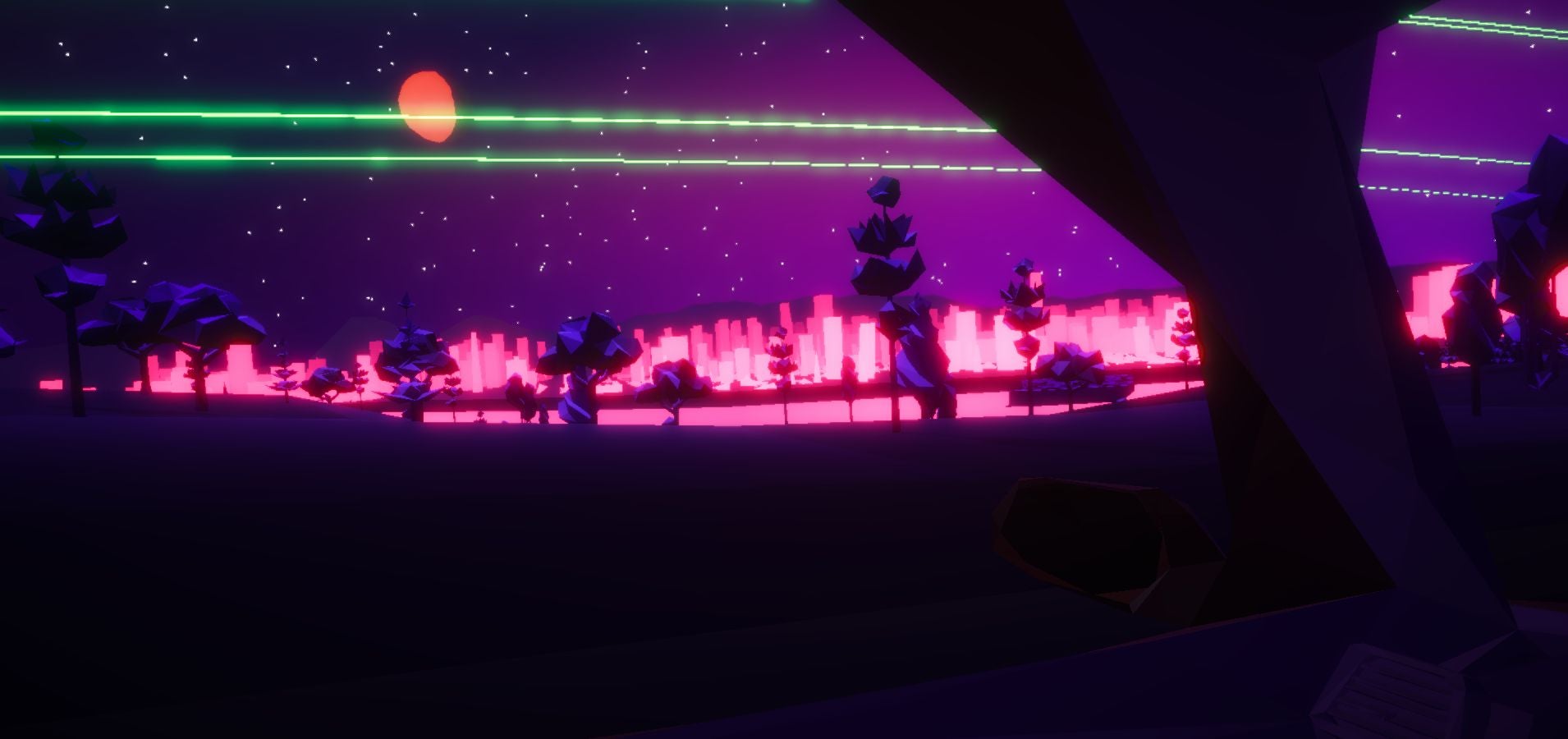

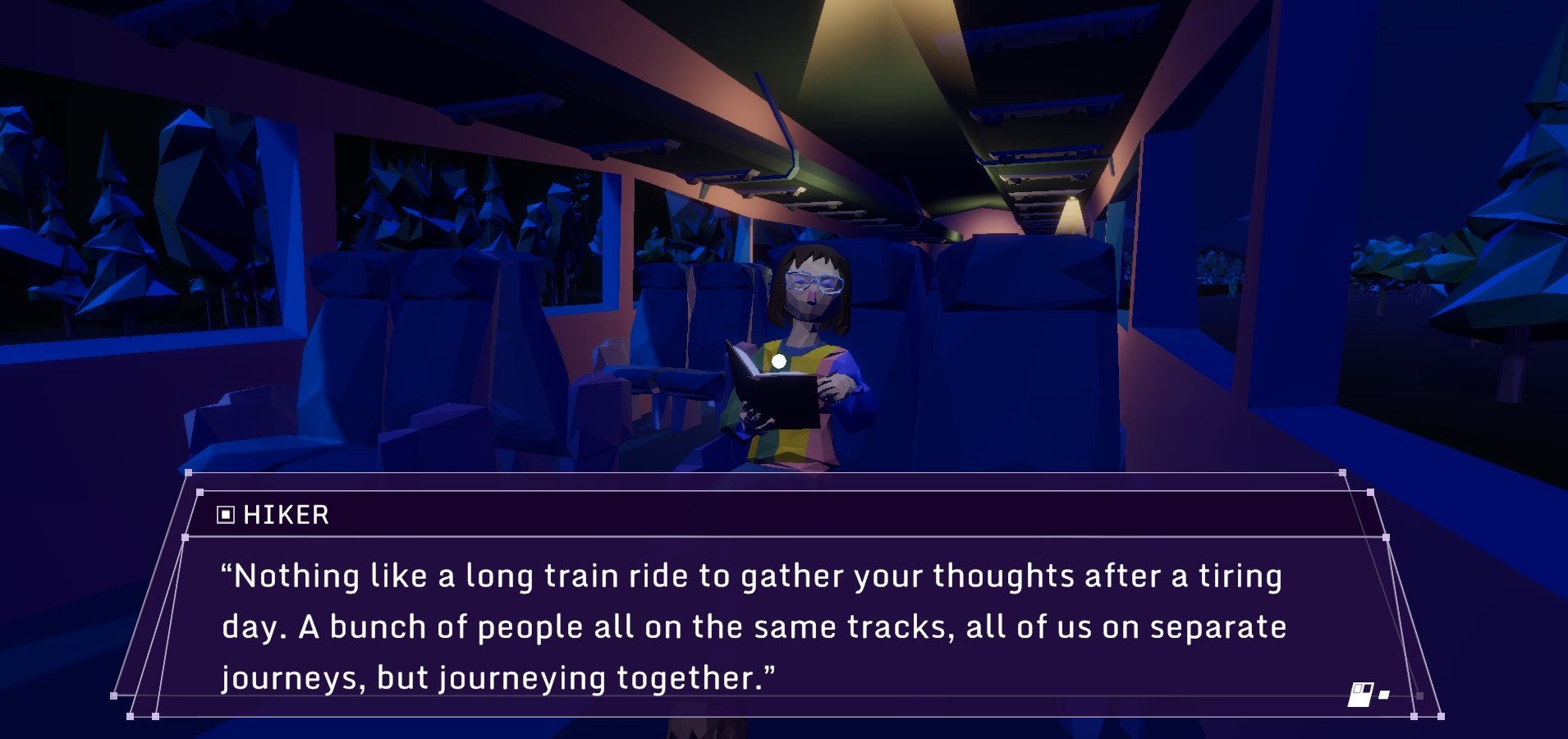

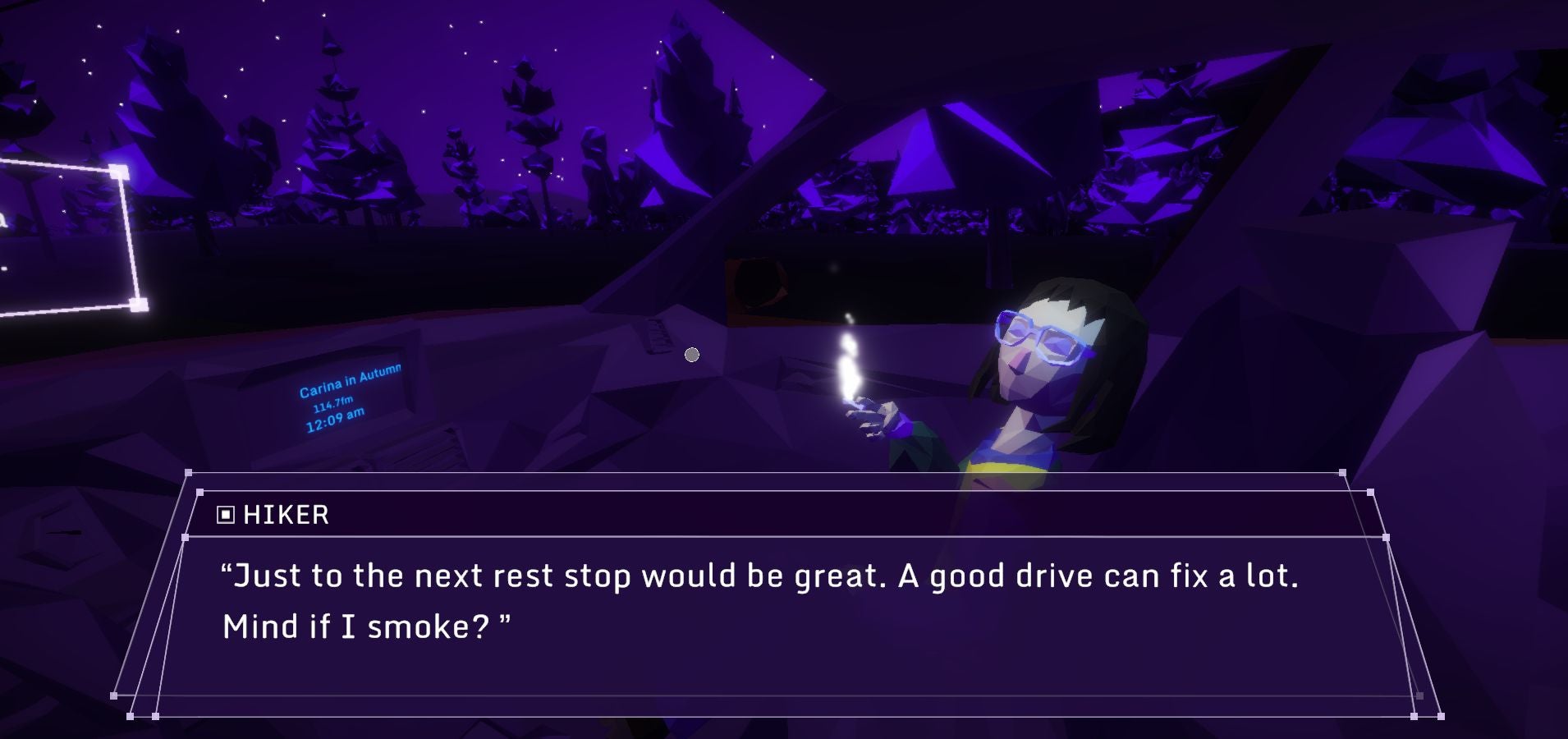

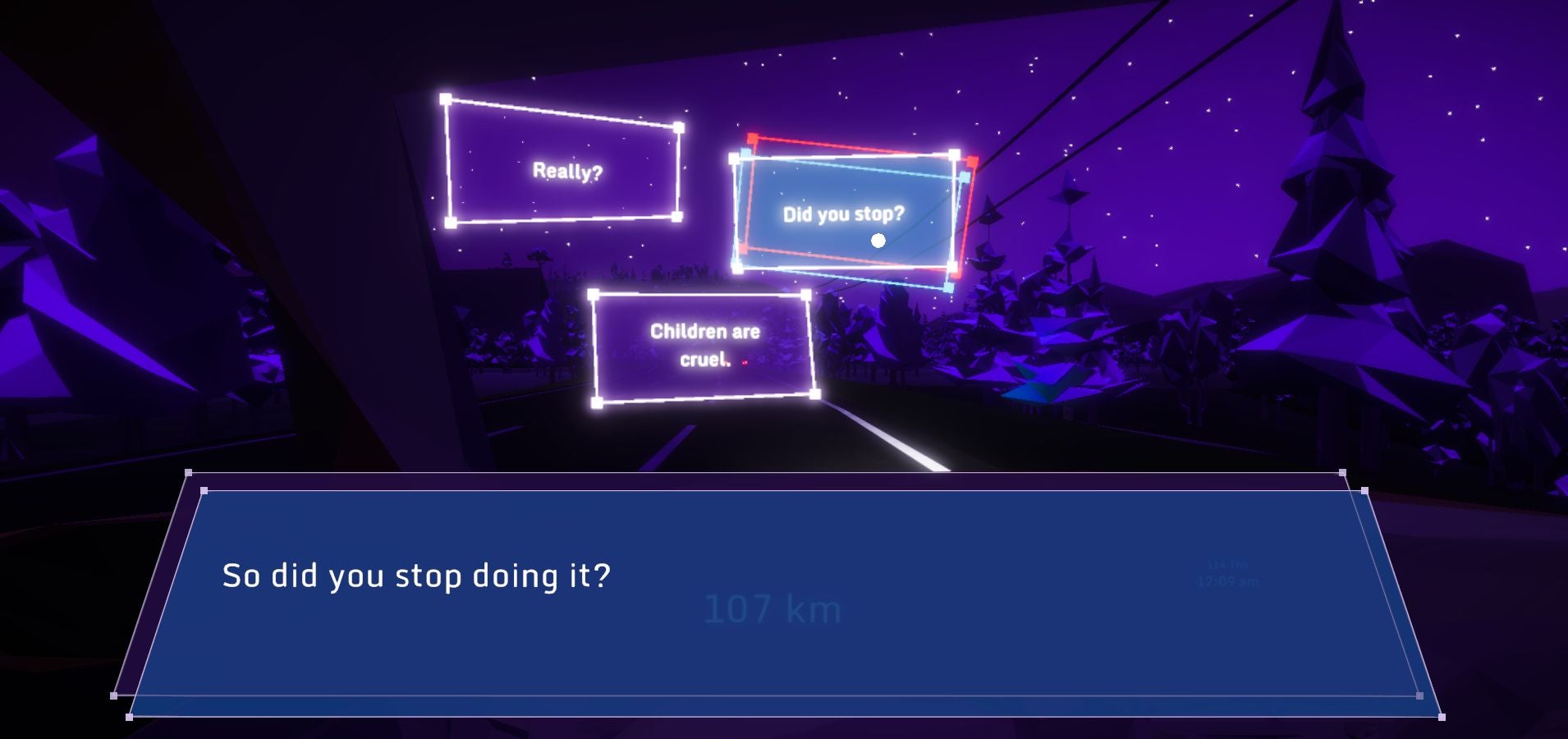

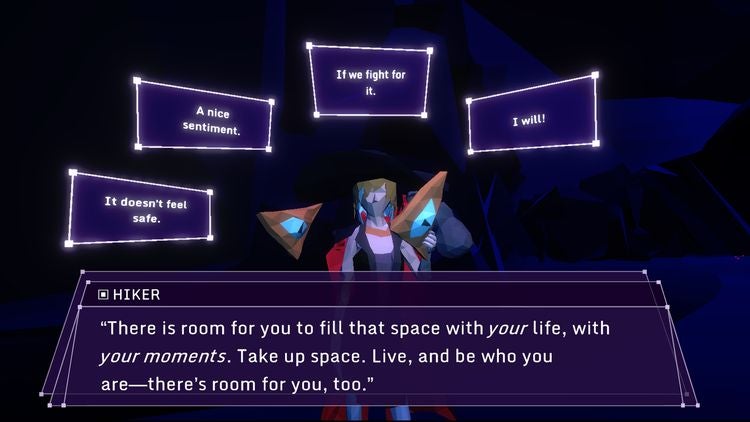

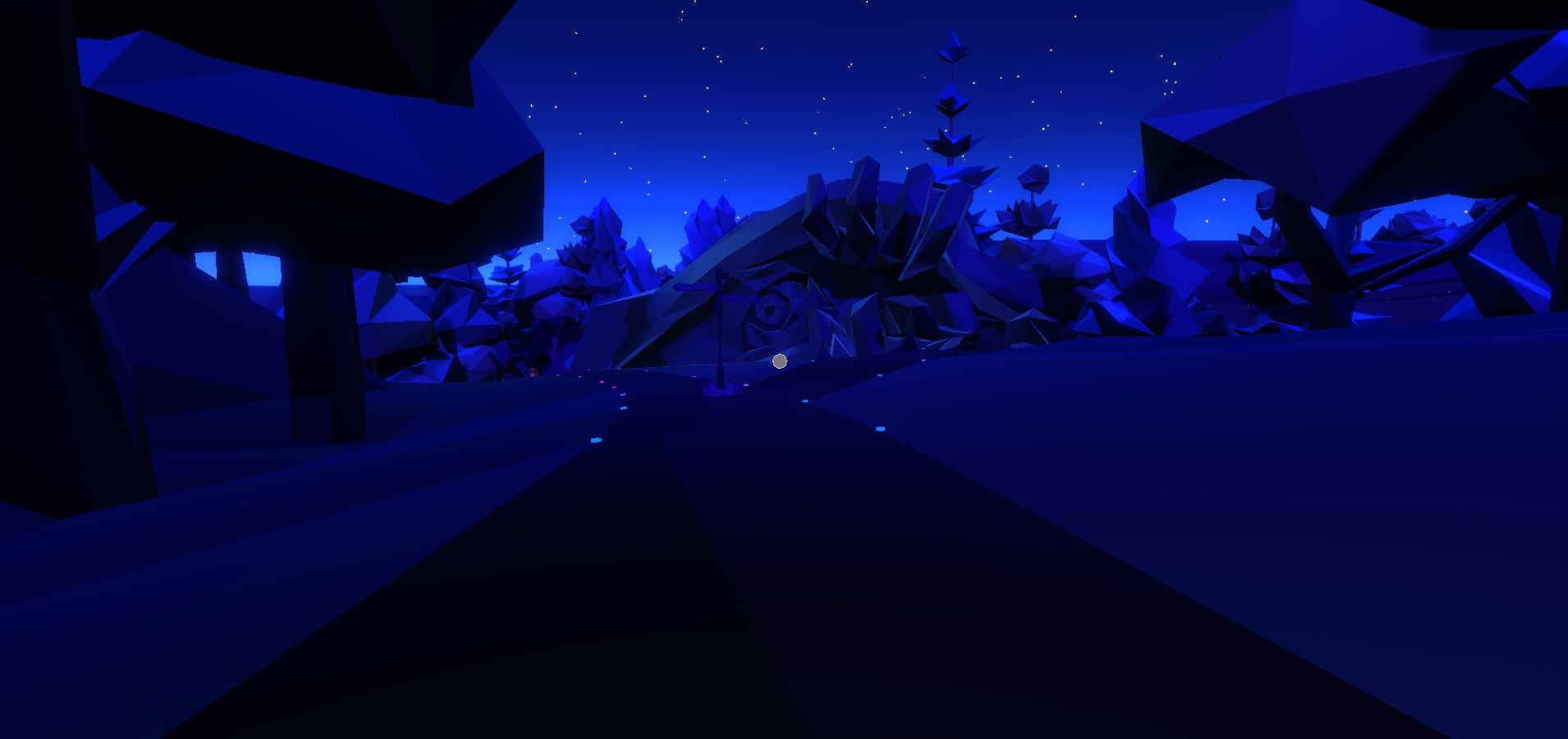

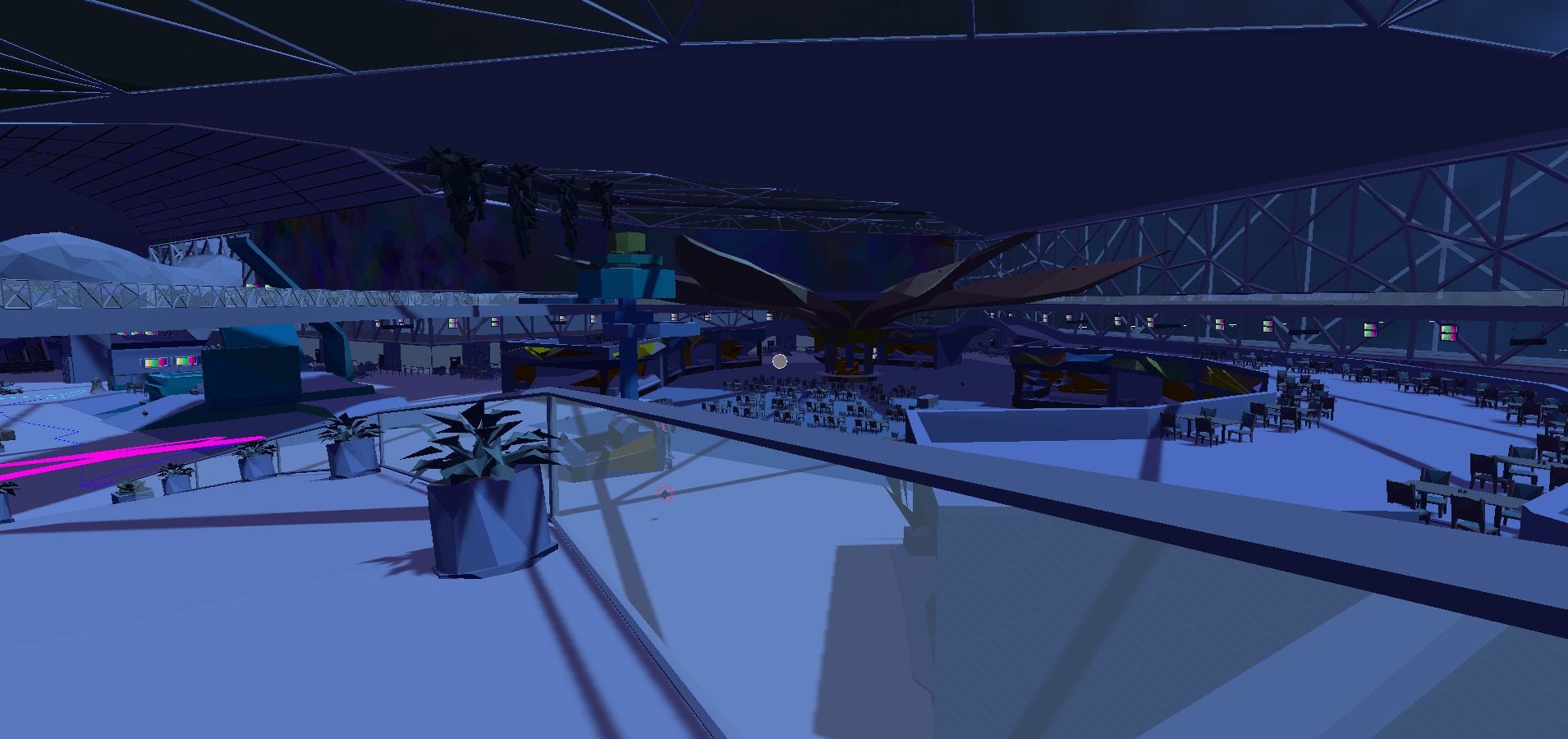

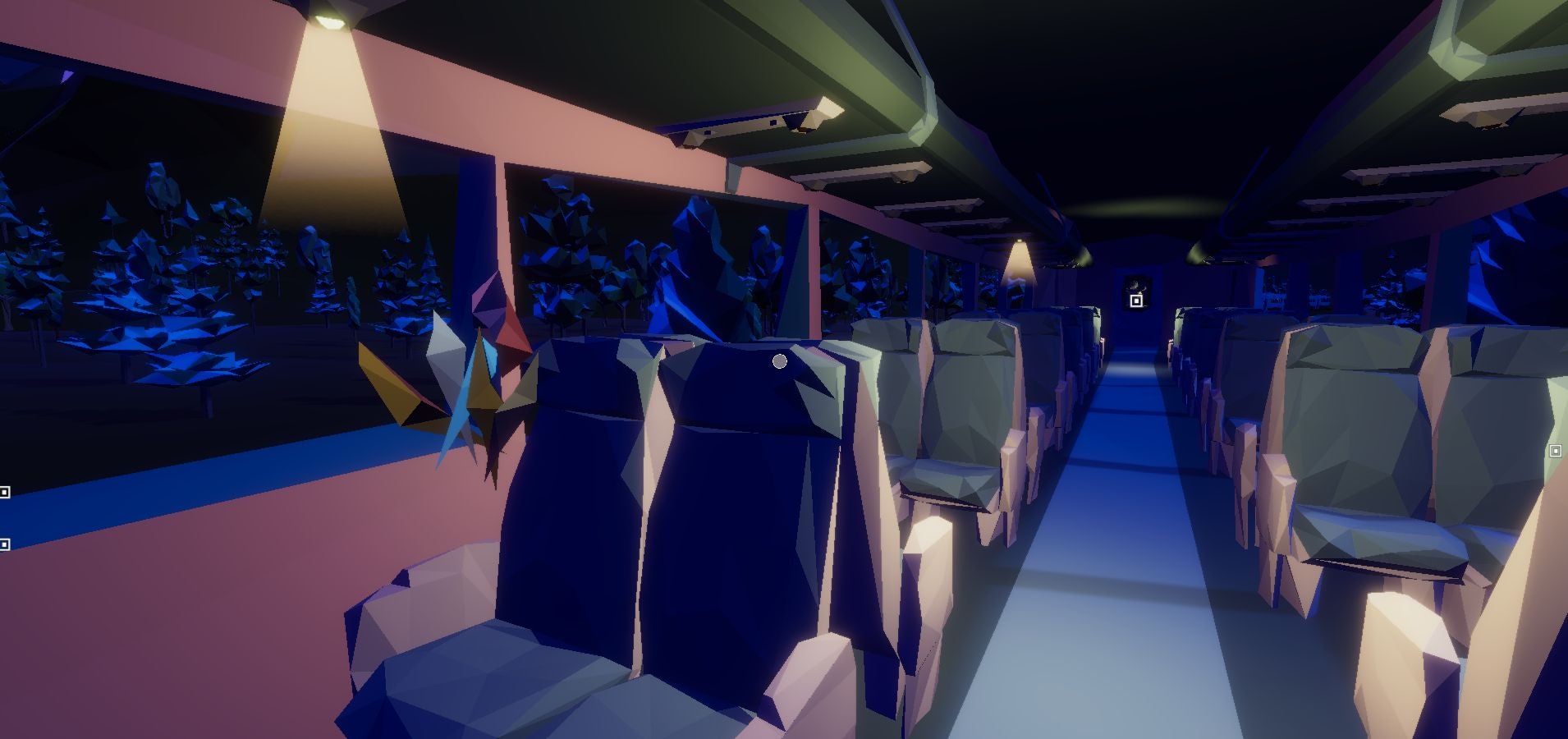

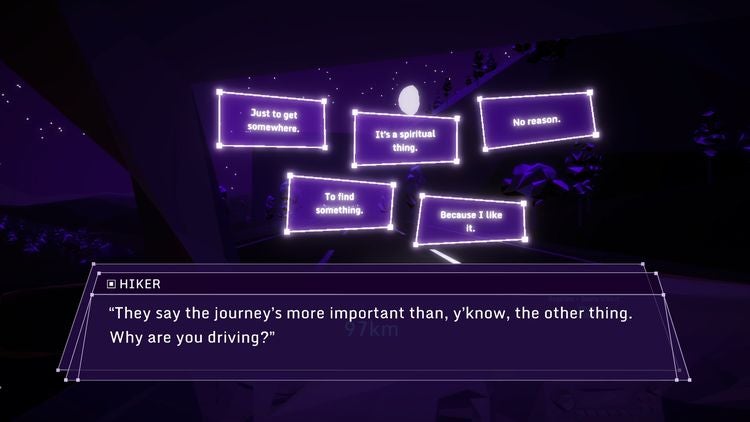

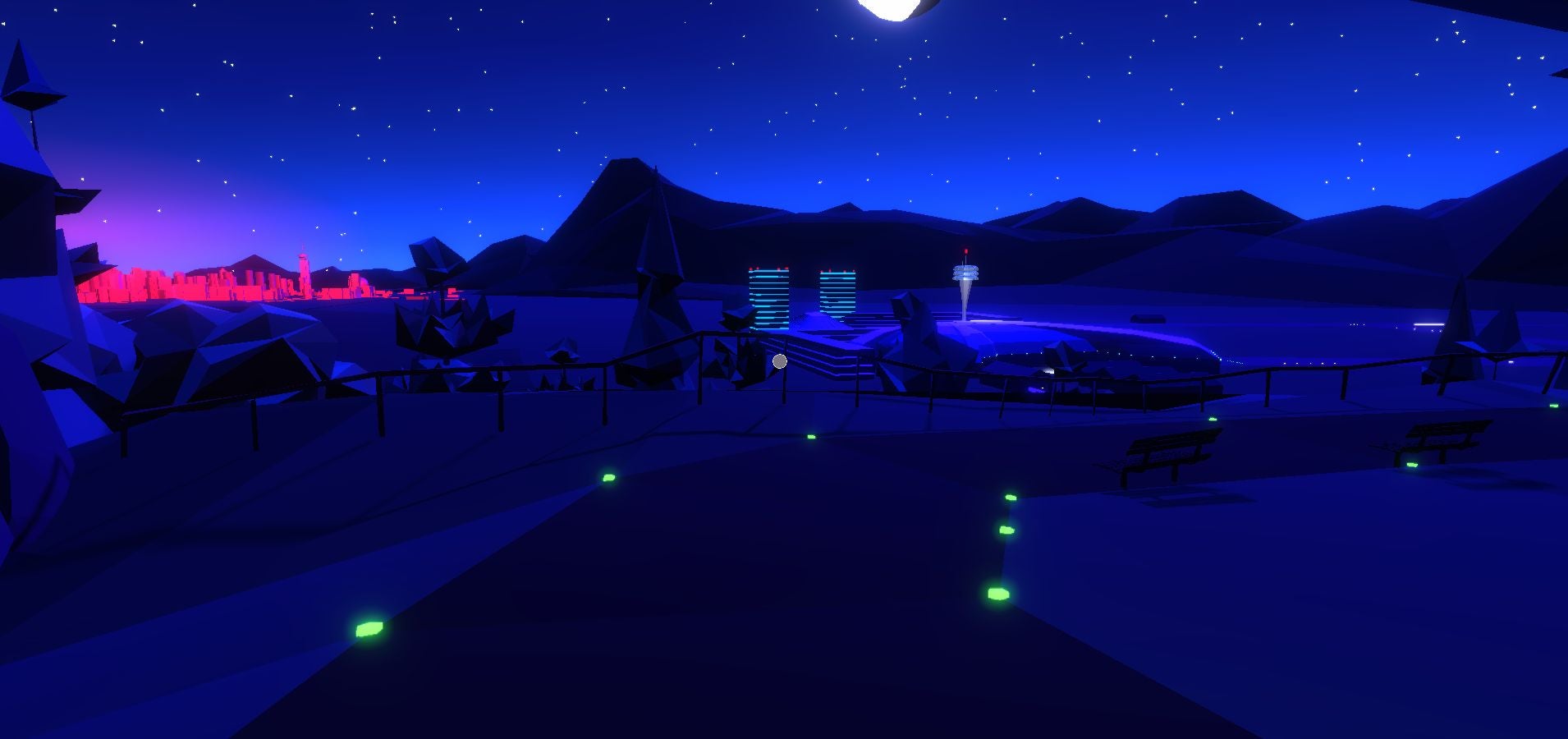

Glitchhikers: The Spaces Between is a follow up to developer Silverstring Media’s 2014 title Glitchhikers: First Drive, and it captures the experience of the late night solitary journey, where reality seems to shift into the otherworldly. Expanding on the late night car journey from the original game, The Spaces Between takes you to an airport, on a wander through a park and a train. Throughout your travels, you’ll encounter hikers who engage you in conversations covering subjects spanning personal stories to discussions about fate and whether our lives are predetermined. Last month, I spoke with Lucas Johnson, founder of Silverstring Media and studio director, and Claris Cyarron, co-founder and creative director, about the development of The Spaces Between. We started by discussing the inspiration for the Glitchhikers games, before exploring how they expanded upon the concept in The Spaces Between and captured the game’s ethereal tone. Afterwards, we moved on to the conversations you have with the hikers - touching upon the writing process, chosen topics and the importance of including queer stories - and how they explored the concept of space, particularly liminal space, within the game. Where did the inspiration for the Glitchhikers concept stem from? Claris Cyarron: The inspiration came from our Technical Director ceMelusine - who also goes by Phil. This was in 2013 and the turn of New Year into 2014. We sat down and Phil wanted to make a game about driving alone late at night. We started talking over beers and it turns out each of us had a lot of experience driving alone at night. I suffered from insomnia a lot as a teen and when I couldn’t sleep, but wasn’t too tired to drive, I would drive and listen to the late night radio and pick up breakfast from some all-you-can-eat-drive-through and enjoy the night. We wanted to make a game that captured the experience we’d all had and figure out the intersection between our shared experiences though we were in different places. Lucas Johnson: So that became the core of this idea of, no matter what we were doing, we’re making a game about driving late at night. There were key elements to that like the weird music on the radio which only plays at two in the morning on NPR or the conversations you have are the kinds of things your mind wanders to when it’s the middle of the night - life in the universe, the afterlife and other things. We then took that idea which was for Glitchhikers: First Drive that we released back in 2014, which became the seed of the Glitchhikers: The Spaces Between. We had this idea, a lot of people really jived with it, but not everyone had this same universal experience of driving late at night. We would pitch the game and some people would be like, ‘I’ve never really done that. I don’t really drive.’ And we’re like, ‘Right, there’s other aspects of this concept that are rich for exploration.’ There was always this opportunity to expand on the game and we had that the last couple of years with what became The Spaces Between, which takes that same core ideas of the late night journey, weird thoughts and conversations you have in those liminal spaces to not only the highway, but also a train journey, an abandoned airport terminal and a walk in the park late at night. When it came to developing Glitchhikers: The Spaces Between, what aspects of First Drive did you want to delve deeper into? Lucas Johnson: We really wanted to keep that core concept of every choice strengthening the experience; we wanted it to sound like you were in a car, we wanted it to feel like you were in a car. For instance, in First Drive, you don’t have full control over your car - you can’t drive off the road like in Grand Theft Auto, because, in real life, you don’t do that. It’s this automatic process of driving and zoning out, so we don’t give you that much control. When we looked at the other journeys we wanted to explore in The Spaces Between that was the core philosophy we had through each one; no matter what it was we wanted to ensure we were exploring what that kind of journey was like and they’re all a little bit different. So, in the train, you can stare out the window for a long time, go up and down the train or get off at a stop instead of riding to the end of the journey. All these little things that we did to push those ideas forward. Claris Cyarron: Beyond trying to capture the late night ennui, soul searching, sense of travel and the quality of those spaces, there’s another notion that was very central to us from the First Drive days all the way through and that’s liminal space and the Gothic sublime. Looking at the monstrous hugeness and unknowable qualities of the universe and seeing that as beautiful and majestic instead of terrifying. The mixture of terror and grandeur and awesome, in the classic sense of the word, is something we’ve always channelling. That’s often through the conversations with the hikers, as well as the voices of the journey; it’s not always a radio DJ who’s talking to you, it could be a podcast in the park or the overly friendly train conductor. But this sense of liminality, this sense of holding space for the thoughts you have when your mind is free to wander, it’s become a lot more popular. One of the things that surprised us a lot is how prevalent discussions of liminality and how things like Liminal Space Bot have gotten super popular. There’s something that was really universal, like we had all these big concepts, and we threw some stuff at the wall in First Drive to see if it worked with a small experimental game. It got a lot of positive feedback and, more than any of our other projects, people kept telling us about it years later. We kind of had the idea that was possible with what we were toying with, but we weren’t really sure if we had the formula right. The fact that people responded that way to First Drive indicated that we were on to something. Both Glitchhikers games have a very ethereal tone - how did you capture that feeling? Lucas Johnson: A big part of that has to do with the music. We worked with the same composer - Devin Vibert - in First Drive that we’re working with now and wanted to push the idea of the weird music NPR might play late at night. It’s experimental - sort of electronic. A lot of it is made by recording something, ripping that audio apart, putting it through filters and then back together in different ways. It creates this soundscape, especially in the drive, of that ethereal feeling as you’re moving through space. We did very different things with the music in each of the journeys in The Spaces Between, because we wanted each one to have a different feel to it. Glitchhikers as a whole is ethereal dreamy and The Spaces Between still captures that, but the train journey is meant to be more about community. This metaphor that you’re all going in the same direction together when you’re on a train with other people, so the music there is more folk-like. On the walk, the songs have more of a beat to them, because it’s about the driving motion of putting one foot in front of the other. Claris Cyarron: Another thing that was central to First Drive is there’s a lot of metaphorical resonance between what the game is doing, game design and narrative design in general. The basic structure of the drive: where you have conversations and answer questions to determine what happens next, ultimately getting to the end and having a fork path. The way you are making these choices is set up formally and structurally similarly to how stories generally flow in games - with these deterministic branches - we wanted to heighten that a lot in, for example, the park. So there’s different branching paths and you have the choice of which way you want to go - meeting a ton of nexus points as opposed to just one at the end in First Drive. Lucas Johnson: That speaks to the actual conversations and that’s another element of this ethereal feeling - these characters that appear out of nowhere and have conversations about the end of the universe with you, then disappear again. That’s core to the experience as well and, like Claris said, it’s these conversations about esoteric topics, the cosmic sublime and all of these kinds of things, but also topics that are very real. The first new conversation I wrote for The Spaces Between was ostensibly about an animal known as the Red Hand Fish, but, ultimately, parts of it were a metaphor for living with COVID as I wrote it in the summer of 2020. The idea of living behind glass and not being able to go out into the world - these are things we’re all thinking about. We wanted to be able to explore those things in this safe space; it’s a place where you can sit and think about these topics and the physical stakes are low, the mental stakes are maybe higher. On the conversations - the writing style has a very distinctive, often surreal, style and I was wondering what the actual writing process was like. Lucas Johnson: The beginning was thinking about what kinds of topics we wanted to explore. We only had six conversations in First Drive, there are 50 in The Spaces Between all told. We knew we had a lot of breadth to play with and a lot of things we wanted to explore different perspectives on; so there’s not just one conversation about life and death, there are several that come at it from different perspectives. Each hiker appears in three or four of the journeys, so we wanted the characters to not necessarily have a story arc to them, though a couple kind of do, but they’re always talking about the same kinds of things. One hiker will talk about death for multiple conversations, one talks about dreams and fate and we have a tree character that’s about nature and the balance of life and death. One thing that I tried to do is ensure every conversation had something that made it a little bit off. These aren’t just regular conversations you’re having with regular people - all of the hikers are a little bit weird. I wanted to make sure there was that element, because it’s that unreality. They’re not human necessarily, they’re teleporting into your car - were they there in the first place? Is this all a dream? These are things that we don’t answer and so we always wanted to make sure there’s some element of the conversation that’s like, ‘What did you just say? That’s a little weird.’ Claris Cyarron: Some of the characters are like, ‘I’m a psychopomp-type character. I want to talk about death and various vantage points.’ Other characters don’t talk about the same topics in each mode, but they have the same particular perspective. One character is a survivor of a lost legacy and everything they talk about is through the lens of what they’ve lost. They might be talking about their love of caves or about the history of their people, but everything is filtered through that. We didn’t want there to be a singular logic for all the characters. We wanted it to feel more like that random space your mind gets sent to where you could be thinking and talking with yourself or a random person on the flight next to you about anything. It’s the way that the silence - short, awkward, long - leads to small talk of, ‘Hey, do you ever think about the fact that every other person on this plane has a rich lived life? Cos I’m thinking about that now. That’s pretty weird.’ Lucas Johnson: Being able to take that story about one weird cave and see if we can make a metaphor out of it too. How does this apply to the bigger questions that we have, which is always an interesting take to have. Claris Cyarron: Something that defines a lot of our work right now is thinking about what the impact of games are and not just culturally or socially, though that’s a big part of it, but what’s the impact on the individual player. We’re talking about heavy subjects here, intellectual subjects sometimes, we want to make them approachable. We don’t want this to seem academic. We firmly believe that these big topics belong to everyone who’s ever looked up at the stars and been like, what does it all mean? Were there any conversation topics you wanted to explore in particular, because they range from philosophical musings to even the concept of space itself. Claris Cyarron: The concept of space itself is definitely something we wanted to talk about. Before games, I was an architect and that’s where my training and interest came from. It was both parts of that two word phrase - liminal spaces. Both of those were really important to us, we wanted to explore liminality and capture this transitional space and mindset. We also wanted to create a space for the player, hold space for the player and interrogate the ways in which games do that. Games often hold space for the player by being a wonderful escape, giving them this sticky thing they can mechanically understand and get better at, but you can also hold space by simply asking the player what they think repeatedly and hopefully help players hold space for themselves in a game. Instead of having the player engrossed by the game’s minutiae, you can instead have the game be a conversation with the player. How can you get into this mindset and then what can you get out of this mindset? We want games to do a better job at helping people find their way back out of them. Games are incredibly sophisticated at getting people myopically focused on them. I’m not trying to say that’s a bad thing inherently - we all love games and had extremely meaningful experiences with games, even when we’re diving into a massive 100 hour commitment, but not every game needs to be like that. Not every relationship with a meaningful game needs to be like that. Instead of the game just being focused on itself and what it can provide, it’s about being a catalyst for the rest of the person’s life. Lucas Johnson: Another big part of designing The Spaces Between was wanting to have it be a universal experience. We wanted anyone to be able to come to this and get something from it, even if that something is not what we intended necessarily. Our initial design goal with First Drive was we want you to have an experience and we don’t care what that is as long as you have one. So the universality which came from the late night drive a lot of people have experienced and wanting to expand that with multiple journeys, but, also, these different conversation topics - broad questions like life and death. We also wanted to have more specific conversations about things that are important to us and frame them in a way that they can be of interest to anyone. A big thing we wanted to make sure we included in The Spaces Between was more queer stories. Claris and I are both queer and that is very important to our storytelling - wanting to make sure we have that representation, we’re telling those stories, bringing in that for queer players to see themselves in this space and have these conversations, but also for other people to get that perspective. So we have several characters that are queer in various senses; some are explicitly queer, having same-sex relationships, but also queer in the sense of being different and bucking against the heteronormative patriarchy. Another we were very happy to include, partially thanks to the wonderful consulting firm, is a character who uses a wheelchair. They have three different conversations - all of them touching on their disability because that’s part of their identity, but, of course, they’re not defined solely by that disability. They’re an artist and have travelled the universe. It was really important for us to show these other kinds of conversations and maybe help people understand the perspectives of others. Claris Cyarron: We don’t really have the queer hiker. We have a bunch of queer characters, or disabled characters, who are talking about whatever they want to talk about, but it’s always filtered through that perspective, so it can come up and you can ask them questions. None of our queer characters talk like: you meet them in the train, queer conversation. They have rich lives which aren’t entirely defined by that identity, even though it helps filter their perspective. It’s about how can we push past that sad middle stage and into the real truth of the matter, which is that queerness is just one of the ways our life is defined. It’s an axis of oppression, an experience that helps focus and shape our lives, but doesn’t entirely define it. The way these interests and identities phase in and out of these conversations as you get to know these hikers is something I’m really proud of. There’s a lot more space for personal questions and getting to know these hikers as entities with rich worlds, perspectives and emotional states. That’s something I’m also really proud of, because the risk of making these hikers surreal, weird, and glitchy is they become divorced from ourselves. We always tried to strike a balance to make them feel human and relatable in the ways which matter to the player, while also making them strange and otherworldly to spark a sense of mystery and uncertainty. You mentioned liminal space earlier, and, in The Spaces Between, you explore more than just the car - you have a petrol station, you’re on a train, you’re in the airport. What attracted you to working within liminal space? Claris Cyarron: We stumbled on the idea partially in terms of trying to figure out, how are we going to make good on this? We had three different road trip experiences back in late 2013, how are we going to not tell those stories and, instead, capture all of those experiences. We were groping towards this idea of liminality, but I don’t know if that was actually something we were talking about until after the game was released and it’s experimental, ‘Let’s see if this works,’ worked. Okay, why did that work? For years afterwards, I was kind of passively asking myself that question, but it stuck in the back of my head because it seemed to rely upon a lot of really big things that were just under the surface of my perception. I kept interrogating that and found my way to - we’re toying with liminality, we’re playing with this sense of transitional moments and mysticism. I ended up getting into tarot and secular magic partially as a way to explain why Glitchhikers worked so well. Through understanding how tarot takes all these different symbols in this loose structure, jumbles them up and then asks the player to make a story that makes sense - that game mechanic is actually quite similar to Glitchhikers. By the time we got around to having the skills, the studio and the funds to make The Spaces Between it was like, ‘Design it from the get go around that.’ One of the things that surprised me as an architect is, what does a restful, mystical, space look like? If you would ask me in architecture school, I sure as hell wouldn’t have been like, ‘It’s a car. It’s weird music on the radio, but it’s a car with weird music on the radio.’ I can’t help but see games as architecture as well as like entertainment objects - their spaces that we spend time in. Things like Facebook have proven that we can completely erase public space and, instead, give it over to companies and have them hold our public forums online. The blend between digital and physical space as far as a lived environment for communities to move through - the ship has already sailed - there’s no meaningful distinction as far as stuff is more meaningful in the physical realm versus the digital realm. I’m always looking at games and asking, what kind of space is that? We wanted to look at the car and go, ‘That mode still makes a lot of sense, even though it’s really stripped down.’ How can we make others that aren’t just copying that, but are meaningfully distinct to where they’re capturing, in their mechanical distinctness, the different aspects of the space. The classic example was the train, we were thinking about that from early on as a thing that we wanted to expand into - that sense of being able to move through this space while also moving is such a huge part of it, so really leaning into that was an obvious direction. Lucas Johnson: I can’t remember how much we were talking about liminality specifically with the first game, but that’s what we were ultimately creating. It was this transition between two places and liminality is really about that transformative moment. So we were doing it in First Drive whether we knew it or not and, like Claris’ was saying, really being able to lean into that with The Spaces Between. Being able to come into it and have an experience which will change you in some way, whether that’s very tiny or very profound. You’ve talked about being an architect - I was wondering, how did you approach designing these spaces, especially in terms of interweaving the architecture and the narrative you want the player to experience? Claris Cyarron: It depended partially on the journey. We talked a lot about how we wanted to move through space, what the hallmarks of that journey are and, once we had a basic template, it’s this question of where can we inject more architecture and interest? And blurring the lines between architecture and art objects. That’s something that games can always do, because, oftentimes, the best examples of architecture are the buildings you don’t go in, but are, instead, next to the place space you look at it from different angles. In the park, we have a sculpture area that was very fun to develop, because it was creating this sense of rolling hills, big open space and not having a lot of trees with this notion that, at particular nodes, there were going to be points of interest. Then having that space set up and working alongside our tech artist Bill Davidson to create these sculptures. Like, ‘Hey, I have an idea for a Richard Serra-type sculpture here,’ so we’re going to make that and check if it feels good to move through this space; is it screening the views to the other sculptures from the other side of the park? This is one small corner of the overall park, but, as far as that mode is concerned, that’s how we designed the entire thing. I did the basic concept for that space in VR on Tilt Brush and I was drawing sightlines from one point of park to another. It was like from this ridge, you should be able to see here, here and here, so I know that these are other overlooks you need to be able to see to get a sense of space and construct a mental map. In the airport, you’re inside the architecture, but, still, there’s smaller pavilions and buildings within this larger building, so really playing with that sense of life and cascading scale - large buildings, smaller buildings, even smaller buildings - in this Russian nesting doll vibe. Always keeping in mind that Glitchhikers isn’t a very mechanically intense game, but, from a design standpoint, it was something we were talking about a lot. How are you moving through this space? How are you interacting with this space? Lucas Johnson: It’s about the experience you have as you walk through and meet these characters, so we play a lot with randomness, but designed randomness. It’s the tarot metaphor Claris mentioned before - we wanted to create these spaces and put enough in that you could draw meaning from, but don’t necessarily. As you’re moving through the park, for instance, you might come across a particular topiary that’s like a bird’s hand casting a shadow puppet. At the same time that you come across this landmark, you might be listening to a particular song on your Glitch Pod which resonates with you and this shadow. Then, you have a conversation with one of the hikers that connects all these three things together. We wanted to create these spaces in a way that could allow for those kinds of connections. When I was playing the game, I loved how the conversation on the train was divided up into three instalments causing you to hunt down for the hiker. It led me to noticing that the conversations differ in topic and length depending on where you are - why did you decide to make this distinction? Lucas Johnson: It really speaks to wanting to make each journey a little bit different, so the structures of the conversation very much fit with, or are intended to fit with, the structures of the journey and the mood we wanted to get across in the journey. Being in an airport terminal when all of the flights are delayed in the middle of the night is a very purgatorial experience; you’re wandering around, there’s nothing to do, you’re just waiting. The conversations in the airport loop more than a linear conversation would in the way that an RPG conversation would - where you can go back to the same questions. So the conversations can take on this purgatorial aspect and they’re a little more meditative. Versus with the walk, where each conversation has a major branching point and you end up talking about the topic from a completely different perspective depending on the choice you make. The train has this community sense and so a lot of the conversations are more personal, because you’re in this community space. That’s where the three different, shorter, conversations turned into one longer conversation. We wanted to have a break between them, let you think about them before moving on, then use that as a way to delve deeper into the topic. Each one starts a little more surface level, then, by the end, it’s talking about something really deep - the reason I was talking about dreams and fate is because I have concerns about whether everything is predetermined. The mistake we made, as it turns out, was we weren’t making one game, we were making four games in one package, because each one has a lot of similarities, but also differences. Claris Cyarron: Our mistake is the players’ gain, so I feel super proud of what we’ve done. In the train, especially, we wanted this sense of having space for the player to think about what the hiker has said before you talk to them again, but also this ellipsis that implies they’re doing the same thing. This is a moment where we can humanise these characters. They’re not daily gods or powerful spirits - they’re strangers that have a perspective. They’re beholden to the same cosmic forces we are, even though they might seemingly have a better grasp or a more comfortable philosophical standpoint than we have in the particular moment. Also part of the liminal journey of Glitchhikers is the invitation to try things on; you don’t have to be, ‘I’m a starch existentialist and if I deviate from that, then my existential score will go down and people will respond to me differently.’ There’s no permanent punishment for going, ‘Today I actually don’t believe any of this shit. I want to push back on it and hear you talk me into this stuff does matter.’ In giving player agency about what conversations they experience, people have the opportunity to be like, ‘Hey, would love to talk to you random person. You’re thinking about your abusive former relationship?’ Well, not only do you have the ability to interrupt every single conversation, each hiker models good behaviour like, ‘I’m going to help you maintain your boundaries and not take up energy that you’d said you don’t have.’ You also have the ability to filter out entire types of content beforehand if you’re like, ‘My uncle just died suddenly and tragically. The one thing I don’t want to talk about is death or the one thing I do want to talk about is death.’ Then you can filter everything off but death to increase the chance of having those conversations. We want to allow players to tailor the experience, while still having it be defined mostly from generative randomness, defining meaning and finding patterns in that randomness. You make a choice, what kind of journey, and we randomly decide the music, hikers, etc. Then the choices you make are back and forth between you and the game as you construct meaning together. Maybe it’s because I’m from the UK and it’s already a very different driving experience - I noticed in the driving mode for both Glitchhikers’ games, you don’t have any contraflow traffic or any exit routes and was wondering why you made that design decision. Lucas Johnson: The exits for the drive were certainly drawn from First Drive where we wanted to have two or three conversations, not leave the highway necessarily until the end, and, same with The Spaces Between, you get this choice to exit the highway or continue driving, which doesn’t have any mechanical ramifications but potentially has some metaphorical ones for the player. We wanted to really highlight that moment in the drive and not dilute it with exits that you could take elsewhere. Contraflow traffic - I do remember there was a point part way through The Spaces Between when I was looking at the terrain we were generating and had the thought of, ‘We don’t have any counter flow traffic’. Often on a highway, the other lane might be separated somewhat - we don’t even have that. And I was like, ‘Should we do that? I don’t think we should.’ Claris Cyarron: Some of my favourite drives have ended up being kind of between Seattle and Vancouver. My favourite parts are where it’s separated by a big chunk of trees, so there’s this increased sense of solitude. There’s a couple of aspects of driving that really add to ‘This feels like driving’ and we very much elected not to do that. One is road noise. I’m extremely proud of the soundscape that we have in the game - A Shell In The Pit worked with us on it and they did an amazing job. Each mode has a really rich soundscape that doesn’t repeat often, so it really feels like a real space. But road noise, train noise - those kinds of things are so much louder and more intense than in the game. Similarly I feel that contraflow traffic - especially when you have cars coming on with their headlights - rather than try to massage that in a way which felt cohesive with the restful space we were creating, we realised it wasn’t going to add what we wanted it to add for that scope cost. Lucas Johnson: The loneliness and solitude of the drive is a key part of that and not having those lights flashing in your face as you’re driving. There are other cars on the road, but they are fleeting and you can never catch up to them. There’s also the surrealness to it; every mode has those little things that are just a little bit off, a little bit weird. There’s no counterflow traffic, why is that? In the train, you get to the front and you have a lovely viewing car where you can see the landscape ahead of you, until you realise that means there’s no engine on this train. So it’s those little things that we’re like, ‘Do we want an engine?’ No, it adds that element of - is this even real what you’re doing right now? If you’d like players to take away one thing from playing Glitchhikers, what would you like it to be? Claris Cyarron: It’s really hard to pick one bank - we are constantly moving through spaces and moments where magic and transformation is possible. Reinventing yourself in small ways, or in impossibly large ways, is something that everyone can do and is valuable. We often feel that we are fixed in these moments, in our situation and our lot in life, and I hope this game helps people realise that they’re always adjacent to the possibility for transformation. Lucas Johnson: Something that we’ve been thinking about a lot very recently, with everything happening in the world too, is that Glitchhikers, if we’ve done our job well, offers a space to reflect on the state of the world and on yourself. There are conversations that are very real about how do we keep hope in such a dark world that we live in right now? How do you keep that fight going? We want to make sure that it’s a place where people can come and maybe have the space to reflect when, again, we also live in a world that we’re caught up on our social media feeds and all of these things constantly doom scrolling. To be able to step away and take a breath and have some calm conversations about deep topics is something that we really strive for. At the end of the day, I still go back to what we said with First Drive, which was, as long as you’re taking something from this game, whatever that is, we have succeeded. Glitchhikers: The Spaces Between is currently available on PC, Mac and Nintendo Switch.