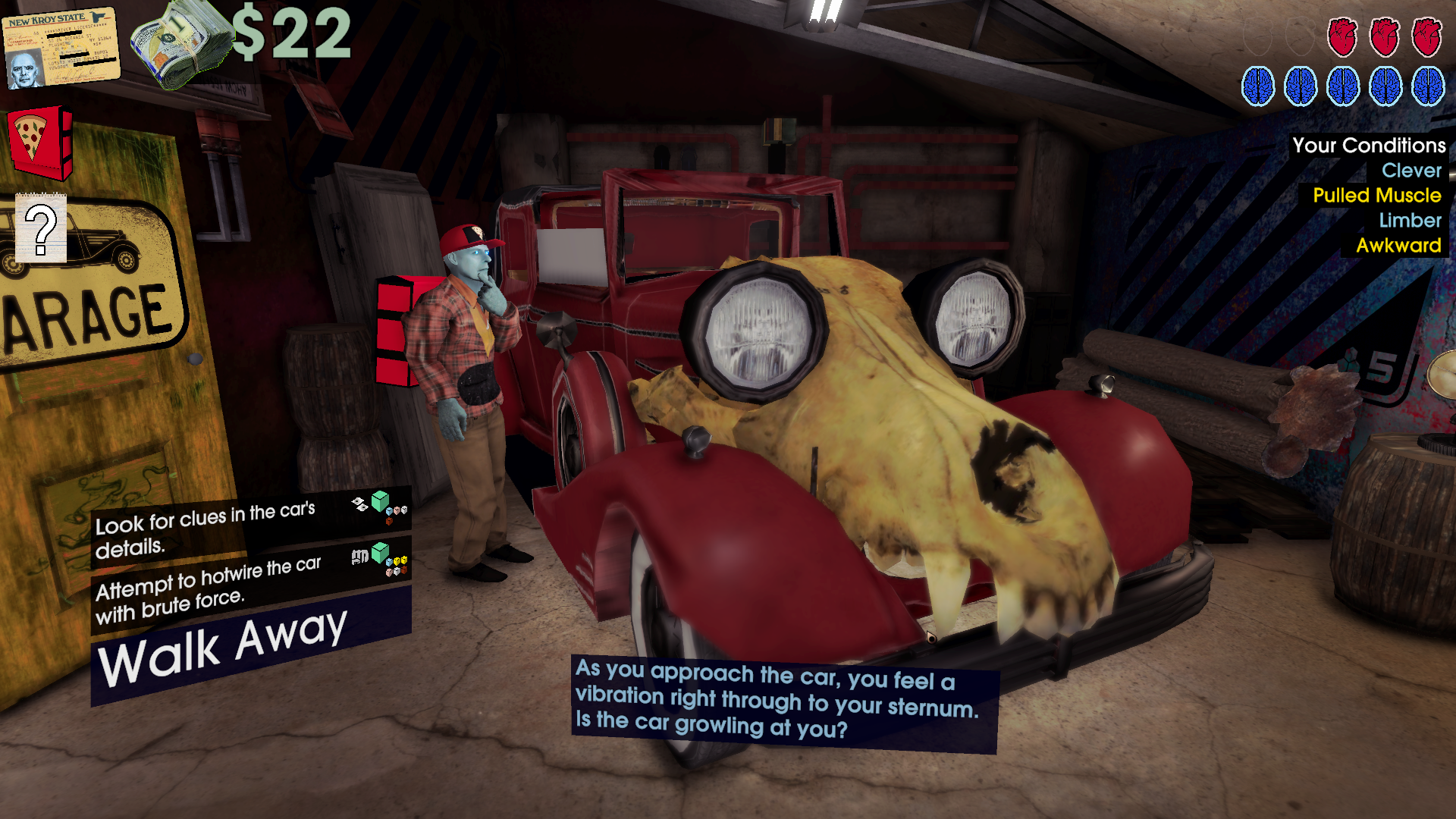

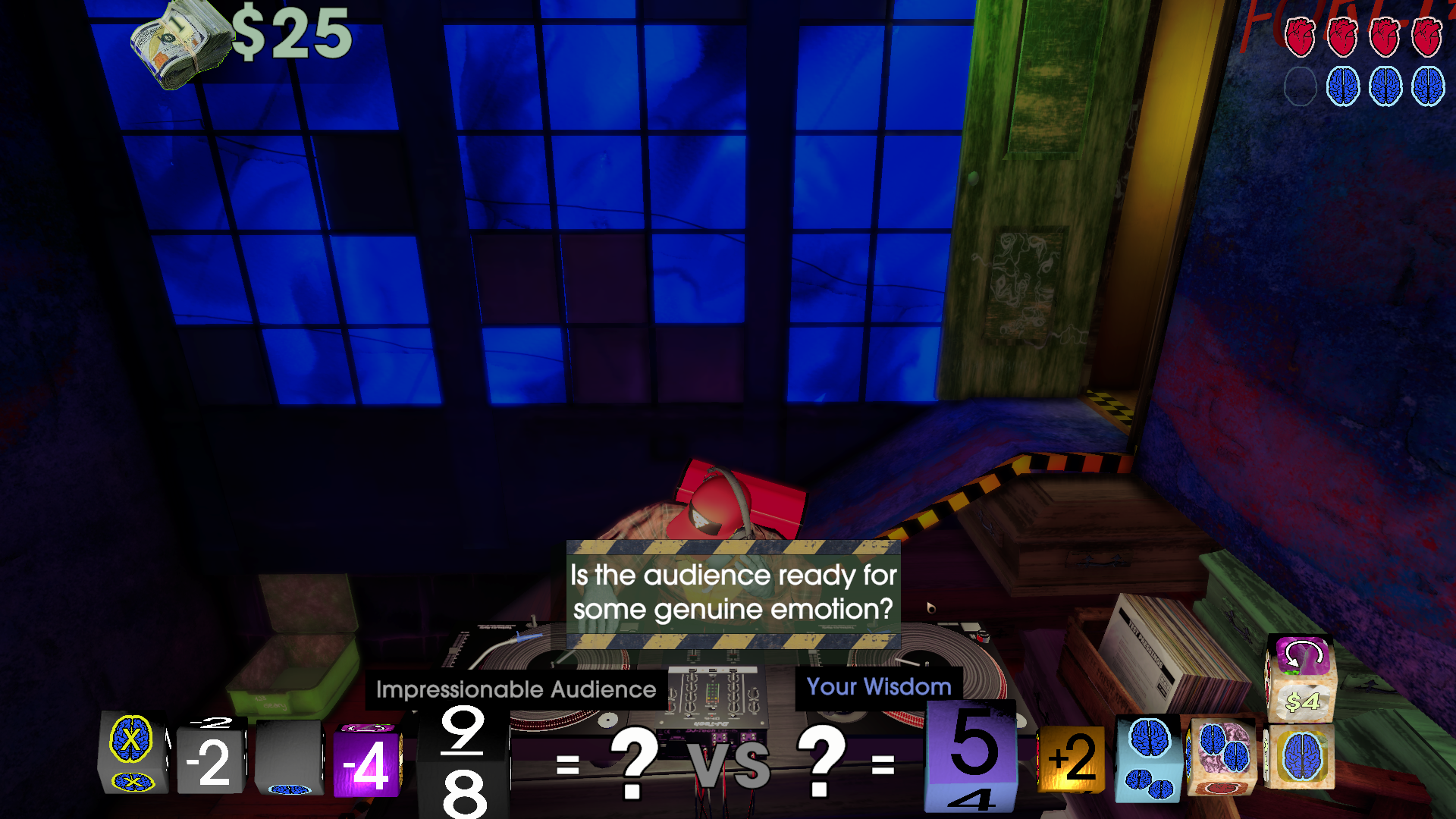

The brain behind the Off-Peak universe is composer/musician and game designer Cosmo D, who makes brilliantly eccentric narrative adventures that revolve around music, performance, and good old fashioned capitalism. The games can be enjoyed individually, but they’re all cohesive branches of a much bigger and weirder tree; The Norwood Suite (2017) remains a personal favorite for the way it marries the mundane with Off-Peak’s tantalizing mythology, and Betrayal at Club Low is tonally and thematically no different. But as a narrative-driven dice game (the first time the Off-Peak world has embraced such a drastically different mechanic) Cosmo D has sagely tapped into the insatiable lizard brain of my long-dormant inner club kid – after my first playthrough I’m riding the invincible high of a successful night out, and immediately want more. I play a humble pizzaiolo-spy who works for The Circus, an enigmatic intelligence agency. In this world, pizza is a cultural cornerstone that commands serious respect and craftsmanship. My acerbic handler Murial appears with a mission: infiltrate Club Low and rescue a fellow agent from a local thug, Big Mo, who appeared in 2020’s Tales From Off-Peak City. Betrayal continues Tales’ secret-operative-as-pizzaiolo thread, but where previous games were structured more like exploratory point-and-click vignettes, this one is more of a study in strategy and social engineering. Tonight, it’s all about cooking “pizza dice” with different toppings at conveniently placed ovens. Some toppings are multipliers that increase the amount of tips I get from giving out pizza, some replenish my energy and nerve bars, and others manipulate my opponent’s dice. Cash goes toward bolstering skills like Observation, Wisdom, and Wit, which are reflected in my skill dice. The dice are my only friends in a club full of people with their own private agendas. I realize, on my second run, that the game leans toward Deception, Physique, and Music as the most useful skills, at least on the “Typical Thursday” and “Wild Night Out” difficulties. Every action involves skill dice and condition dice. For instance, dumpster diving using Observation triggers a roll for the distinctly unhelpful condition “Smelling Like The City,” which will adversely affect my next roll. A failed roll may incur “Thrown-Off” – a nerve debuff that can be a death sentence if I’m already low on nerve. I might end up bolstering my opponent by making them suspicious. Nailing the right conditions, like Clever or Zoned In, can help me overcome an otherwise formidable foe. (Overall, the dice stuff is pretty intuitive if you’ve played enough dicey board/video games.) How Betrayal at Club Low transcends into another dimension lies in what I can only describe as psychological witchcraft on the part of Cosmo D, who, as a musician, knows exactly how to work a crowd (or in this case, work a player). My options for getting into the club evoke a full spectrum of relatable public anxieties, from cutting the line to buttering up the doorman. Whomst among us hasn’t attempted to weasel their way into a place that they shouldn’t be? Furthermore, it’s not just an average night at Club Low – the extremely popular DJ Chad Blueprint (heir to The Norwood Suite’s legendary DJ Bogart) is behind the decks, and people are itching to get in. There’s all sorts of delightful personal baggage that comes into play – I’m an awful dancer, so it was somewhat gratifying to use my dancing to make people so uncomfortable that they were willing to avoid me entirely (which of course also triggered a raft of cringey personal memories about late 90s/00s club nights). This is very much a game about gambling with endorphins and the endless euphoria of getting away with shenanigans, which vibes perfectly with the essence of dice games. It reminds me not just of clownish things I used to do to sneak into console areas or VIP sections, but the sense of invincibility embodied in slacker-hustle movies like Doug Liman’s excellent club/crime caper, Go, which came out in 1999 with an equally iconic soundtrack. Even when things went so horribly wrong, there was always the possibility of something going right. Bouncing back from gaffes and mistakes is one of the most redemptive tropes in a social club setting, when the awkward outlier finally gets their moment in the proverbial sun (of course, we never see the light of day in these strictly nocturnal games). This is to say, there will always be a Chad Blueprint, but armed with the right knowledge and skills, even a pizzaiolo like myself can unseat him. Club Low itself is a beautiful microcosm of entertainment capitalism, which continues Cosmo D’s long tradition of poking at the material costs of making a living. This isn’t just about the business of having “fun,” but an entire subclass of people who live to work at night, who take multiple jobs, and work behind the scenes to prop up an institution like Club Low. There’s a whole zoo of characters engaged in various scenarios that touch on real-life problems – piracy and bootlegging, unscrupulous business contracts, moonlighting, an absence of fair labor practices are just a few. The chef is worried about her flamingo stew – it needs to be worthy of Big Mo’s discerning palate – as well as health code violations; the manager, Kathleen, exhibits classic landlord brainrot as she ponders anti-labor measures to get the most value out of her underlings. It’s amusing that given how much trouble I’ve gone to get into Club Low, it turns out that most of the staff just want to leave and hang out with their own friends somewhere else. But really where everything comes together, as it should, is on Club Low’s miniscule dancefloor, where I make valiant attempts to become one with the animal of the crowd (one of those instances where Physique and Music really come in handy). Cosmo D soundtracks always deliver, and this one is no exception – even through a screen, the sense of communal intimacy and telepathy through Cosmo D’s vision of dance is infinitely more powerful than watching an early Boiler Room set. The game’s chaotic momentum syncs perfectly with every beat, like a sentient undercurrent of sonic motivation that reminds me to keep pushing along. If I conquer the dancefloor and win over my fellow dancers, it leads to arguably one of the most triumphant moments in the game. Surfing on my success, I decided to tackle the hardest difficulty in 4am mode, which imbues the NPCs with random unpredictable behaviors. Normally I wouldn’t torture myself like this, but I’m hooked. The game suggests that I go in with a plan, but I throw caution to the wind and continue distributing my skill points and making decisions impulsively. Making money is hard, and every condition is a potential landmine. I also only have a tiny amount of energy and nerve – 3 of each – which means any hazardous condition (say, a roll that inflicts -4 nerve) could spell my doom. Progress is incremental, and energy suddenly becomes much more of an issue than in previous games. Any debuff roll from my opponent can one-shot me into oblivion. I lap it all up like a masochist – this is clubbing at its most demented. Betrayal at Club Low is already one of my favorite games this year, and one of my favorite Cosmo D games to date. There’s something strangely comforting about seeing the distinctive Off-Peak monuments and architecture, like seeing an old friend who’s managed to pick up some delightful new tricks. My next personal challenge is to try the Iron Pizza mode – sort of an equivalent to permadeath where I only get one save file, where I’ll definitely have to put a bit more thought into strategy and skill distribution. But in my own grand tradition of idiotic spontaneity when it comes to the art of going out – well, at least when I used to go out – where would the fun be in that?