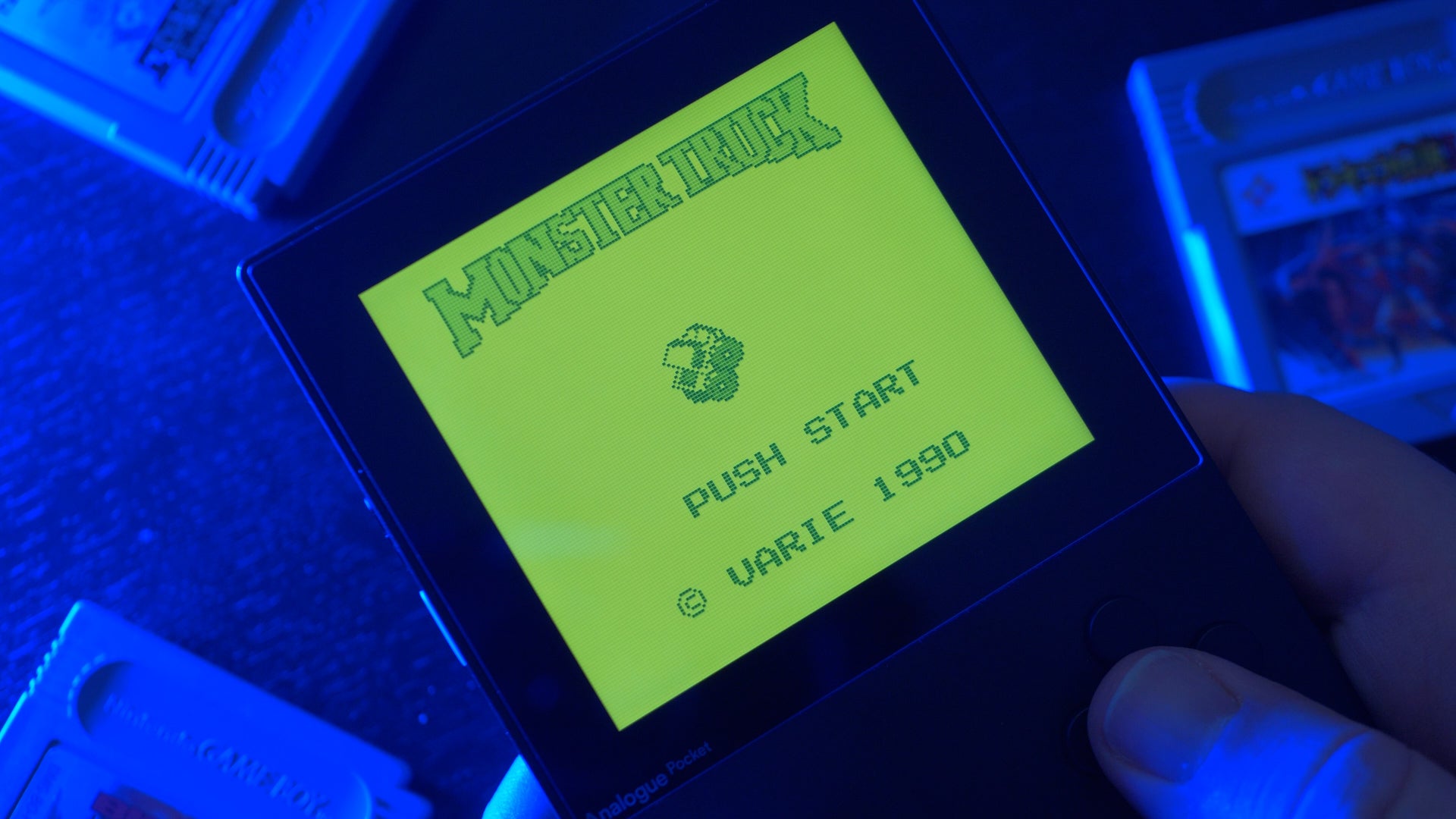

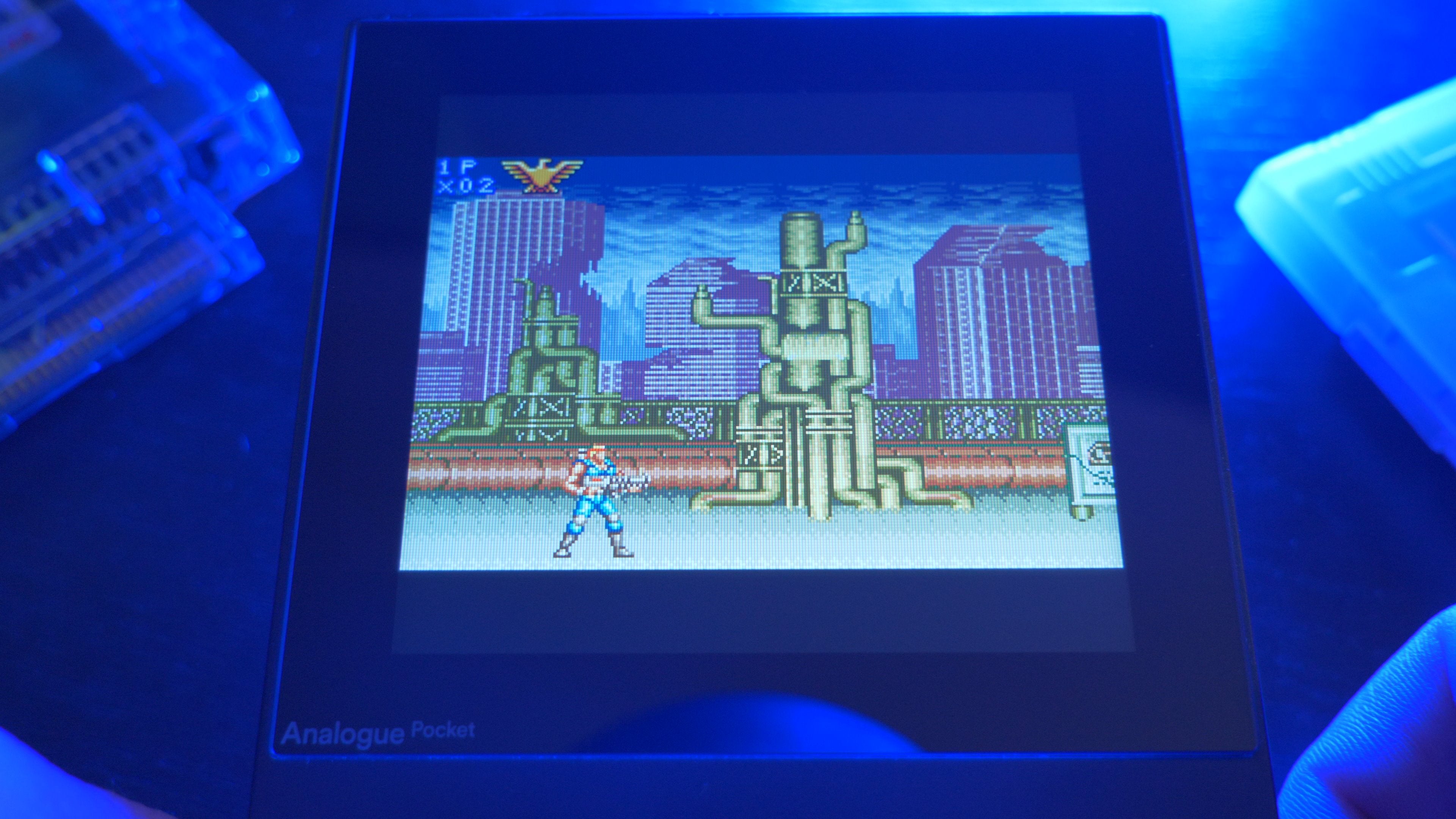

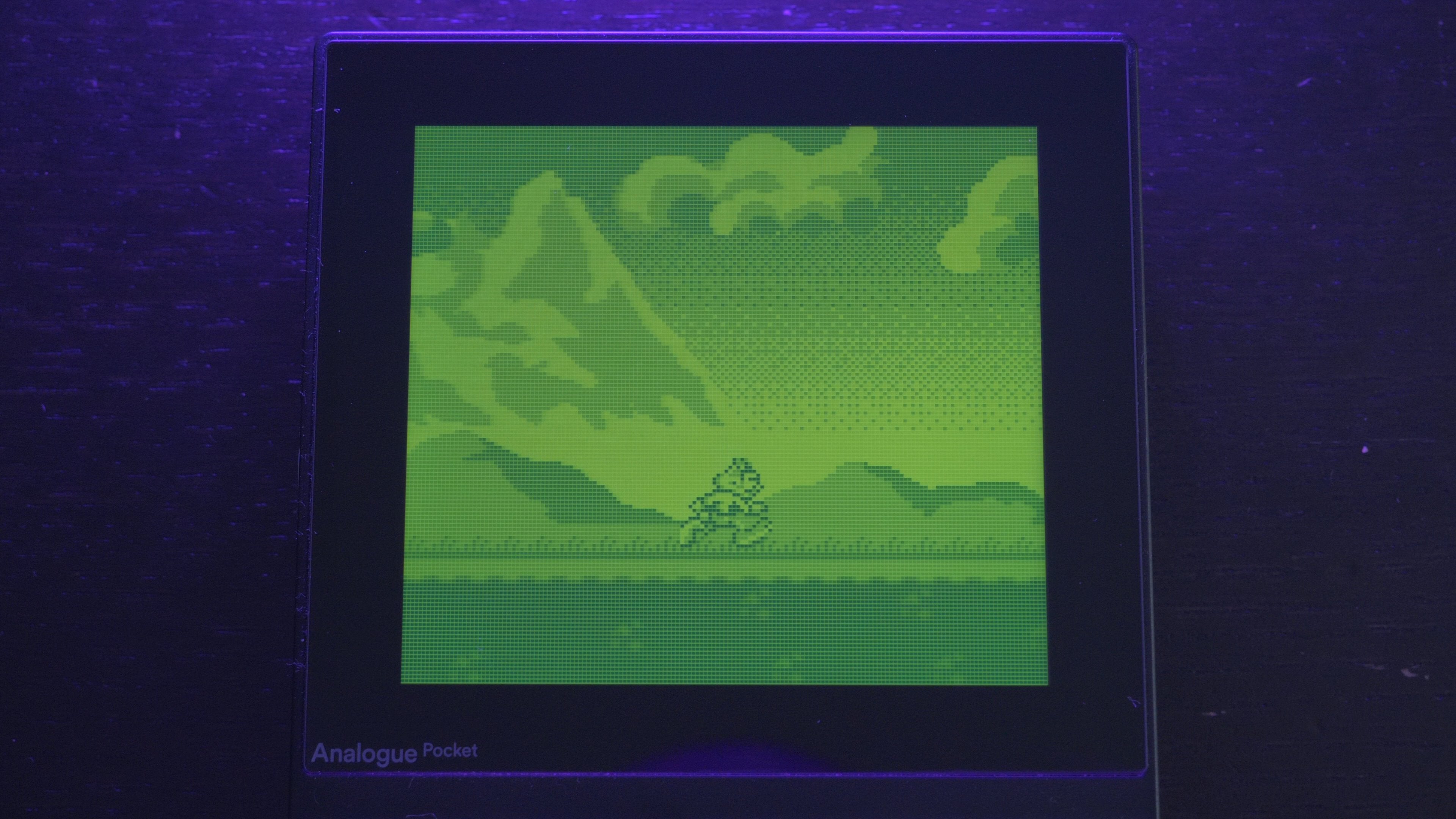

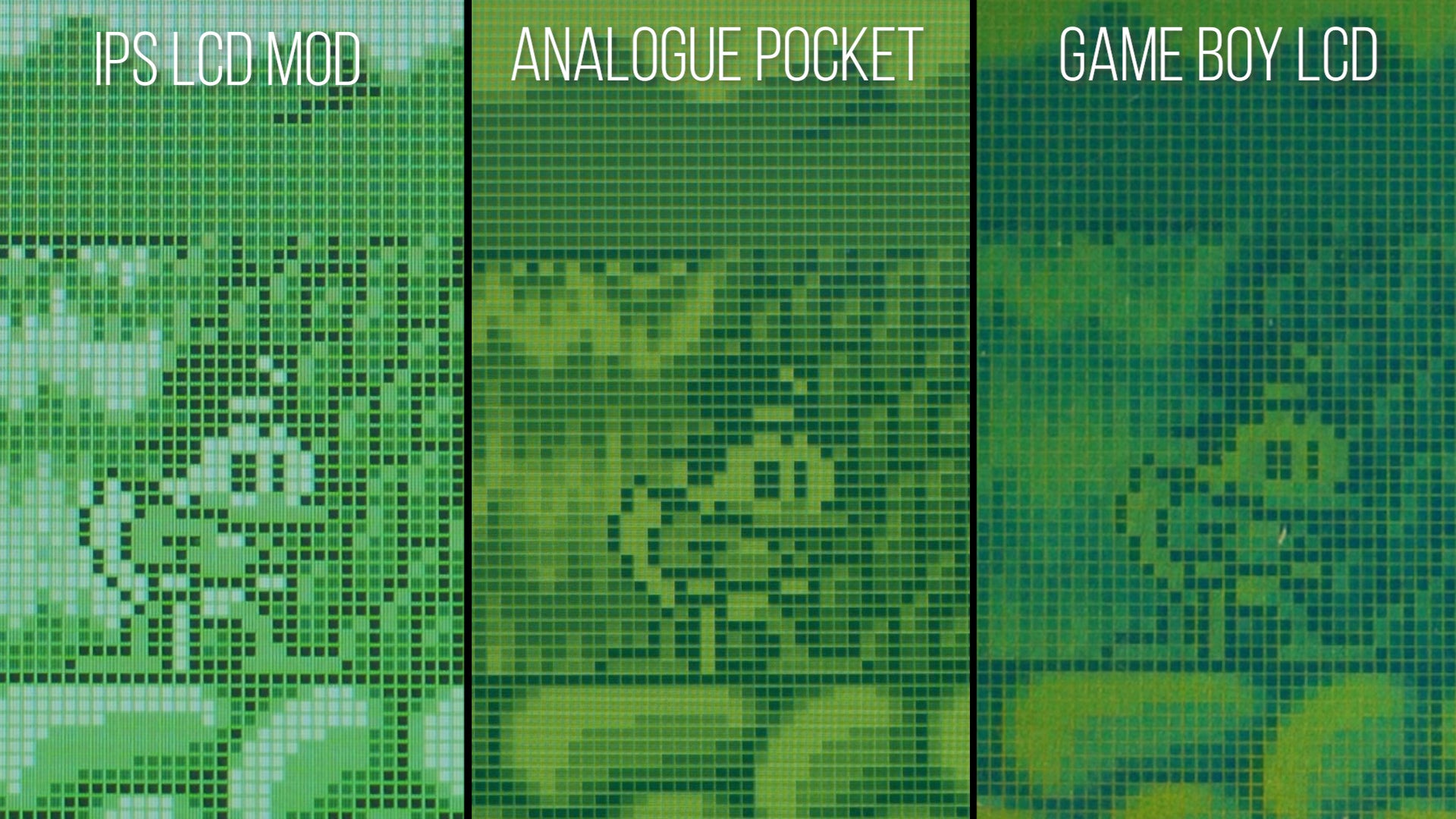

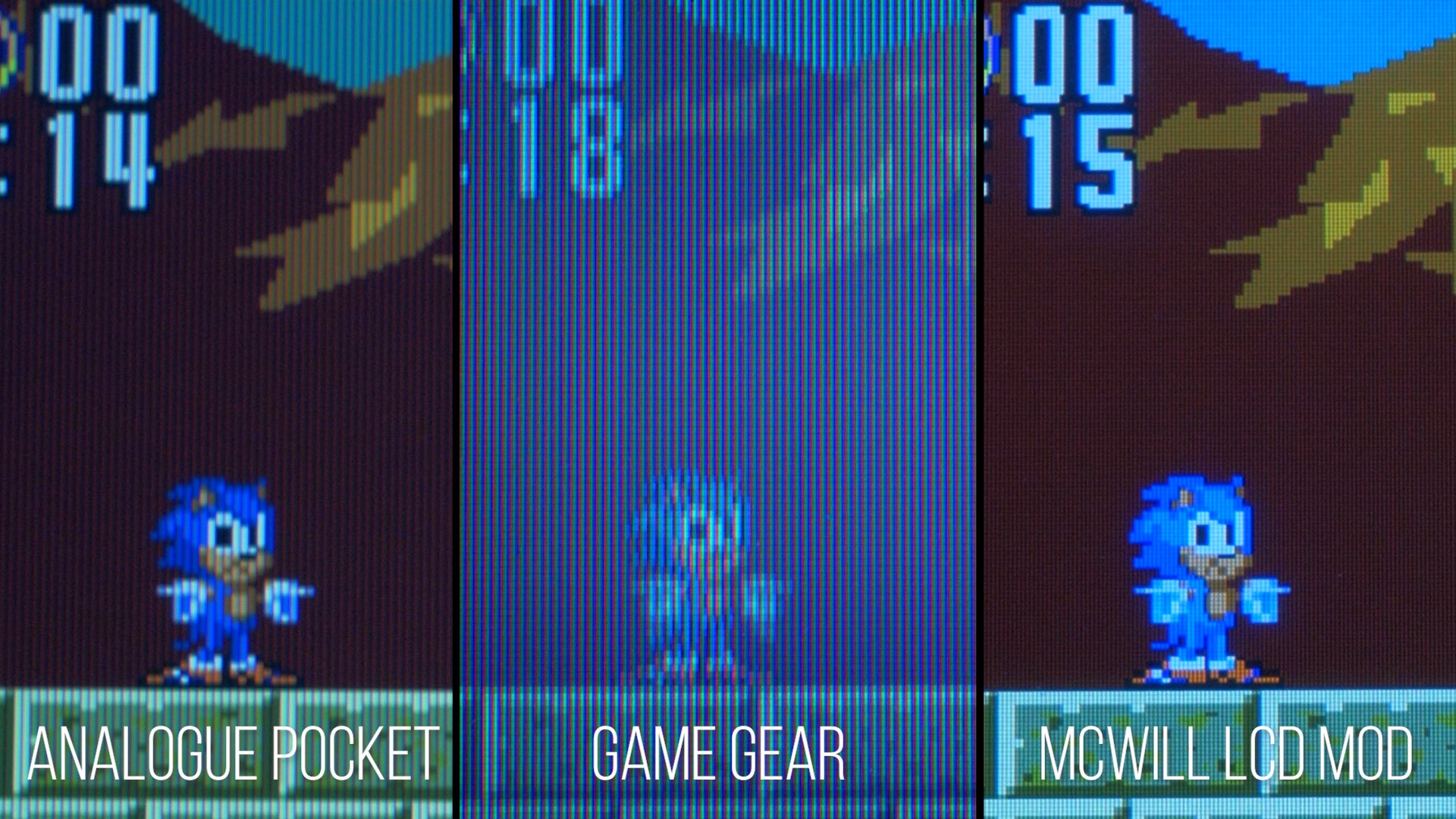

There’s no denying that the Analogue Pocket is a beautiful device - precise lines, subtly rounded corners and a beautiful Gorilla Glass screen lens impress when you first pick up the unit. It instantly feels premium in a way that exceeds anything Analogue has done in the past and this is important because, unlike, say, the Mega Sg, you’ll be holding the Pocket in your hands most of the time. The unit feels solid yet reasonably light - the face buttons are configured in the traditional diamond shape while start and select buttons rest near the bottom, straddling the menu button, which has multiple uses in this case. The d-pad is always a challenge as it’s crucial to the feel of the system. In this case, it’s pretty good. I’d say it’s slightly better than the d-pad functionality on a modded Game Boy. Just like those systems, however, diagonals can be slightly problematic in specific games but, by and large, it’s solid. Around the back, you have two shoulder buttons for Game Boy Advance games and a moderately exposed cartridge slot. This is an interesting design choice as it suggests that carts might wobble without the additional support brace provided by original hardware but it’s remarkably solid - plus you get to see the beautiful label artwork adorning many games. By default, it accepts cartridges for Game Boy, Game Boy Color and Game Boy Advance. As of this review, an adapter for Sega Game Gear games is also available with support for Neo Geo Pocket Color, Atari Lynx and more promised next year. The unit charges via USB-C, features a 3.5mm minijack output for headphones, a micro-SD card slot and includes a Game Boy style link-cable connector which allows you to play multiplayer games - even with original Game Boy Color and Advance hardware. The main and most important feature lies in the screen and the screen simulation modes available but to understand this we need to look back at original hardware. The original Game Boy uses a screen with a pixel resolution of 160x144, but the arrangement is interesting, with a spaced grid separating each pixel. It’s a very specific look and such characteristics apply to other portable systems as well. It’s an important point to make because the art used in these games was created specifically for these original resolutions and panels. When blown up in an emulator or displayed on a higher resolution screen, you’re left with a chunky looking experience that doesn’t quite look or feel right. Modders have built solutions to handle this, however, with LCD replacements featuring what’s sometimes called the ‘retro pixel grid’ which simulates the blank space between pixels. They look excellent but the look still isn’t 100 percent there. All of which presents a conundrum: the original screens on older handhelds are generally of poor quality and we do not want to replicate the ghosting or low visibility but we do want to emulate the reproduction of colour and the pixel structure. And that’s what the Analogue Pocket does, delivering screen modes that simulate the look of the original screens. With the Game Boy, for example, there is a visible border between pixels but there’s also subtle color information within the pixels, designed to more closely simulate the physical characteristics of a real Game Boy screen. The difference here is that it’s fully backlit and doesn’t exhibit serious blurring in motion. In addition, you have access to other modes, including one simulating the look of a Game Boy Light’s indiglo screen. Honestly, perhaps the most impressive filter is that which is used for Sega’s Game Gear - this is a tricky system that I feel is not usually well rendered either via emulation or replacement screens. The resolution is 160x144, like Game Boy, but with a wider aspect ratio meaning wider pixels. The original screens are very difficult to see and use these days and none of the replacement screens offer such a configuration and, as a result, you’re subject to scaling issues. Releases of Game Gear games elsewhere also tend to fall short. The Analogue Pocket, however, delivers a remarkably accurate Game Gear experience but without the flaws of the original panel. It’s genuinely striking to behold. The Game Boy Color screen simulation also looks great in action, simulating the pixels of the system while modifying the colour saturation to suit the content. Game Boy Advance? This one is trickier as the original hardware doesn’t scale evenly to the Pocket’s native 1600x1440 screen and as a result, there are some repeating patterns visible on solid colors when using this mode. I would say it’s a minor thing overall and not an issue for most games but it’s not quite as successful as the other systems. There is an alternative option though - an Analogue mode that basically displays the game in a raw pixel mode, opening up a number of additional scaling options - but I’m not a huge fan of this specific mode, which presents rather like a standard emulator as opposed to a faithful recreation of the original display. The reason why the screen works so well is that the Pocket uses a very high-resolution LTPS panel with 615 pixels per inch. LTPS technology is top tier when it comes to LCD production - it’s efficient, it allows for densely packed pixel grids and it produces faster motion response and deeper black levels. The big draw here is that Analogue selected such a high-quality panel with a desirable aspect ratio - a problem facing so many other portable devices made for retro gaming today. Due to the high-resolution, there’s more than enough pixels to simulate the characteristics of individual pixels such as those found in the Game Boy. It also allows for a perfect 10x scale: 160 becomes 1600 and 144 becomes 1440 - the screen, therefore, is 1600x1440. It’s also possible to fine-tune the experience by adjusting saturation and sharpness - essential as the original screens could never display super-rich colours. There are also some other neat options such as the frame blending feature. This does not simply add artificial ghosting to the mix, rather, it’s used in cases where flicker occurs. Yes, original Game Boy developers actually leaned into the deficiencies of the display to produce some interesting effects. Rapidly flickering content on a panel renowned for its LCD ghosting could simulate transparency, very useful for water, clouds and other effects. With frame blending disabled, you’ll see this flicker as a result of the faster panel response. Enable it, however, and the system blends these two frames together to create a solid object that still retains the intended effect. Ultimately, the Pocket’s display is exceptional. No other clone device or aftermarket screen mod comes close to the quality of this panel - and I feel it’s an example of what’s possible with a sizeable budget for such a product, combined with an approach that zeroes in on authenticity. Most of the screen mods or emulation-based handhelds are limited by screen selection - it’s expensive and difficult to source a screen like the one used in the Pocket but I feel that’s a huge part of the experience. Is it perfect? Not quite. Persistence blur inherent in LCD technology creates some artefacts and although light years beyond original hardware, we’re bumping up against the limitations of sample and hold LCD technology. Beyond screen quality, the Pocket also has stereo speakers built into the sides of the unit that can be cranked up to a surprisingly high volume. The speakers sound excellent allowing much higher fidelity sound than any of the original systems. What I really want to mention, however, is the enhanced audio feature available for Game Boy Advance. You see, by default, I find that Game Boy Advance games tend to exhibit scratchy audio when using sample-based playback. The higher quality option here basically solves this by applying filters in such a way that audio quality is hugely cleaned up. The last major hardware feature that deserves a mention is the sleep mode. Press the green button during play and the Pocket goes to sleep, keeping your progress in the process. Why is this a big deal? Simple - it works with original cartridges in a way that the classic consoles could not. The Pocket uses a live cartridge bus that behaves much like the real deal so the fact that this works as well as it does is really cool. But there’s a caveat - it only works with legitimate carts. The Everdrive (a cart replacement that runs ROMs from SD card) does not currently allow for sleep mode, instead asking you to power down. Actual save states are also possible but this feature is currently in beta and these states are temporary - disappearing when you change games. According to Analogue, more complete support is coming when Analogue OS receives its major update. Still, between this and sleep mode, there is a lot of additional convenience here when playing portable games. So, in terms of the hardware, the Analogue Pocket is a home run. I should touch quickly on battery life, though. I don’t think there’ll be too many concerns here. The Pocket features a 4300mAh lithium-ion battery, with one charge being all I required to complete an entire day’s worth of b-roll filming. However, there’s also an option to utilise the Pocket on an external display and that is where the Dock comes into play. This is a sturdy device, offering two USB-A ports, a USB-C port for power and an HDMI output. Simply place the Pocket into the docket and you’re playing on your TV. However, right now, while the hardware is sorted, the experience itself is still far from complete. Analogue tells us that an upcoming firmware update will add many additional features to the Dock including the option to utilise Analogue’s DAC for use with CRT displays - something I’m personally looking forward to - but in its current state, it’s basic. Firstly, the display options themselves are limited, with none of the advanced screen modes from portable mode available when docked. Given the option for 480p, 720p and 1080p output, I wouldn’t expect them to be able to duplicate this perfectly due to fewer available pixels, but I’d like to see this improve as Game Boy games in particular benefit greatly from this. Instead, you have access to a handful of palette options - they’re fine on their own with pleasing colours but it’s not quite what I had hoped. It’s more comparable to what you get from, say, the Super Game Boy or Game Boy Player. That extends to other elements such as colour saturation - this is not available in Docked mode which means, especially for systems with color displays, that the TV output produces overly saturated colours that feel less authentic. Then there are the scaling options. Scaling isn’t available if you’re using any of the pixel modes in handheld play - the options are greyed out. So, first you need to switch over to the default display mode before placing it on the dock. From there, you can manually scale the image to your liking. You can also pair Bluetooth controllers with the dock such as those from 8bitdo or other such as the Switch Pro or PS4 controller, but ultimately there’s the sense that while useful, the Dock doesn’t have the same level of functionality or attention to detail as the unit itself. Essentially, it’s a work-in-progress that requires key feature updates in order to shine. Beyond the hardware, it’s all about the accuracy of the FPGA cores. The Analogue Pocket may well be the first fully integrated FPGA-based handheld, but that does not mean that the recreation of the original hardware is guaranteed to be flawless. When testing a device like this, it’s all about seeing how the hardware copies with edge cases: games that push the original hardware in unique ways that can trip up inaccurate emulators and FPGA cores. There’s no way to test every game here for a review but if it can run these problematic games, that’s a good sign of accuracy. You can see my full test suite in the video at the top of this page, but suffice to say, that the Pocket is almost perfect, even working well with cutting-edge scene demos. Only homebrew DX conversions of Super Mario Land 2 and Metroid II fell a little short, exhibiting tile colour problems when played on the Pocket using an Everdrive. That said, visible glitches are present on real hardware as well, just presenting differently. Overall, compatibility and accuracy here is first class. Wrapping up then, the Analogue Pocket is the real deal. I’ve reviewed and played many modern products targeting retro games including software emulation devices, FPGA-powered hardware and mods for original consoles. The Analogue Pocket stands as my new preferred solution for playing the entirety of the Game Boy and Game Gear library. There’s really nothing better on the market right now. What about the future? In its current state, the OS is still lacking key features, due some time next year. These features are very interesting indeed and potentially game-changing because there’s actually a second FPGA chip in the console, allowing developers to create new cores for other systems. More adapters and improved dock support are also coming soon. However, even without these features, the Pocket is a phenomenal achievement. It’s exactly what I’ve been wanting for years, especially when it comes to screen quality, where mods and other systems fall dramatically short. The price is eminently reasonable too for a project of this quality - shipping at $219, with a new wave of pre-orders opening up today.