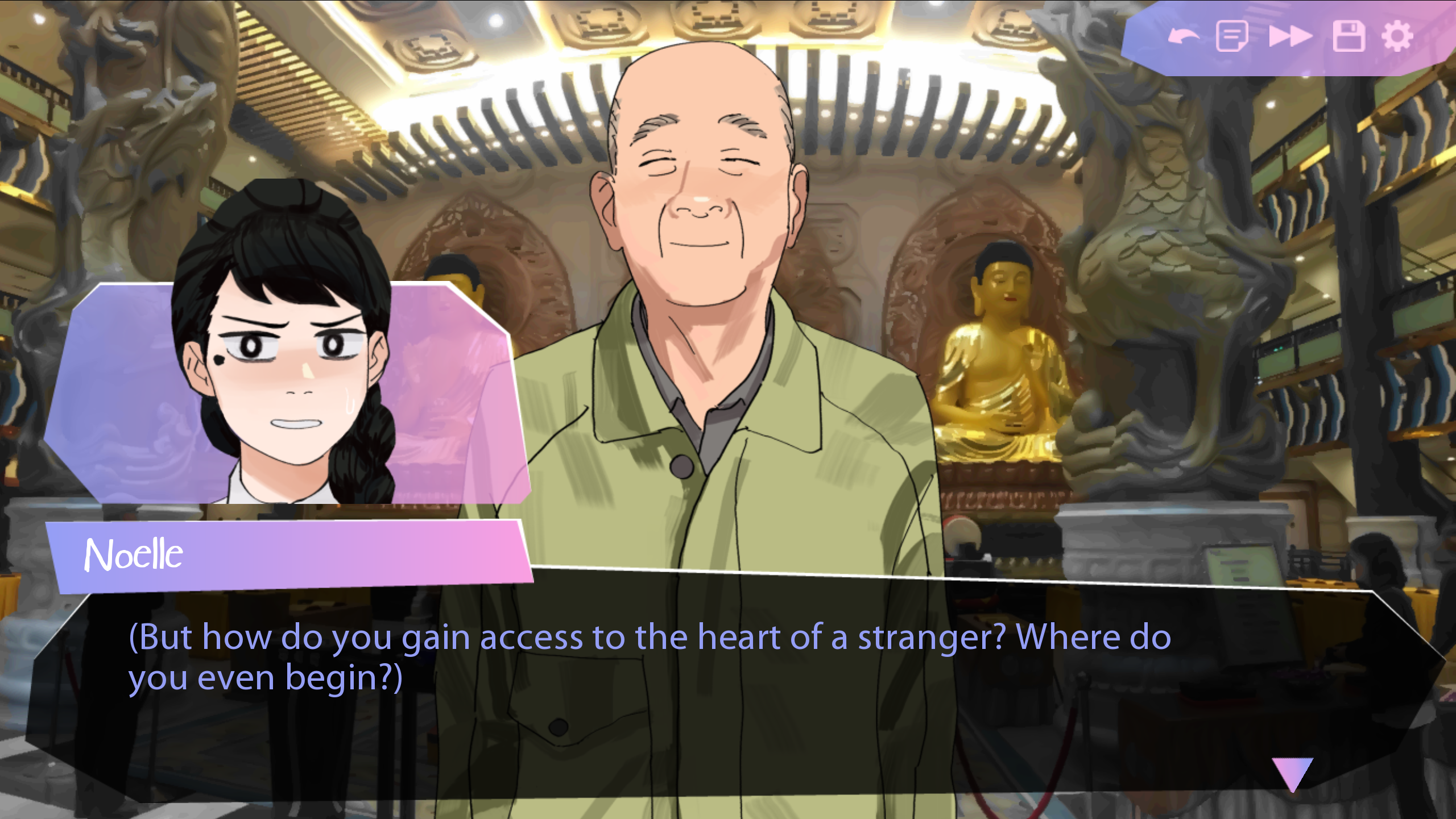

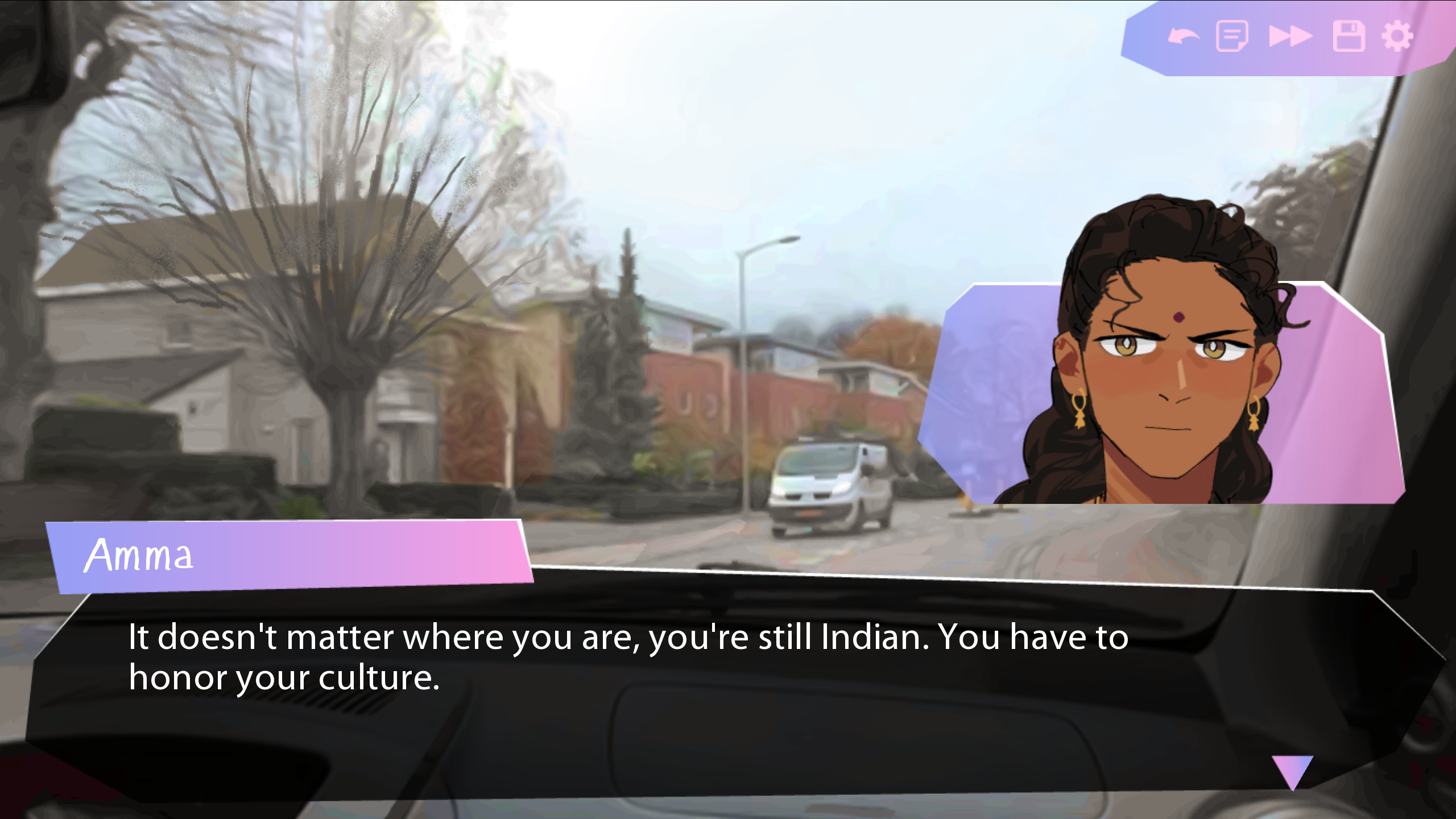

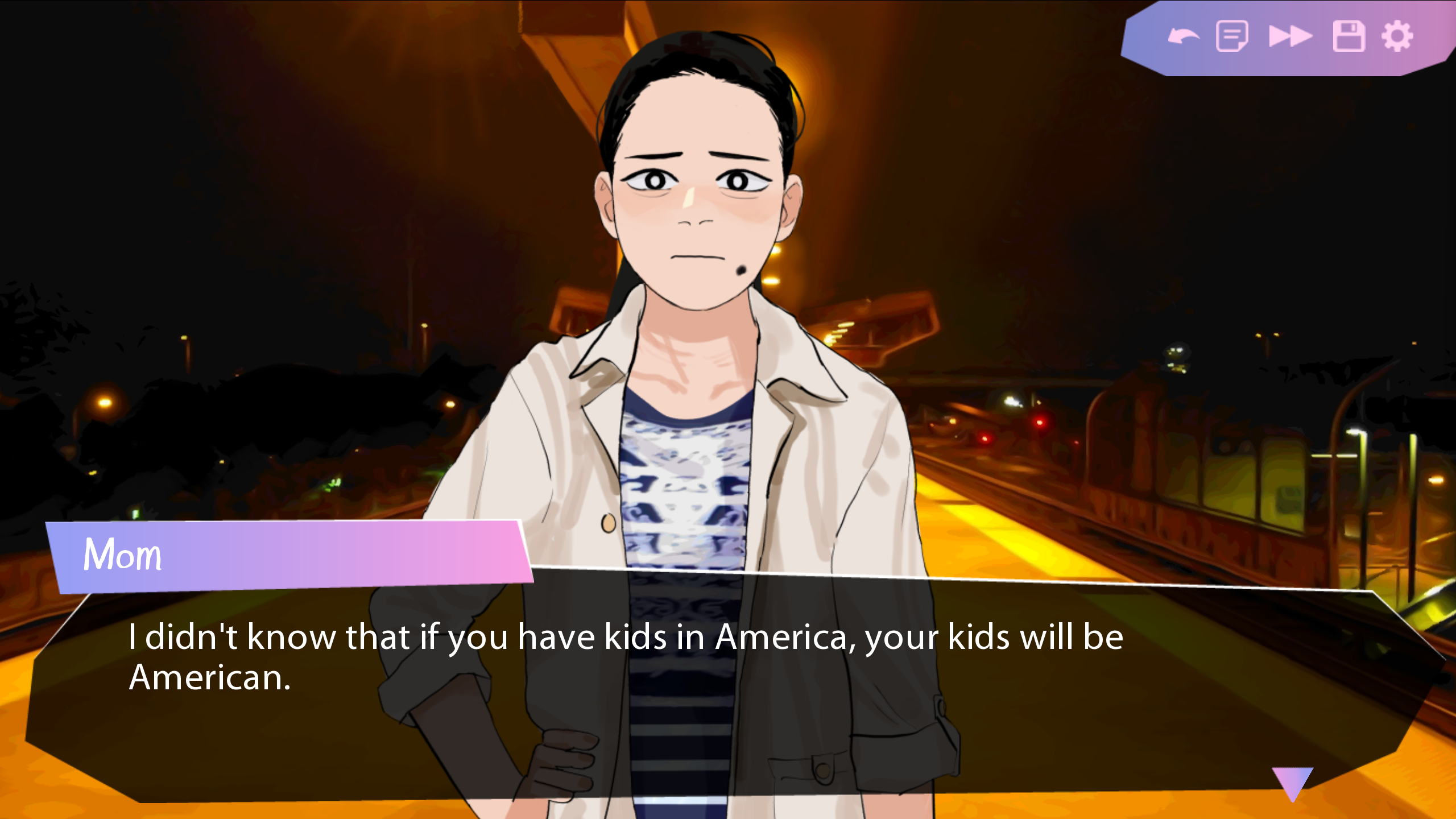

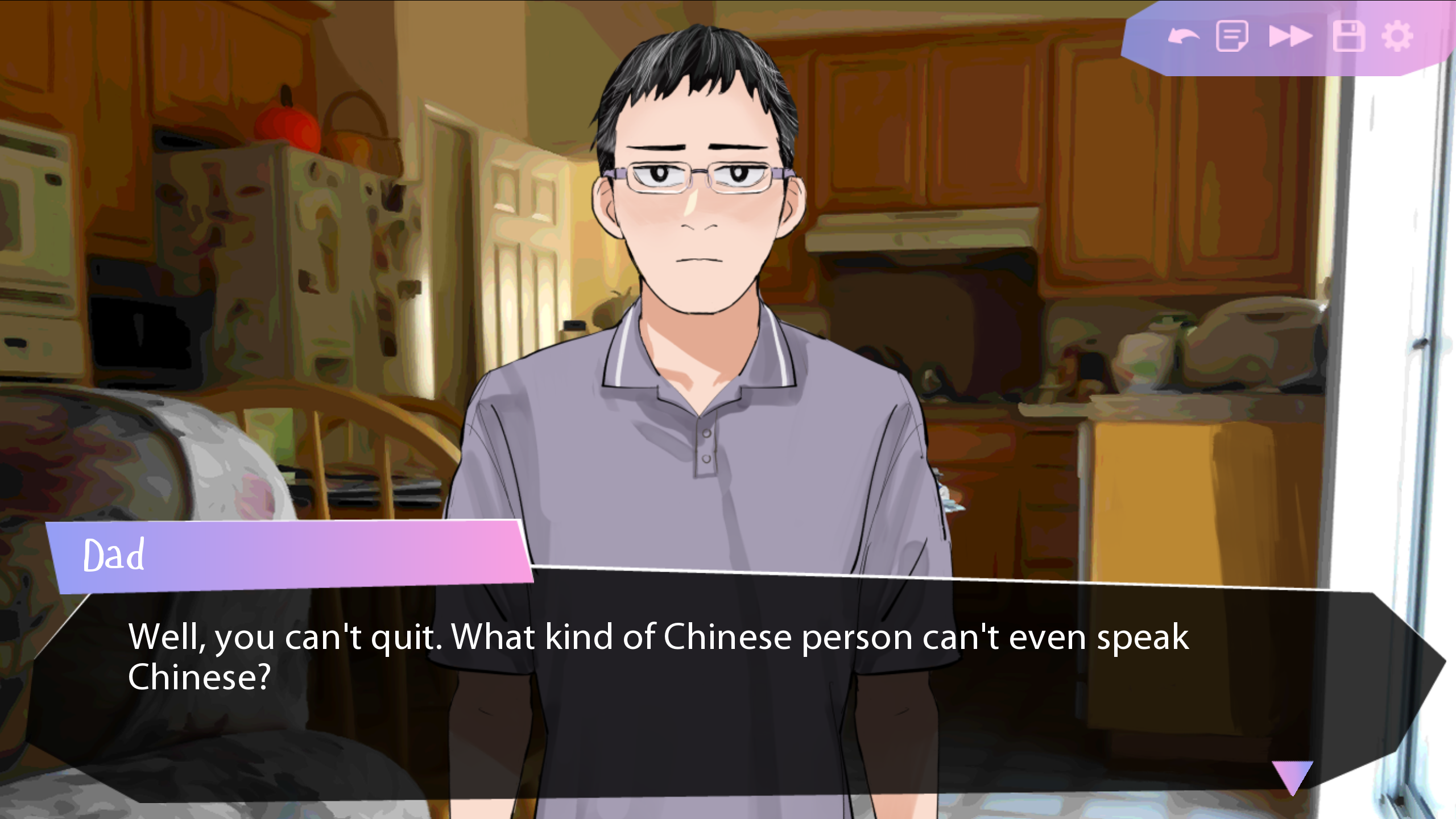

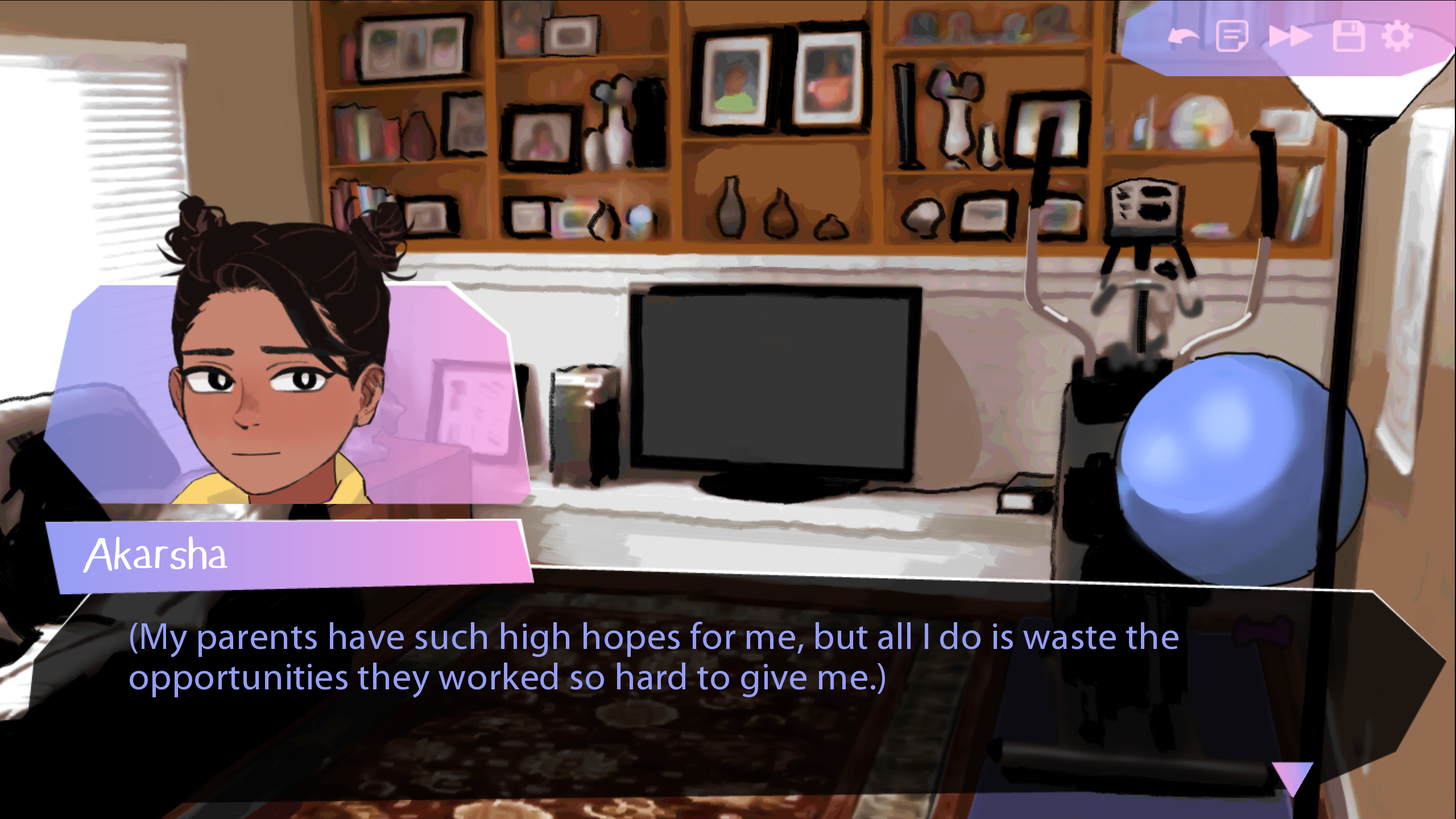

While we were there, I felt like a stranger despite the fact that for once, I was surrounded by people who looked exactly like me. People I should have been exactly the same as. But I constantly worried, could the native people walking the streets tell I was a foreigner? It felt obvious from the shuffling steps I took behind my dad as he led the way, and the sweat pouring from my eyeballs. My memories of the visit are mixed, and the only reminders I’ve kept of it are some photos taken during the trip. In the most precious photo I saved, my sister and I are sitting on either side of my grandparents, smiling to the camera. But I remember wanting to cry whilst we waited for my dad to take that picture. Despite them being family, grandparents that I respected and treasured, I couldn’t help but feel like they were strangers I would never understand. That was the last time I saw or spoke to my grandparents. And it’s also the reason why, as I sat playing Butterfly Soup 2 at midnight, I cried the tears Noelle, one of the game’s main characters, did not. Noelle is an American-born Chinese girl. Like most children of Chinese immigrants, she attended Chinese school when she was younger. She persuaded her parents to let her quit because she didn’t understand how it would ever be relevant, nor when she would ever need it. She is forced by her parents to pursue academic success, while they instil in her the instinct of competition. A familiar tale to many second-generation (and subsequent) Chinese immigrants, myself included. In the game’s final chapter, her parents take her on a rare trip to Taiwan to visit family. They visit the columbarium where the ashes of her 阿嬤 (Ah-ma, a Taiwanese term for grandma) are kept, and Noelle feels awkward. She doesn’t know how to communicate with her 阿公 (Ah-gong, grandpa), or what she would bring up in a conversation with him. As her cousin and mum tearfully offer their prayers to Buddha for Ah-ma, Noelle is struck by how little she knows about her family. Playing through this part, I didn’t feel like I was staring at my monitor watching a story. All of a sudden I was 19 again, stranded in the humidity of Hong Kong and suffocating under the weight of the realisation that back home, the white people never saw me as British, but in Hong Kong, I couldn’t call myself Chinese either. When Noelle speaks to her cousin Chun-hua after, she reaches a fundamental dilemma in understanding her identity - how do you bridge two separate cultures, which at times have nothing in common? Can you untangle history, culture and personality from your upbringing? “How much of my personality is just a product of being raised by an immigrant helicopter mother with no friends or family around to balance her out?” Noelle asks herself. If you’ve played either of the Butterfly Soup games, you’ll know that Lei is not shy of exploring topics so openly like this. What caught me off-guard was the topic itself - I had expected Noelle to begin questioning her sexuality in the second game. I hadn’t thought the struggles of younger generation immigrants would be laid bare alongside this. Lei ensures we see Noelle as a complex person. Lei shows how the separate strands of Noelle’s identity, whether that be cultural or sexual, cannot be separated, and the ways in which they interact are reflective of the experiences of second and subsequent generation immigrants. Despite feeling little to no connection to her Chinese ancestry, Noelle is still eager to connect with her parents. She strives for perfect grades, to attain the “better life” her parents wanted to give her in moving to America. In this, she believes her future plans should be “to secure a respectable job, marry a similarly successful man, and spawn two well-behaved children in the suburbs before I’m 30”. The textbook definition of the model minority, which certainly does not involve being in a queer relationship. Despite being desperate to throw away the Chinese part of her when she was younger, she’s still affected by it. It wasn’t just empathy I felt for Noelle. It was cathartic to experience a piece of media which depicted this struggle so openly. This was one of the reasons why Lei was keen to explore the subject, she told me over email. “There’s just not a ton of media out there about growing up as a queer Asian American girl! I feel like I grew up without knowing the words to describe what I was going through. I think that playing a game focusing on that specific combination of things would’ve helped me grapple with the unique mire I was entrenched in, so I set out to make one.” Lei likened the process of creating the story skeleton for the sequel to “untangling a lifetime’s worth of wires that were knotted together”. For Noelle’s narrative to come together as a whole, Lei had to deconstruct Noelle’s identity to understand each individual component and how it would affect the character. Lei does this brilliantly, presenting Noelle’s internal struggles in an honest way that is validating for second and subsequent generation immigrants, and informative for those who are less educated about these issues. The broader topics involved in the questions Noelle asks about her Chinese identity aren’t specific to East Asian immigrants. Lei also wanted South Asian players to relate to her characters as well. “Something that made representing both experiences easier,” she told me, “was how much overlap there is in the second generation immigrant experience, regardless of culture… The disconnect from her culture Noelle feels during her trip to Taiwan turned out to be relatable to a lot of South Asians, too.” There are further nuances to Lei’s representation of South Asian characters. One of the other main characters, Diya, receives a lecture from her mum to not date any BMWs - “no Blacks, Muslims, or Whites” - as it would be considered disrespectful in traditional Indian culture. Akarsha, another main character who is Indian, brings up how people outside of Indian culture misunderstand Desi identities. Again, second and subsequent generation immigrants of all cultures have similar experiences - the pressure to marry someone from the same culture, or how people outside our culture are ignorant to the complexities and history behind subgroups within our culture. The sincere respect with which Lei handles Asian representation is clear. She told me she drew on many of her own experiences when writing Butterfly Soup. The Asian-American enclave she grew up in became the setting for the game, and childhood conversations with her friends about their “complicated relationships” with their immigrant parents inspired the in-game dialogue. At one point in the game, Noelle tries to translate a poem her mum wrote. Lei spent two months teaching herself Chinese as research for this part of the game, and the results changed the direction of that part. Lei had originally wanted a positive ending, but said she felt “defeated while doing [her] own studies that it would’ve been completely insincere”, so she changed the end of the scene to reflect the experience. Lei also read books by Asian authors, and cited No Straight Thing Was Ever Made by Urvashi Bahuguna, a collection of essays on Bahuguna’s journey with mental health as an Indian person. Butterfly Soup 2’s final lines quote Immanuel Kant, and Lei learnt of the quote through No Straight Thing Was Ever Made. “I actually picked the book up assuming the “straight” in its title was in reference to one’s sexual orientation,” she admitted, “and when I realised that it wasn’t, I decided to add that double-meaning to the quote in my game.” The original Butterfly Soup released in 2017. In the five years since then, the political climate has changed vastly and so I was curious to know if global events (namely Covid and the increased awareness of anti-Asian racism) changed Lei’s direction for the game. It was the Asian-American response to anti-Asian racism that affected Lei the most, she told me. Her frustration at the “Asian Lives Matter” and “Stop Asian Hate” campaigns, which she felt were “cartoonish oversimplifications” and lazy attempts to piggyback off the progress made by the Black Lives Matter movement, had a larger impact than the racism itself. “I felt like many of my Asian-American peers grew up without developing any understanding of their place in the world and in history beyond liking boba. I think that helped motivate me to finish the game in hopes that the story might trigger some introspection in people.” So what’s Lei got planned next? Lei told me she has some ideas for another Butterfly Soup game, but wants to branch out into different genres first. Lei hadn’t expected the first game to receive as much attention as it did, but the pressure of meeting fan expectations while remaining true to her own vision made her feel “terrified” about reception to the sequel. “The more I worked on it, the more I started telling my friends I’m never making a sequel again”, she recalled. Currently, she has an Asian fantasy mystery game inspired by Disco Elysium and AI: The Somnium Files in development (which sounds absolutely fantastic). “Maybe time will help me forget my conviction to never make a sequel again!” At the same time, Lei hopes to see more progress within the games industry on Asian representation. “I wish people would hire more Asian people to write Asian characters,” she said, “instead of writing what are essentially white characters wearing Asian skins.” Lei proves in Butterfly Soup 2 that authentic and impactful representation can be achieved in games with frank conversations about Asian identity. If one solo indie developer can do it, why can’t triple-A studios do it too? We’ve seen indies and mid-budget games make progress. Prey 2017’s Morgan Yu is a personal standout for me. But Asian representation within the triple-A sphere is yet to make any substantial ground. 24 years after her first appearance in the Resident Evil series, people are still surprised to learn that Ada Wong is Chinese, and it pains me to say this, but I can understand why. Like Lei said, she’s just a white character wearing an Asian skin. In Resident Evil 4, the only evidence of her Chinese heritage is the traditional cheongsam (長衫) she wears, which has been conveniently altered to be more “sexy”. Hell, in Resident Evil: Retribution, the only one of Paul Anderson’s live-action movie series which Ada appears in, she was played by Chinese actress Li Bingbing, only to then be dubbed over by Sally Cahill. We aren’t just a skin for writers to slip over their characters to masquerade in. We are complex people, with our own internal struggles, and I wish the video game industry would stop glossing over that fact.