I think I could do 10 times more if I could do this full time. But I can’t afford it… I can’t afford to hire somebody even cheap to do it full time for me. So yeah, I mean, that’s the hang up.” This immediately begs the question, why has it come down to volunteers to cater for such a wide market in the gaming industry. Surely the likes of Sony, Microsoft and Nintendo should be doing more. After all, as much as Kraft tells me he would love to be able to help more people, he also feels it would be “beautiful” if The Controller Project “wasn’t even necessary”. Kraft believes a lot of the big companies just “don’t see the demand” for these modifications, and “they don’t yet understand that the demand - it’s growing!” “There is a huge demand for these features, even for people who don’t identify as having a disability,” Kraft says. “[People want] features that make things easier to use, or more pleasant to use,” he explains, recalling a past survey that revealed if subtitles on TV shows were left on by default, only a small percentage of users would actually opt to manually turn them off. This is something Kraft suspects carries over into hardware more than many may realise. “I know it’s not scientific, but if you just ask around your friends and say, ‘do your hands hurt after you play for a while? Does your thumb ever get sore from mashing the buttons? What would be more comfortable - if maybe the buttons were moved over a little bit?’ Your friends would probably say, ‘Yeah, it’d be great,’ even if they don’t identify as having a disability.” Kraft says he would love to see a big company such as Microsoft take what he is doing with The Controller Project to “the next level in organisation”. “I think it would be incredible to see an online configurator, where you can select from a group of parts and build out a 3D printed kit for your controller that does what you need, and then have it printed and shipped to you,” he shares, saying he believes something like this would be “extremely powerful” for consumers in general. “Again, I suspect there’s a huge demand for small modifications, little things like the triggers being extended up so you can get to them from a different angle or what have you,” he elaborates. “These are things that these companies could produce very easily, then you could have an online configurator for it all.” My time learning about The Controller Project has been eye opening, and I am so grateful to those that took the time to share their stories with me. If you would like to hear more about Kraft’s work and The Controller Project, you can find out more through the charity’s website here.

.png/BROK/resize/690%3E/format/jpg/quality/75/image-(242).png)