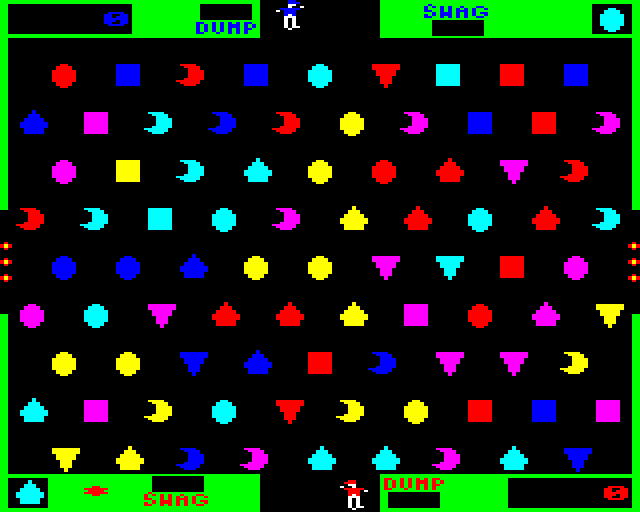

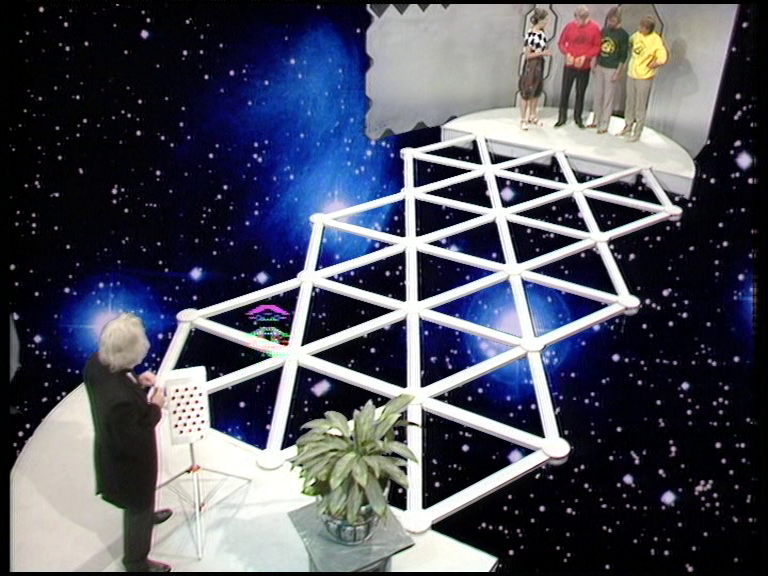

The Adventure Game was created in 1979 by veteran BBC children’s producer Patrick Dowling, who had previously delivered such era-defining shows as the summer holiday staple Why Don’t You…? and brought genteel artist Tony Hart to our screens in Vision On and later Take Hart. The idea came from his interest in Colossal Cave Adventure, the genre-defining computer game written by Will Crowther in 1977 for hulking mainframes, and the rising popularity of Dungeons & Dragons in the UK. Dowling was also inspired by the hit radio adaptation of Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and wanted Douglas Adams to write for his show, but production on the TV adaptation of his book made it impossible. The Adventure Game is best described as an early precursor to The Crystal Maze, an inspiration for subsequent shows like the cult classic Knightmare and a pioneering example of the now popular “escape room” concept. In each episode a trio of affordable BBC celebrities were transported, via the magic of chromakey, to the planet Arg where they are tested by the playful but gently sadistic inhabitants, the Argonds. These reptilian beasts occasionally appeared in their natural form, the sort of low budget monster outfit that kept Doctor Who afloat, but were mostly represented in human guise. One character, a cranky Argon uncle, preferred to only appear as that uniquely threatening aspidistra, shaking his leaves furiously at contestants thanks to R2-D2 actor Kenny Baker hiding in its pedestal and rolling it around on a child’s tricycle. The trio of adventurers would be tasked with a series of logic puzzles, progressing through a series of rooms before facing the terror of the Vortex at the end. Those who survived that ordeal were allowed to return home. Several recurring puzzles revolved around drogna, the Arg currency, consisting of a coded system of coloured shapes where the value depended on the number of sides multiplied by the value of the colour. Like so many aspects of The Adventure Game, this detail was left unexplained both for the contestants and the audience at home. A product of a gentler TV age, the show is still enormously charming but appears achingly slow to modern eyes. The contestants were left to work things out in their own time, resulting in lengthy sections of the show that involve nothing more than now-forgotten actors and presenters looking confused in long takes with few cuts. Most episodes include at least one occasion where one of the Argond characters has to join them, in character, and all but spell out what they’re supposed to be doing. Although Douglas Adams was unable to work on the series, there’s an unmistakable echo of his mischievous absurd humour running through everything. What is most intriguing when revisiting the show today is how similar it is in both construction and tone to the computer adventure games that would come later. A typical solution sequence might involve using a potato to retrieve a corkscrew to open a bottle to find a clue in semaphore that must be deciphered using a book hidden on a shelf. Many of the challenges set by the Argonds are recognisable now as the sort of arcane inventory puzzles that would drive classic 8-bit British games like Dizzy, Finders Keepers and Everyone’s a Wally. The Adventure Game also incorporated actual video games of the time into its format, with the last two series opening with Arg-themed versions of Asteroids and Space Invaders and some early episodes requiring the players to sit at a BBC Micro and solve a text adventure in order to progress in their actual physical adventure. As with the physical puzzles, these sections simply involved watching minor celebrities painstakingly typing in prompts and going around in virtual circles for minutes at a time. And within the “reality” of the show those Argonds themselves are, of course, now recognisable as quintessential NPCs, always on hand to flesh out the world and the fiction. They were the quest givers but also an ad-hoc hint system sent into the scenes by Dowling with heavy-handed nudges in the right direction if the contestants were making no progress whatsoever. The show even featured its own equivalent of an end boss, in the form of that terrifying Vortex. This was a chess-like permadeath final challenge in which the contestants took turns to try and cross a maze suspended in space. Approaching from the other side, invisible to the contestants and alternating moves with them, was a shimmering vortex effect. This peril could not move onto the spot where the player stood, but the player could - and almost always did - unwittingly step onto the space where the Vortex lay in wait. This being early 80s children’s television the effect was not fatal but just meant the evaporated player had to hitchhike home from deep space. Rewatching the show, one of the greatest pleasures for me - other than the chance to once again enjoy Graeme Garden from The Goodies and his magnificent sideburns - was seeing how the show evolved from series to series. This was not an era where TV shows - let alone children’s shows - were painstakingly polished and honed before launch. The first series, which aired on Saturday mornings in May 1980, was made up of half-hour episodes which meant almost all the puzzles were cut short, or their solutions garbled in the rush to fit everything in. For the second series in 1981 producer Patrick Dowling himself appeared onscreen at the start of each episode, now extended to 45 minutes and broadcast in the early evening. Dowling would welcome the contestants to Television Centre, then pack them off on a shuttle to Arg. Puzzles which had been opaque and confusing in the first run were either replaced or overhauled now, with more elaborate sets and the inclusion of former Blue Peter presenter Lesley Judd, a contestant in the first series, returning as herself in a recurring role as a saboteur whose aim was to derail her fellow humans. And so the show continued through two more series, returning in 1984 and 1986 with further iterations on what had worked - and what hadn’t - in the previous episodes. In other words, we’d now call this a game show that launched in Early Access and proceeded to playtest, iterate and bugfix its format even as it was being broadcast. Strangely, for a show so steeped in gameplay structures and tropes, and despite airing at a time when the British games industry was a thriving cottage industry churning out hundreds of titles, there was no official computer adaptation of The Adventure Game that you could play along with at home. The closest we got was Drogna, an obscure puzzle title for the BBC Micro based on that baffling alien currency. In the sort of dedication you likely wouldn’t see today, that game was personally coded by The Adventure Game’s creator and producer, Patrick Dowling. Like most vintage British shows, there wasn’t a lot of Adventure Game produced. Only 22 episodes across six years, two of which went missing from the BBC archives. Yet it made a lasting impression on a generation that was just being introduced to a new kind of play, echoing and foreshadowing computer games while only occasionally referencing them directly. At a time when the first home computers were arriving in UK bedrooms and coverage of games was vanishingly rare on TV, The Adventure Game offered a strange but vital conceptual link between the cosy world of old media and the rapidly arriving interactive digital realm.